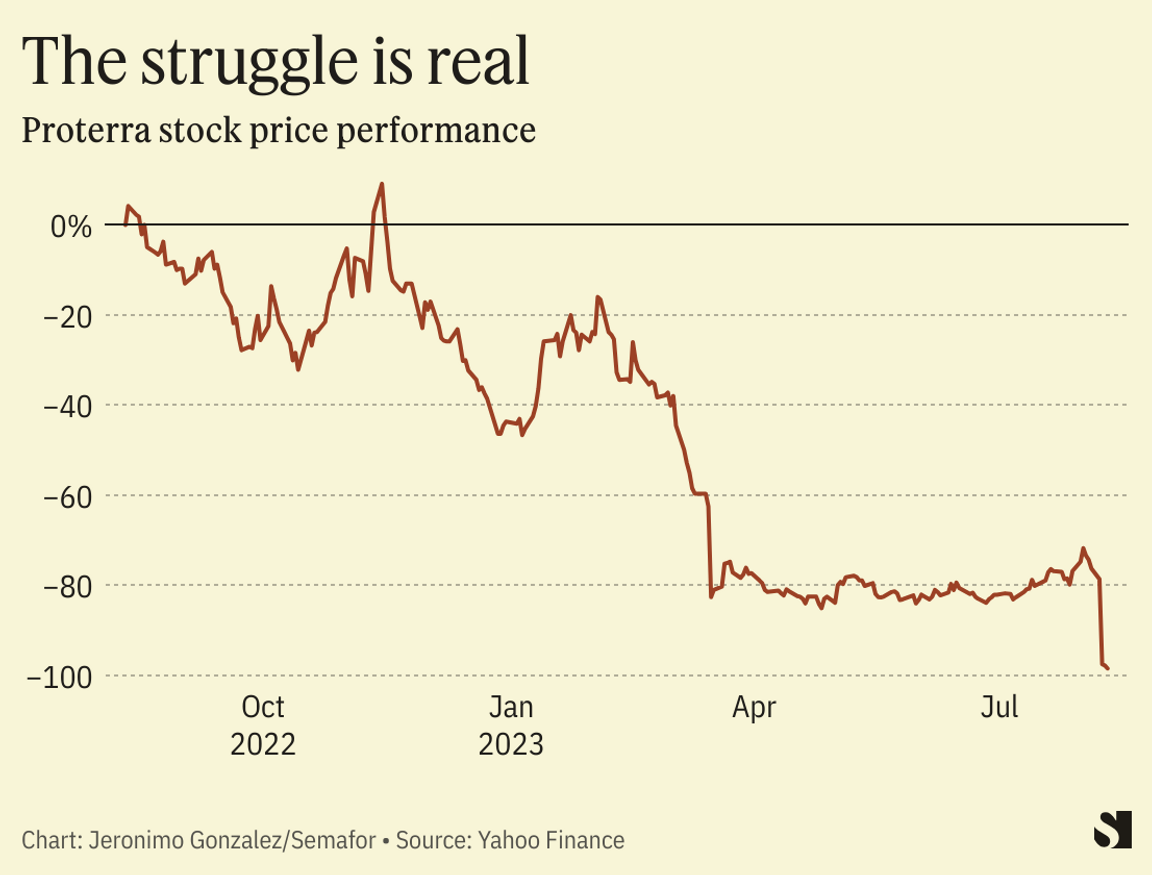

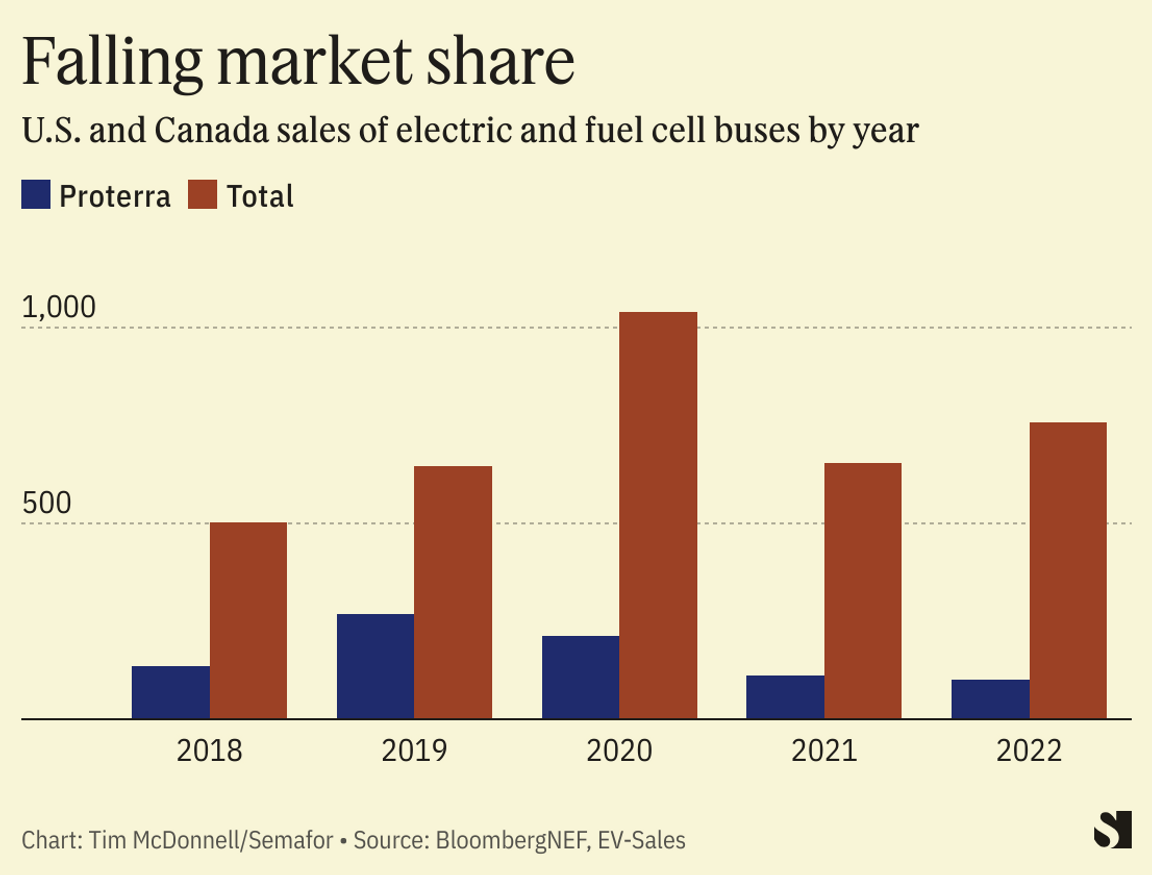

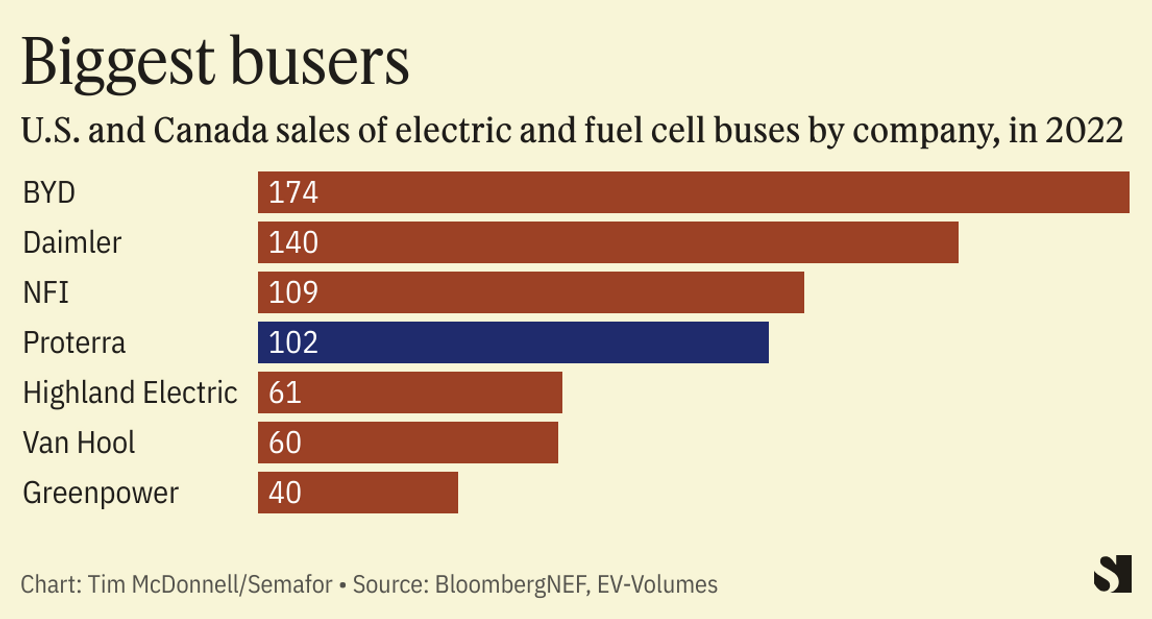

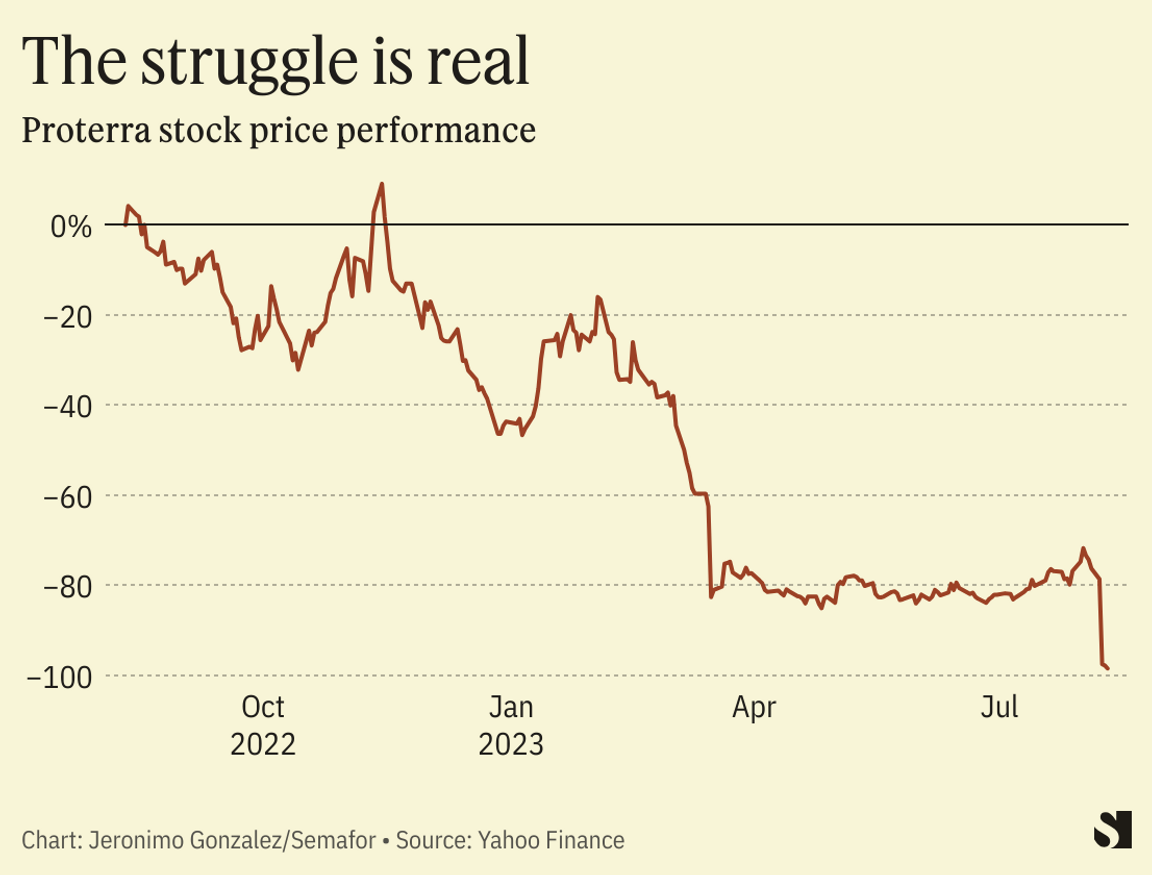

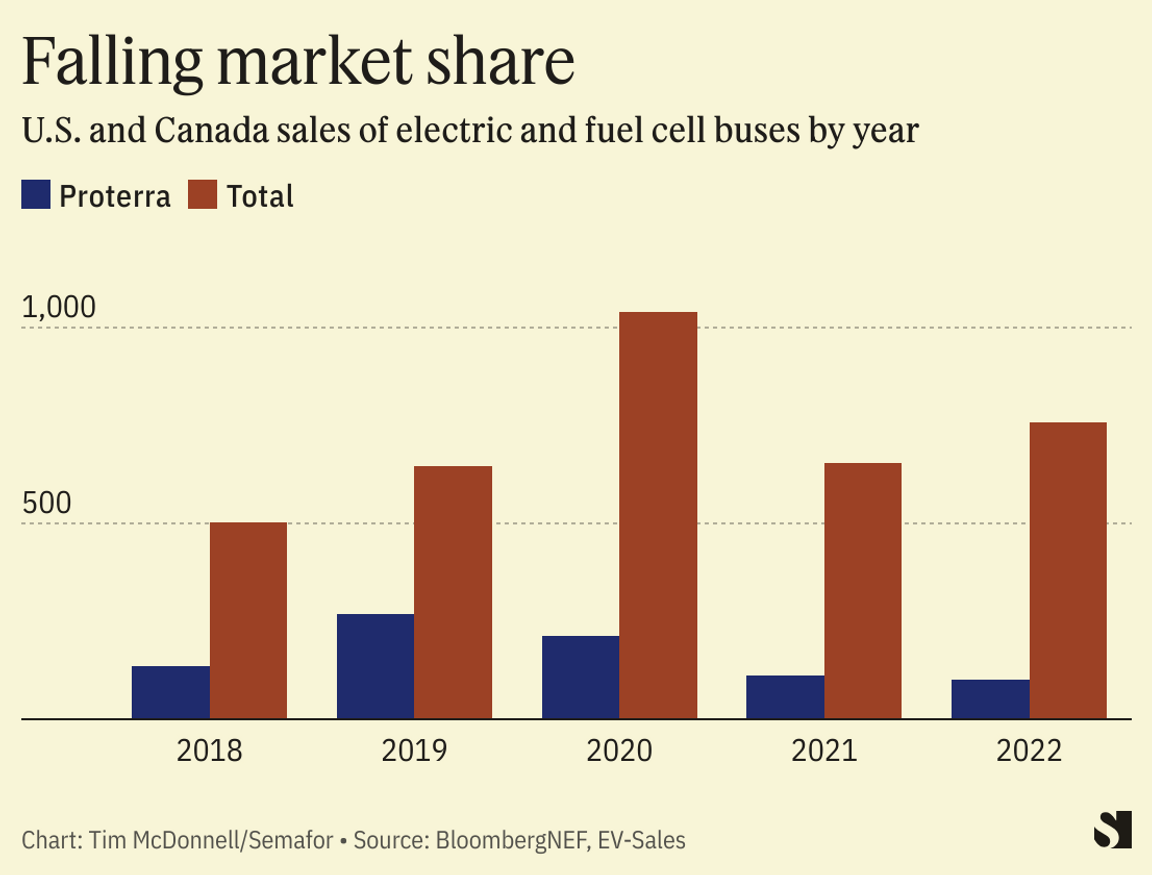

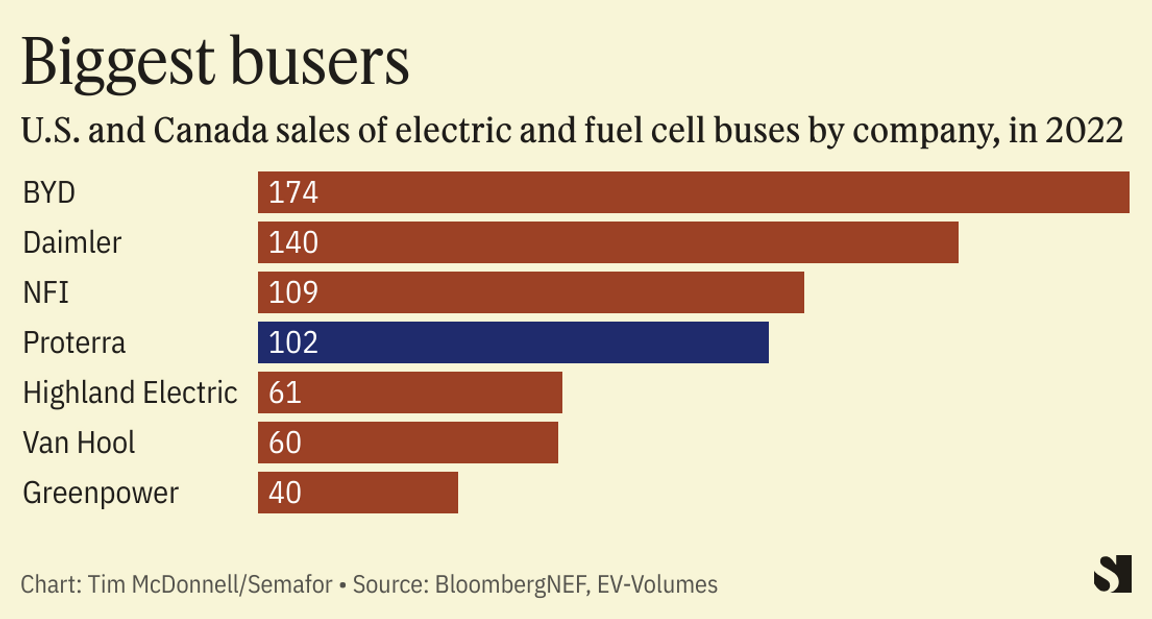

Courtesy Proterra Courtesy ProterraBy Tim McDonnell THE NEWS The largest maker of electric buses in the U.S. filed for bankruptcy this week, a move blamed on new product lines failing to overcome the high costs of e-bus manufacturing. But Proterra’s demise points to another issue: Even with unprecedented levels of government support and customer interest, some sectors cannot compete against top manufacturers in China. The company will slow down battery production but otherwise continue operations as normal for now