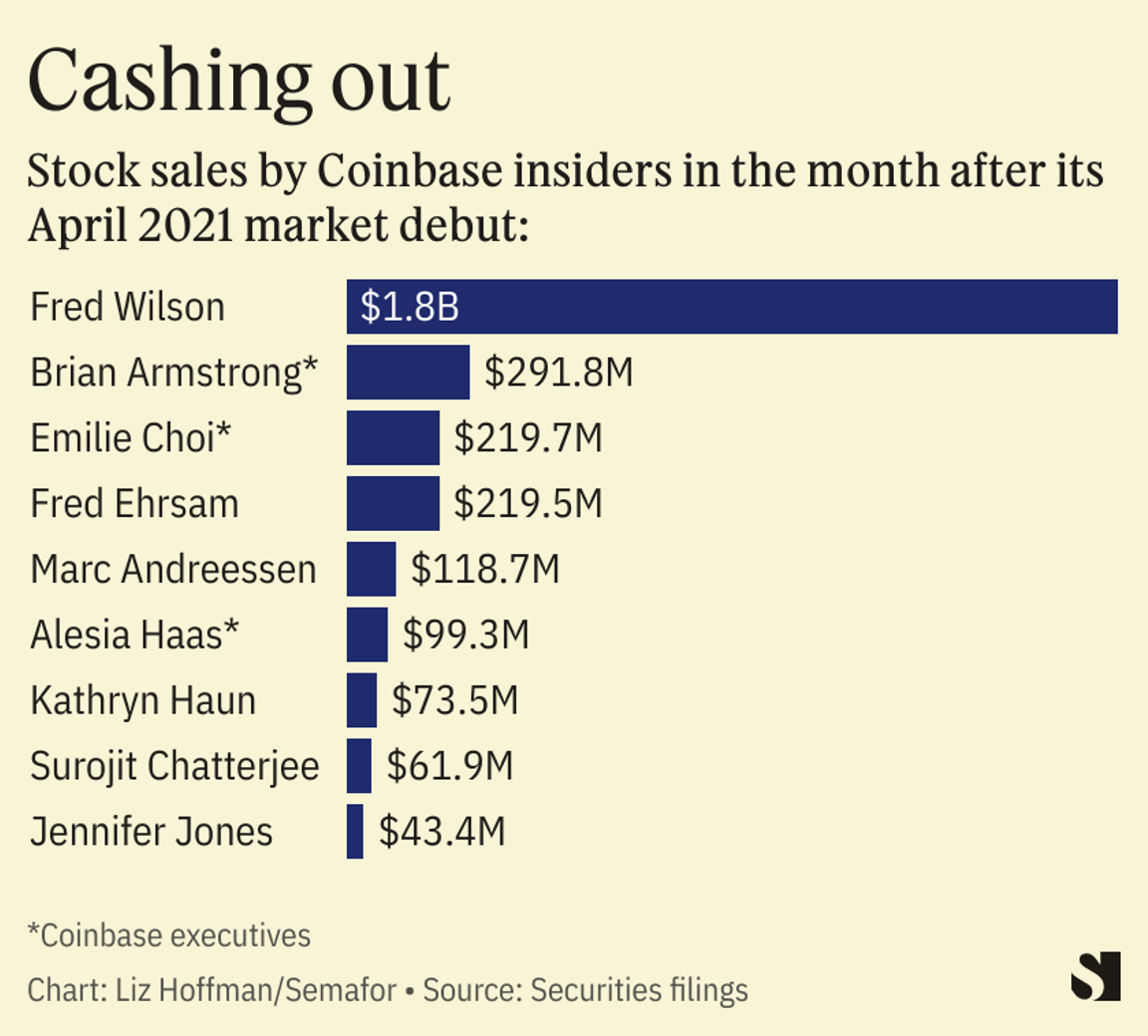

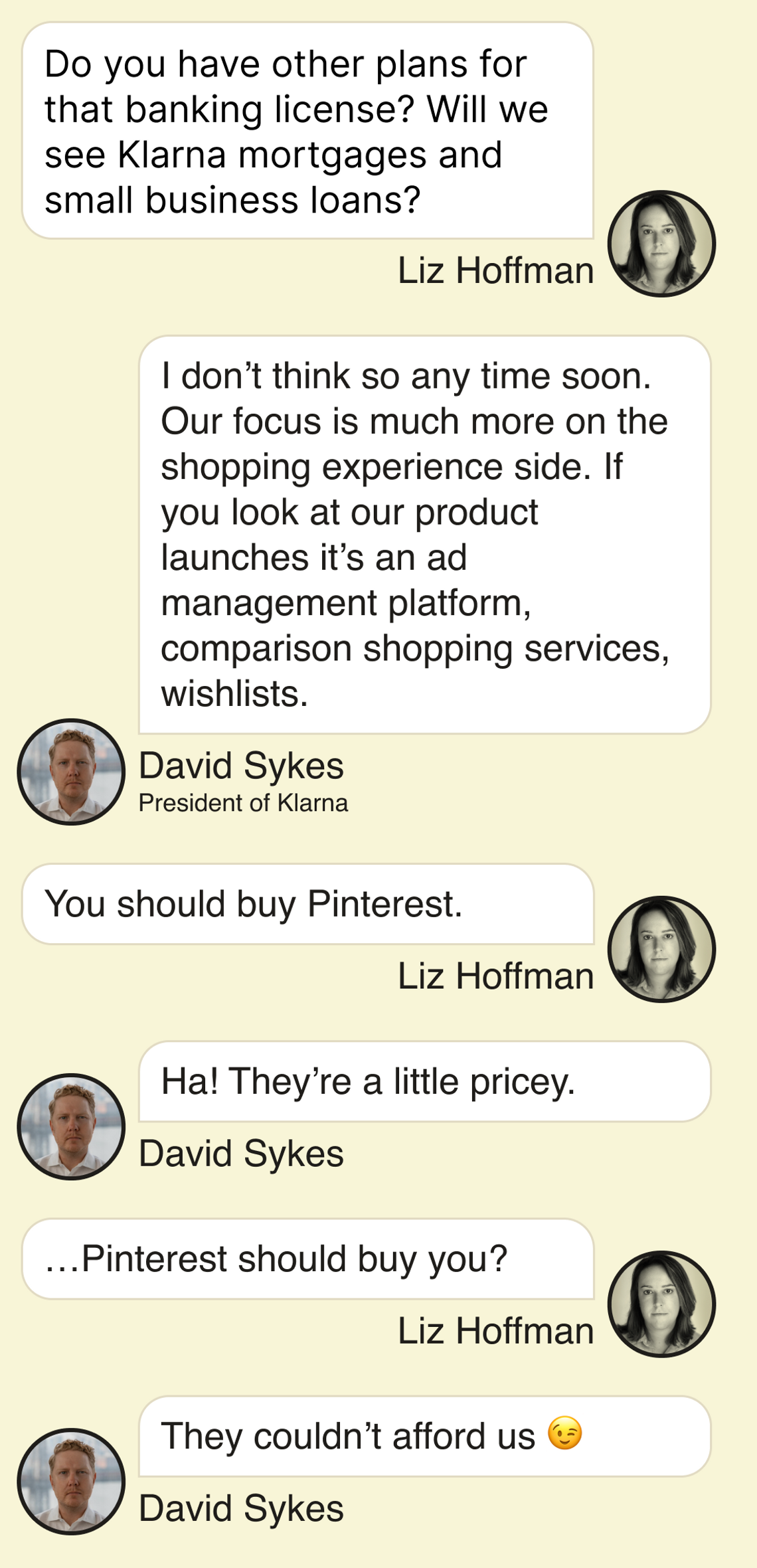

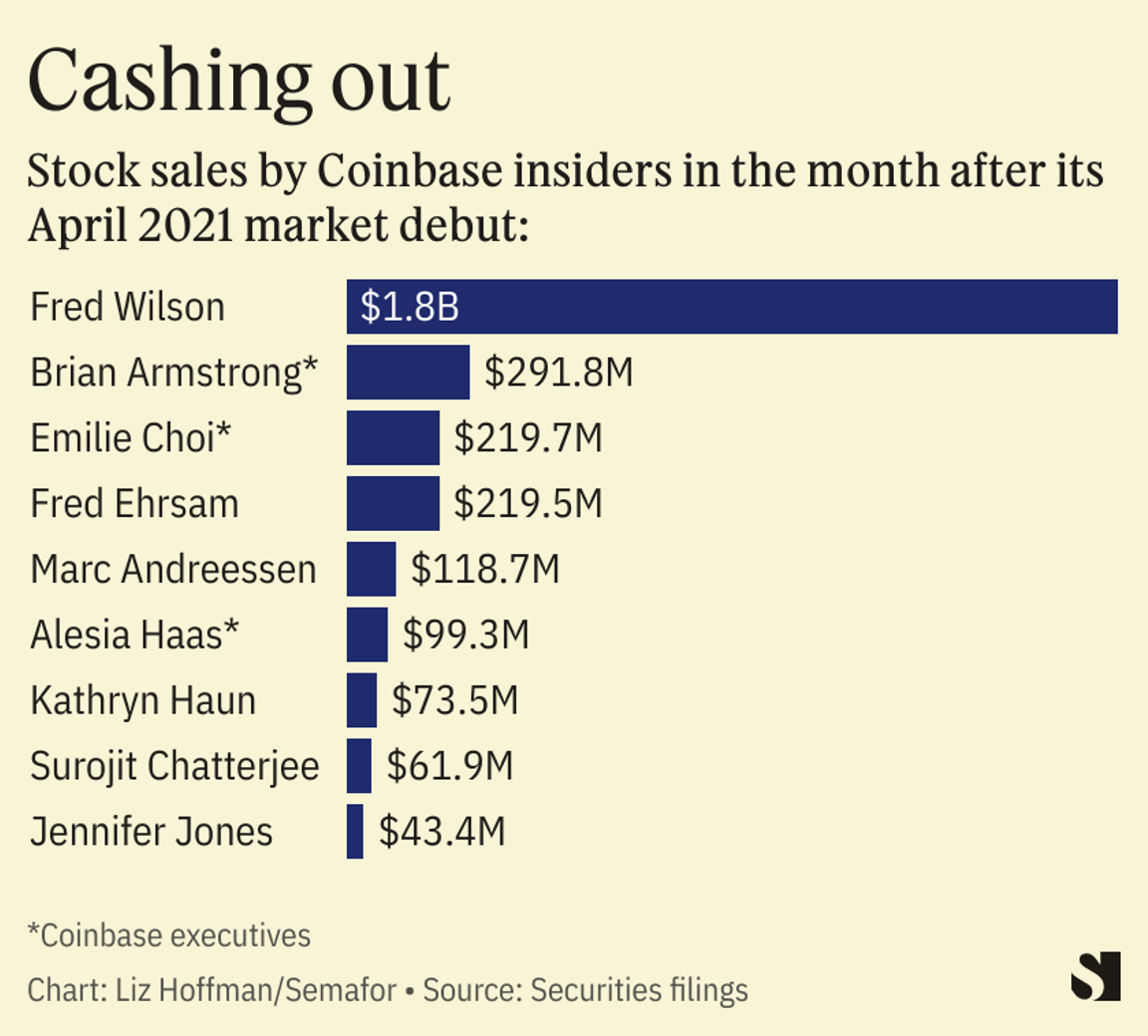

THE NEWS A new civil lawsuit accuses Coinbase directors and executives — a star-studded list of elite Silicon Valley investors including Marc Andreessen and Fred Wilson, along with the company’s CEO and its co-founder — of dumping shares soon after the crypto exchange went public, knowing it was likely to miss its financial targets. The nine named defendants, who include Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong and CFO Alesia Haas, sold $2.9 billion worth of stock in the week after the company’s market debut on April 14, 2021 and before it reported its quarterly earnings a month later, according to the shareholder lawsuit and confirmed by a review of the company’s securities filings. The lawsuit, filed in Delaware court and unsealed on Monday, claims they avoided more than $1 billion in losses by selling when they did. Over the next few weeks, the company reported earnings that fell short of expectations and raised new money in a deal that diluted existing investors. Between Coinbase’s listing on April 14 and April 22, Wilson sold $1.8 billion worth of stock, CEO Brian Armstrong sold $292 million, and Andreessen sold $119 million, the lawsuit and securities filings show. Coinbase declined to comment.  