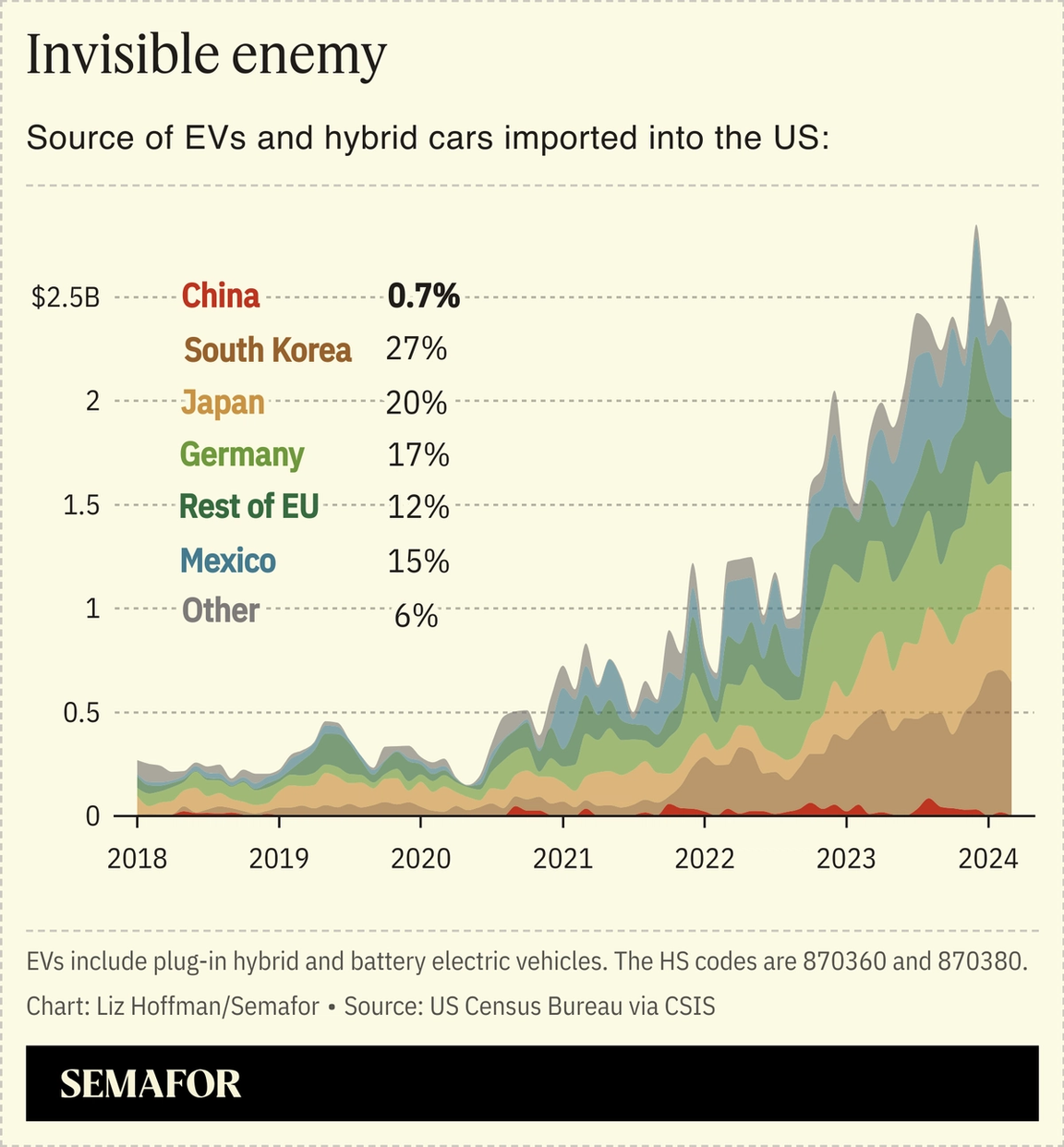

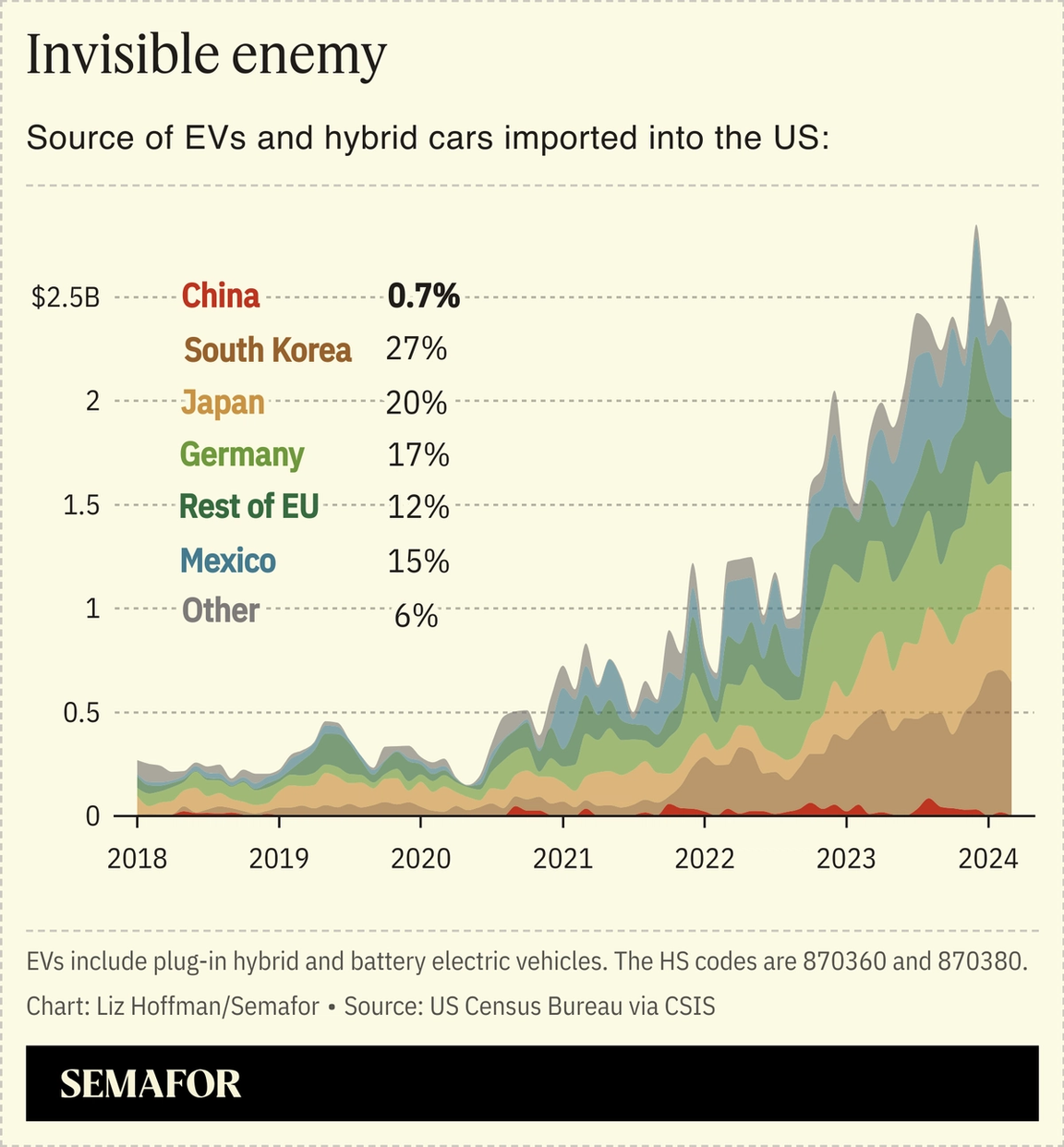

Two American companies have pending deals to be sold to foreign buyers hailing from US allies. Only one has run into the national-security buzzsaw — and it isn’t the provider of encrypted satellite communications systems. No political outcry or Pentagon rumbling followed the merger, announced two weeks ago, of Luxembourg-based SES and Intelsat, a Virginia-headquartered company whose satellites carry transmissions for the Air Force and the Army. Meanwhile, the sale of US Steel to Japan’s Nippon Steel has become a political lightning rod, with candidate photo-ops in front of unionized factories and a rare comment from the president hinting he’ll block the deal if it gets to his desk. Welcome to election-year M&A. Corporate dealmaking is always a political affair, but the 2024 election has raised the rewards for candidates who can seize on hot-button economic issues that could help them at the ballot box and make the road toward a sealed deal harder. Some of the year’s biggest mergers are being tripped up by politicians preening for voters and riding a broader wave of economic protectionism that has accelerated since the pandemic. This morning, President Joe Biden announced a wave of new tariffs on electric cars, semiconductors, solar cells, critical minerals, medical devices, construction cranes, and other goods from China. Nippon Steel has basically hung its hopes on after the November election. An executive this week predicted a “calmer discussion once the political leverage” of the United Steelworkers union, whose endorsement in the key voter state of Pennsylvania can make or break a race, “is gone.” But both Biden and Donald Trump have vowed to block the deal, and key constituencies who don’t often agree with each other — J.D. Vance