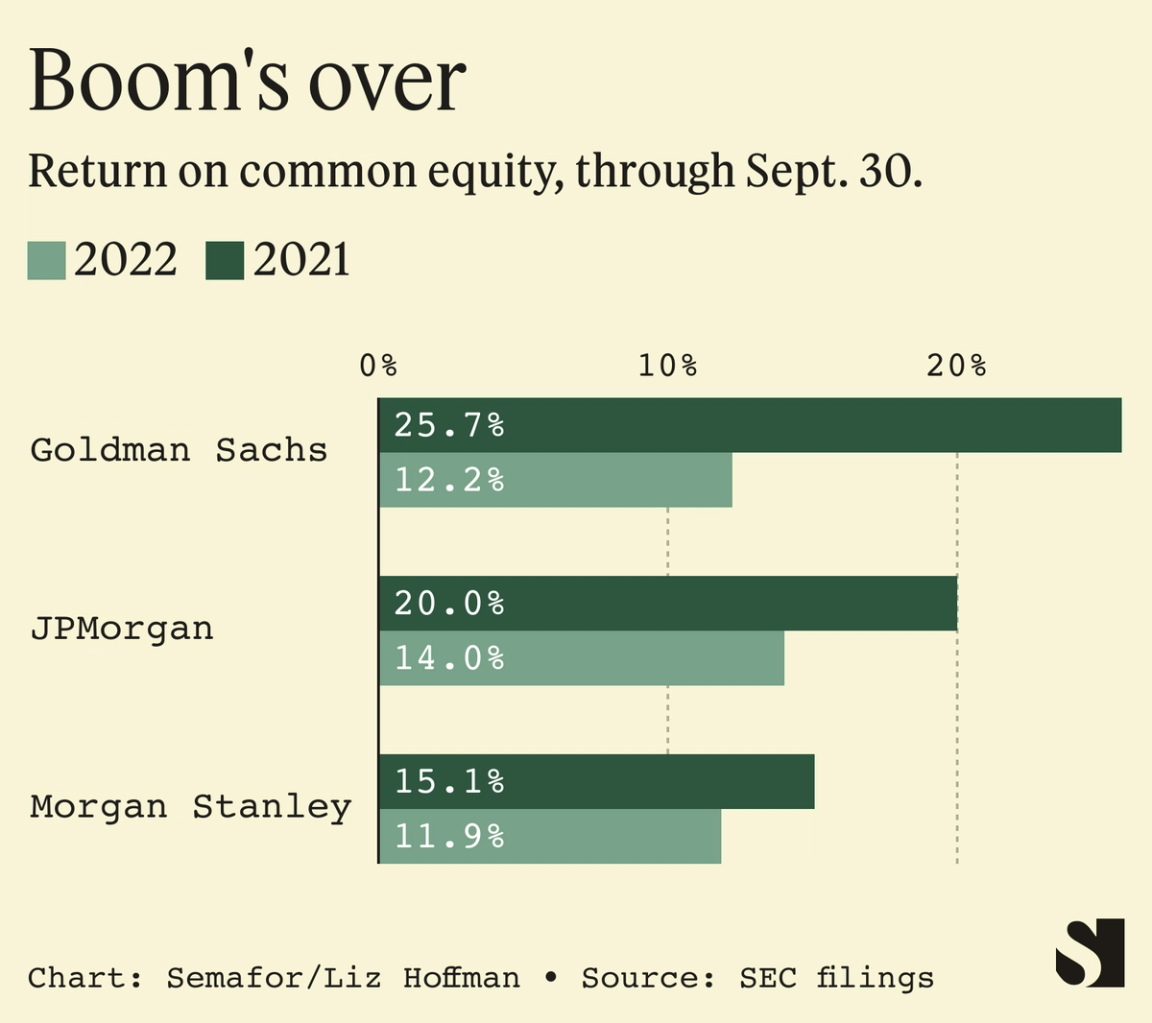

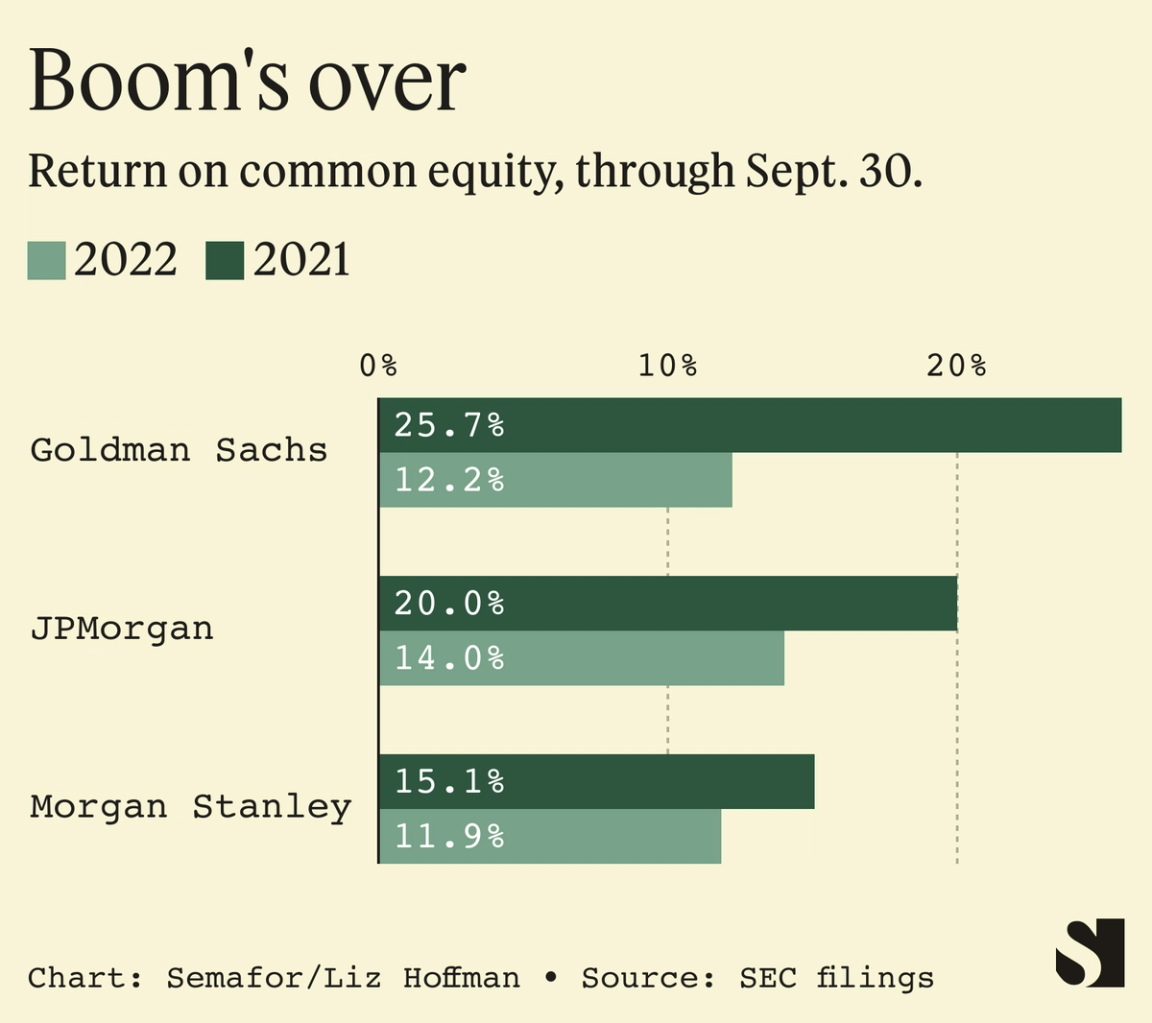

THE SCOOP Goldman Sachs’ bonus pool for senior employees is expected to shrink by as much as half, people familiar with the matter said, as CEO David Solomon tries to boost flagging shareholder returns in a tough year across Wall Street. A smaller bonus pool for its 400-odd partners isn’t surprising, at least directionally speaking. Last year was a huge year for high finance, and compensation reflected that, while 2022 has been a rough one. But Goldman’s revenue, which tends to be a proxy for pay, is only down 20% over the first nine months of the year, so the expected cuts look deeper this year. It will be finalized by the end of the year. In February, the firm set a new goal of raising its return on equity — a measure of stockholder gains — to 14%. But then the markets boom of 2021 went poof, and profits are down across Wall Street. As of Sept. 30, Goldman’s figure was at 12%. There’s only so much money to go around and the choice, as it is for all CEOs in lean times, is between courting investors and rewarding employees.  LIZ’S VIEW Solomon has been more attuned to shareholders’ concerns than his predecessors, holding investor presentations and shedding some of the firm’s signature secrecy Partly that’s because he has to be — Goldman isn’t the undisputed king of Wall Street anymore — and partly because a higher stock price just makes everybody happy. (I covered the firm for five years, and you can take the resting pulse of Goldman headquarters at 200 West Street by just checking the stock price.) Now with smaller profits, he has to pull the levers carefully, striking a balance between keeping the partnership happy and keeping his promise to shareholders. It’s an unenviable position. The internal howling from cutting partner pay is inevitable – but also extremely predictable. After last year’s windfall, Goldman gave its partners a special stock awared, and was careful, as I wrote at the time, to “gift-wrap it as a one-time event and keep their expectations in check going forward.” It came with a public warning, too, from the company’s chief financial officer, who told analysts that “to the extent the environment in 2022 shifts, that compensation model is highly variable.” But Wall Street memories are short, and this will produce some internal hand-wringing. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Goldman has to answer to shareholders, just like most other public companies. The New York Times in 2018 created what it called the Marx Ratio, a measure of how companies shared their profits with employees versus shareholders. Big banks rated surprisingly low, as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine noted at the time. |