while it uses the bankruptcy proceedings to either sell off or recapitalize the different sections of its business. TIM’S VIEW Proterra’s struggles reveal how difficult it is to run a profitable electric vehicle business in the U.S., even in a post-Inflation Reduction Act world.  Buses make a good candidate for electrification because they run on predictable schedules, in fleets. The high fuel consumption of traditional buses makes the lifetime ownership cost of an e-bus competitive or, depending on state and local subsidies, even cheaper than an internal combustion engine bus, according to BloombergNEF. But they have drawbacks as a business. Unlike passenger vehicles, buses are typically customized for each customer, limiting automation and factory efficiency. They get ordered in batches (when a city gets a new budget, for example), leading to inconsistent production schedules and orders with suppliers. They take a long time to build — 12 to 18 months from when a contract is signed to when a bus is delivered and paid for, in Proterra’s case — which makes them vulnerable to having their margins eaten away by inflation.  Proterra’s nickel-based battery chemistry was also more expensive than the lithium batteries used by most of its competitors, said Nikolaos Soulopoulos, head of commercial transport research at BloombergNEF. Its earnings report indicates the company spent $6.5 million more on materials for its products in the first quarter than the revenue those products generated. And ultimately, the domestic market is small: 750 e-buses were sold in the U.S. and Canada in 2022. The company reported a loss of $250 million in the first quarter of this year, five times more than in the same quarter last year, and laid off 300 staff in January. “It’s not something where you can change the fundamentals from one day to the next,” Soulopoulos said.  High production costs are universal for EV makers, from the tiniest startup to Ford and GM. BYD — Proterra’s main rival in the U.S. electric bus market — has addressed this problem through unparalleled economies of scale and by vertically integrating its supply chain. Tesla has cultivated a profitable side hustle in dominating the charging network. Major automakers still lean on their traditional internal combustion business for profit. In Proterra’s case, new business lines it launched over the last few years in batteries, charging stations, and electric drivetrains could have had a similar effect on cash flow (in addition to $10 million in forgiven pandemic stimulus loans the company accepted in 2020). Instead, according to the company’s bankruptcy filing, they held it back. (A Proterra spokesperson declined to comment, and referred all questions to the filing.) The company wrote that its bus business “requires a large amount of working capital” but that potential investors were more interested in the new sideline businesses and “not inclined to invest” in the company if it meant being exposed to losses from the bus division. To read the Room for Disagreement and View from the Passenger Side, click here. |