and Sherrod Brown, steelworkers and environmentalists — all oppose the deal for their own reasons. It’s not just the US; half of the world’s population will vote in a national election this year, and all politics are local. BHP’s proposed takeover of Anglo American faces major government pushback in South Africa, whose president is in a reelection race so tight that he’s paused power cuts. That deal is also in the political crosshairs in Botswana and likely Brazil, where settlement talks over a deadly 2015 dam collapse at a mine have now turned to executive bonus bashing, a dependable campaign issue anywhere. Spain’s government opposes BBVA’s hostile bid for Sabadell, which would unite the country’s second- and fourth-biggest banks. “We have the last word,” Economy Minister Carlos Cuerpo said in an interview with Spanish television. And French President Emmanuel Macron this week hung a for-sale sign around his country’s banks, saying that Europe needs to get over its parochialism to compete with the US and China. LIZ’S VIEW Biden said it was “vital” that US Steel remain American-owned. Vital to whom? US Steel is no longer an American industrial titan. After decades of underinvestment, the company is the third-largest steel producer in the US and the 27th-largest in the world. It employs fewer people than News Corp or Swatch. The Defense Department supports a handful of companies that produce defense-grade armor with subsidies to ensure they can remain independent and healthy. US Steel isn’t one of them. “The 1980s called and want their industrial policy back,” said Ivan Schlager, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis who helps companies through national security reviews. The company remaining US-owned may be vital to the political fortunes of Biden and Pennsylvania’s senatorial hopefuls, who