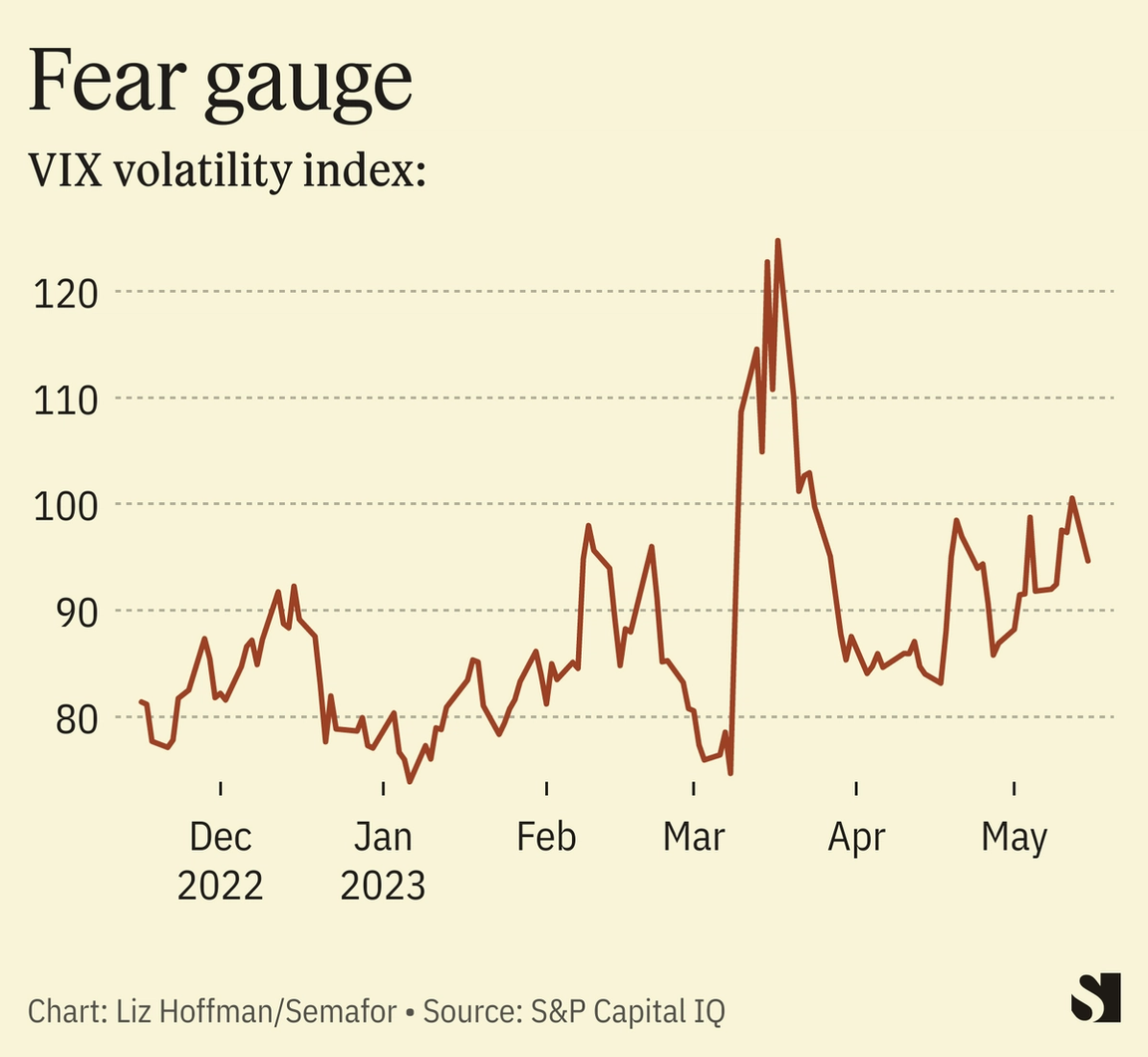

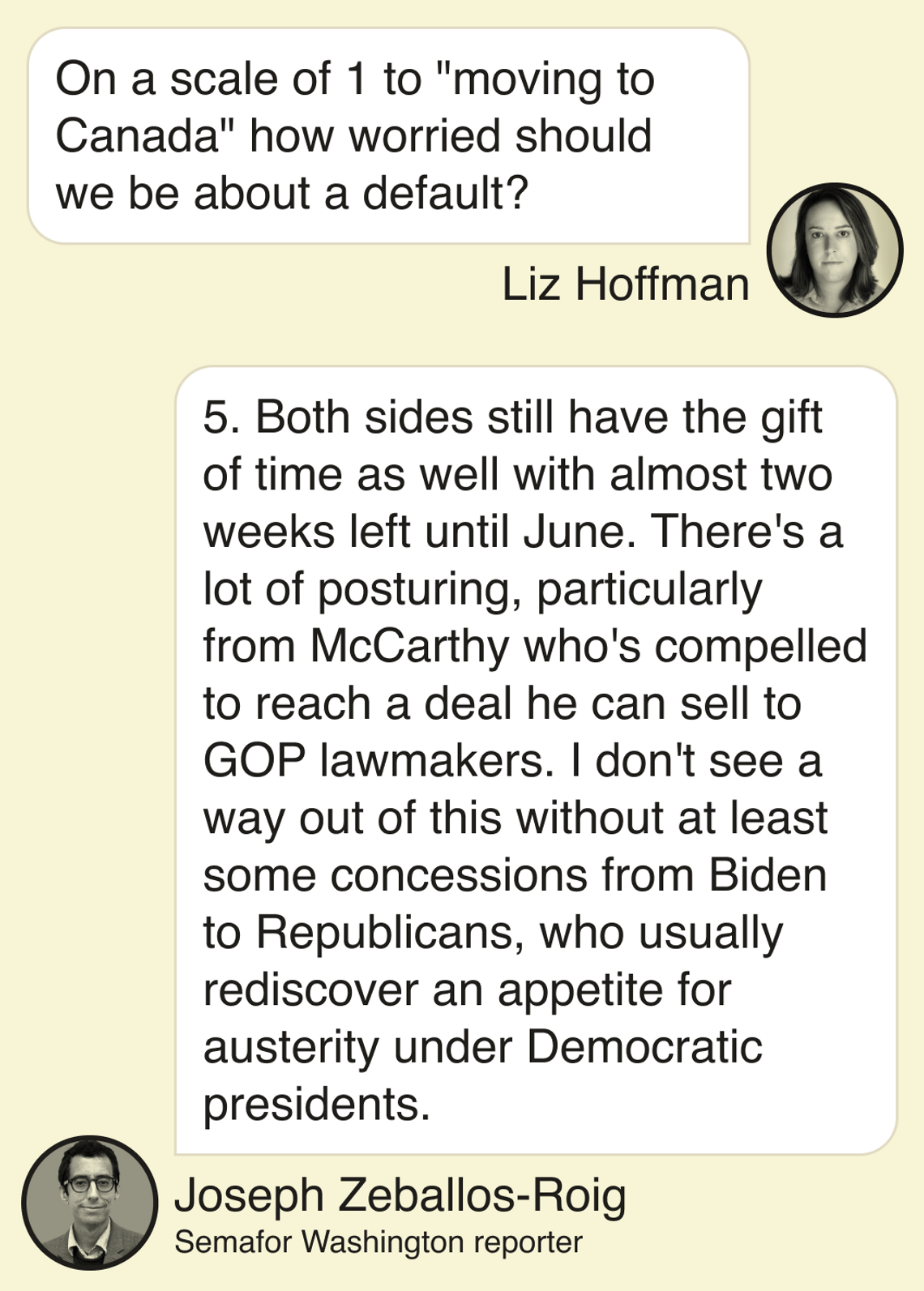

THE NEWS The U.S. Treasury’s borrowing costs have already increased “substantially,” Secretary Janet Yellen said Monday as she warned again that the government may not be able to pay its bills starting June 1, if Congress does not raise the debt ceiling. President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy are set to meet today to try to hash out a deal, with the two sides still divided over caps on federal spending and other issues.  Reuters/Saul Loeb/Pool Reuters/Saul Loeb/PoolTHE VIEW FROM THE BOND MARKET To understand how some investors are feeling about the prospect of a U.S. default on its national debt, take a look at a bond called 912796ZG7. On March 2, the Treasury Department raised $348 million to fund the military, Medicaid, and the rest of the nation’s business, with a promise to pay it back in three months. For the first two months of its existence, 912796ZG7 bopped along smoothly enough. In recent days its price has tanked, and anyone brave enough to buy it yesterday will get a 5.5% return, reflecting worries about a default. Its sister bond, 912797FG7, which comes due two days earlier, on May 30, was yielding just 3.2%. THE VIEW FROM THE STOCK MARKET Meanwhile, the S&P 500, the Dow, and Nasdaq were all up yesterday, despite McCarthy sounding pessimistic about a deal. And Wall Street’s measure of panic is lower today than it was during the regional banking crisis.  Wall Street’s Washington watchers believe a debt resolution is coming — and their clients are relatively sanguine. At a lobbyist roundtable Monday, one person in attendance said the mood was “extremely optimistic” given the conversations happening between White House and congressional staffers. Investors have also been consoled by contingency plans like invoking the 14th amendment, which may give the president the power to order that U.S. debts be paid anyway. But it would be challenged immediately in the courts. While even Yellen questioned the use of the 14th amendment as a viable solution, several Wall Street lobbyists said