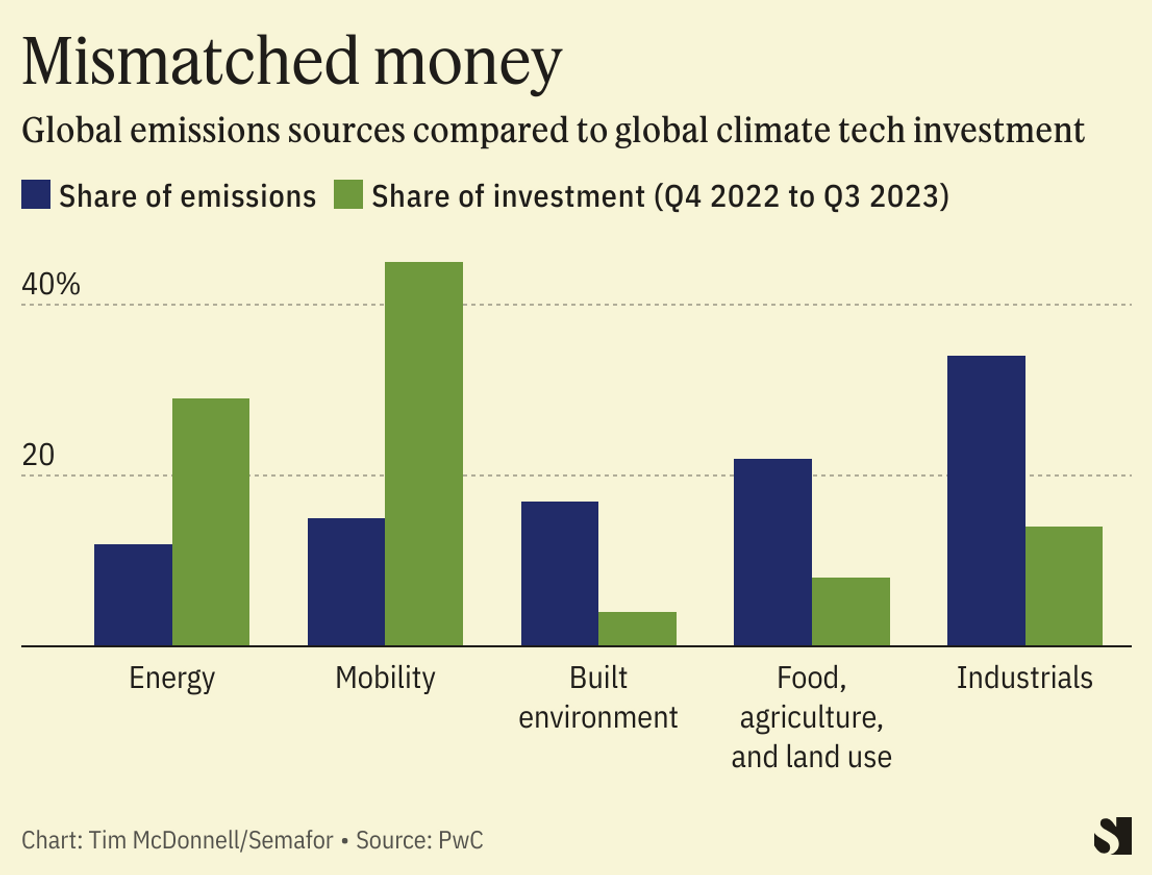

REUTERS/Tyrone Siu REUTERS/Tyrone SiuTHE NEWS A sector responsible for around a quarter of energy-related carbon emissions could drastically reduce its footprint with solutions that are well-known, inexpensive, and easily deployable. So why doesn’t it? That is the question vexing experts and officials about the so-called built environment — the buildings and homes we live and work in. A growing number of countries and cities around the world are finally taking action, both when it comes to ensuring that new buildings are energy-efficient and erected in as sustainable a way as possible, and in making existing sites less carbon-intensive. The latter is particularly important in rich nations, as much of the building stock has already been constructed. As a result, governments, notably in Europe, have promoted wide-ranging efforts to expand “retrofitting” to improve energy efficiency in existing homes and offices using well-known and tested systems: Italy offers a 110% tax credit on “green” home renovations; the Netherlands last year launched an energy-saving education campaign and a push to better insulate a third of its homes with grants and low-cost financing; Danish authorities aim to discontinue gas boilers by around 2030 and also switch large numbers of homes to district heating, where an entire neighborhood relies on a single heating source, allowing for greater efficiency. Businesses, too, see an opportunity: Schneider Electric last month promoted software it said could cut a building’s carbon emissions by up to 42%. “Existing buildings are the biggest challenge and the biggest opportunity” for emissions reductions in the built environment, Peter Templeton, CEO of the U.S. Green Building Council, told my colleague, Tim McDonnell. The USGBC, which oversees environmental ratings for buildings, issued new guidelines last month that require owners to make deeper cuts to their energy consumption in order to maintain a high rating. “It’s something actionable that doesn’t take a decade-long permitting cycle.” PRASHANT’S VIEW Even though so many of the solutions to reducing carbon emissions in this sector are well known and understood, efforts to cut emissions in the “built environment” suffer from a number of real-world obstacles. For one, the costs of energy inefficiency aren’t always born by the building owner: When it comes to residential and commercial property, renters typically pay electricity and gas bills, not landlords, who have little incentive to spend what can often be major sums (and leave their properties unoccupied) for improvements that do not measurably increase the rent they can ultimately charge. And for new construction, many building and infrastructure developers are wary of trying new or higher-cost materials, particularly when concrete, for example, remains cheap. “A lot of this is just risk aversion,” Chris Bataille, an adjunct research fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, said on a recent CGEP podcast. Finally, the issue — particularly retrofitting — is boring. Discussion of the energy transition inevitably focuses on cutting-edge technologies, sophisticated financial reforms, and controversial legislation and regulation. Politicians are rarely excited to trumpet policies that promote improved insulation or which tout turning the thermostat down a degree to save energy, meaning the effort is often drowned out by more headline-grabbing problems and solutions. |