are donning hardhats and waving steel-mill union cards. But it is “mostly worthless to national security,” William Greenwalt, a former deputy undersecretary of defense for industrial policy, wrote in March. The deal will test a White House whose agenda has appeared more political than substantive in other ways. Tariffs rolled out on Chinese steel and electric vehicles — the former announced while Biden was on a campaign swing through Pittsburgh — are taking aim at an invisible enemy: China accounts for less than 1% of EV imports and about 2% of steel imports.  The funniest outcome here — and proof that election-year politics are trumping core governing principles — would be if US Steel is sold to Cleveland-Cliffs, a deal that on any other day would likely be blocked on antitrust grounds. Meanwhile, the SES-Intelsat deal will winnow a satellite-communications industry that’s been consolidating for years. The “shrinking gene pool,” as one industry trade put it, will leave the US military more reliant on Elon Musk’s Starlink and Amazon’s Kuiper system — not an ideal outcome. Even the curious approval of Exxon’s $60 billion takeover of Pioneer earlier this month had campaign-trail undertones. It swapped out one politically useful theme (corporate consolidation is bad) for another (the evils of Big Oil.) The new one got an immediate boost when The Washington Post reported that Trump promised oil executives that he’d roll back environmental regulations if they donated $1 billion to his campaign. Falling short in their efforts to convince Americans that the economy is, in fact, doing great, I expect the White House to pivot to a message of corporate collusion and greed. It softened the ground with its handling of the Exxon deal, and Biden’s top economic adviser this week urged raising taxes on companies and top earners. |