clients “have been calmed” by the option, which has never been used before. BRADLEY’S VIEW Bond investors have been a better predictor of U.S. policy — both fiscal and monetary — than their more positive-thinking peers in the equity markets. Stock investors this year have remained convinced interest rate cuts are just over the horizon though Fed Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly said that is not on the table this year. A recent report from Morgan Stanley put it bluntly: “Stock investors are too bullish” as persistent inflation means the Fed will be in no rush to cut borrowing costs. In the debt ceiling fight, there’s no more obvious sign of their optimism than their faith in the 14th amendment — a legal maneuver that will outrage Republicans. Bond market volatility, meanwhile, has been at levels matching the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the housing crisis in 2008, as fixed-income investors take Powell at his word that there’ll be no rate cuts this year. The last time the debt ceiling debate was this precarious — 2011 — bond investors in long-term treasuries ended the year up 16%, while equity investors needed close to 12 months to recover their losses. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Legendary bond investor Bill Gross isn’t too worried about a default and thinks everyone should load up on short-term treasury bills. “Not that it is a 100% chance, but I think it gets resolved,” Gross told Bloomberg last week. THE VIEW FROM CANBERRA Australia instituted a debt ceiling in 2008 to signal economic discipline and scrapped it six years later after repeated political gridlocks. “Australia flirted with this stupidity, then escaped it,” economist Richard Holden wrote. Only the U.S. and Denmark have set debt limits (Kenya is moving its to a percentage of economic output), and Denmark has never come close to hitting it, according to the Atlantic Council. NOTABLE - The Congressional Budget Office laid out the U.S. government’s financing needs through September to give a sense of what the funding hole could be if the debt ceiling isn’t resolved.

|