The News

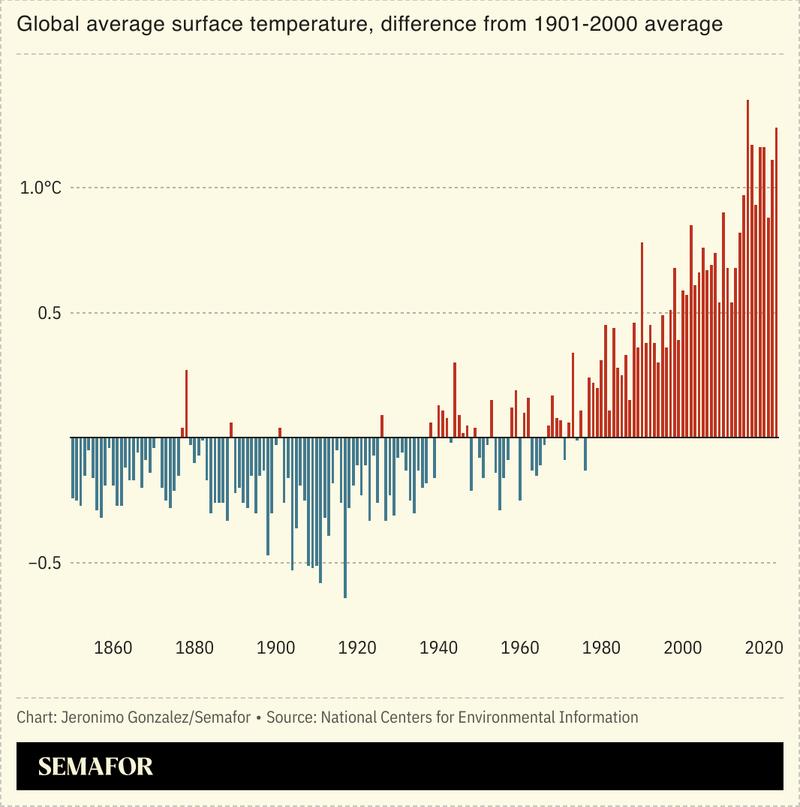

Global average surface air temperatures were 1.5°C warmer than the pre-industrial levels during 2024, new data showed, the first time the threshold was broken for an entire calendar year.

The international 1.5°C Paris Agreement target has not yet been missed, as this refers to a decades-long average — but last year’s record brings the world “teetering on the edge” of doing so, an expert at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts warned.

SIGNALS

The threshold is politically important, but also arbitrary

Though legally binding, the 1.5°C degree limit is somewhat arbitrary, a climate scientist told the BBC: “It’s not like 1.49C is fine, and 1.51C is the apocalypse — every tenth of a degree matters and climate impacts get progressively worse the more warming we have.” And although the number has become politically and symbolically significant, it’s similarly arbitrary as a metric for measuring when climate change becomes dangerous, since millions of people have already had their lives devastated by climate-related disasters. What matters is not the precise value of the temperature rise but “the simple fact that it is continuing to rise,” the scientist said.

Costs of climate change are already upon us

2024 was a year of climate superlatives: “The broken records in the ocean have become a broken record,” the lead scientist of a recent study on ocean warming remarked. The last 12 months saw “all corners of the globe” endure extreme weather with devastating consequences for people’s lives and livelihoods, from deadly cyclones in Bangladesh to wildfires in Canada, Climate Council wrote. A report by the International Chamber of Commerce found that such events have cost the global economy more than $2 trillion over the past decade, while the World Economic Forum has estimated the global cost of climate change will be between $1.7 trillion and $3.5 trillion a year by the middle of the century.

Effects of LA fires to be felt ‘for years, if not decades’

Climate change is a driving force of the ongoing wildfires in Los Angeles, the BBC reported. The economic effects of the emergency will be felt “for years, if not decades,” long after the fires have subsided, Heatmap noted, from the long-term health risks of smoke inhalation to the high level of insured losses leading insurers to shed policies. Southern California’s already crippling housing crisis is likely to worsen, The New York Times wrote: The displacement, plus damage to housing stock, means “a positive shock in demand, and a negative shock in supply,” an economist said, driving rental prices up around LA and possibly leading to an increase in homelessness.