Semafor/Joey Pfeifer Semafor/Joey PfeiferKNOW MORE Coinbase’s market debut was a landmark event for the crypto industry, a sign that mature companies with solid management and sophisticated investors were replacing the Wild West of speculators and flim-flam artists. It was briefly valued at $100 billion on its first day of trading. A month later, it announced its first quarterly earnings as a public company, falling short of analysts’ expectations. The company’s fees on each trade — the main way exchanges make money — had shrunk from 1.4% to about 1.2%. The complaint cites internal board minutes and presentations, some of which are redacted, that show Coinbase’s executives and board members knew those fees were under pressure while they were selling their own stock. Shares fell 2.5%, and lost another 13% over the next few days as Coinbase announced a $1.25 billion in a convertible bond offering. (These bonds convert into stock, so they eventually make existing shares less valuable.) The day before the earnings announcement, shares closed at $265.10. By May 19, when it completed the bond offering, they closed at $224.80. LIZ’S VIEW Coinbase clearly needed money when it went public. Internal board minutes cited in the lawsuit show directors and executives were aware of that months earlier, and it quickly went out to raise cash. So why didn’t it do a traditional IPO, which would have brought in hundreds of millions of dollars? One reason could be that IPOs generally prevent insiders from selling their stock for a few months. These lockups are meant to instill confidence in investors that management is bullish on the company. Instead, Coinbase did a direct listing, in which no new shares are floated but existing ones are simply listed on an exchange. There’s no rule against having lockups in a direct listing — Palantir included one when it went public in 2020 — but most don’t. (There’s no rule requiring lockups in traditional IPOs either, but underwriters demand them and investors expect them.) That left Coinbase’s executives and venture investors free to sell, and sell they did. Nearly all of the trades by the defendants, who also include venture investor and former federal prosecutor Katie Haun, and Coinbase co-founder Fred Ehrsam, were conducted above the valuation that a consultant had placed on the company just before it went public, according to the lawsuit.  ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Coinbase pre-released some of its earnings figures on April 6, a week before it listed, projecting $1.8 billion of revenue and $1.1 billion, and it hit both numbers. Given that, it might be hard to argue that investors were in the dark during the period covered by the lawsuit. And the fact that this case is being brought by a plaintiffs’ firm, not securities regulators, may also suggest there’s less here than meets the eye. Bernstein Litowitz is a serious firm with a string of big wins behind it, but the Securities and Exchange Commission presumably saw the trades when they were disclosed, and chose not to pursue a case. NOTABLE - The transcript of Coinbase’s 2021 first-quarter earnings includes some back-and-forth between Haas and an analyst about the exchange’s slipping fees. Coinbase charges less for larger trades, and the growing size of each transaction was crimping margins.

|