The News

The biggest U.S. oil and gas companies are getting bigger — and that may actually be good news for the climate.

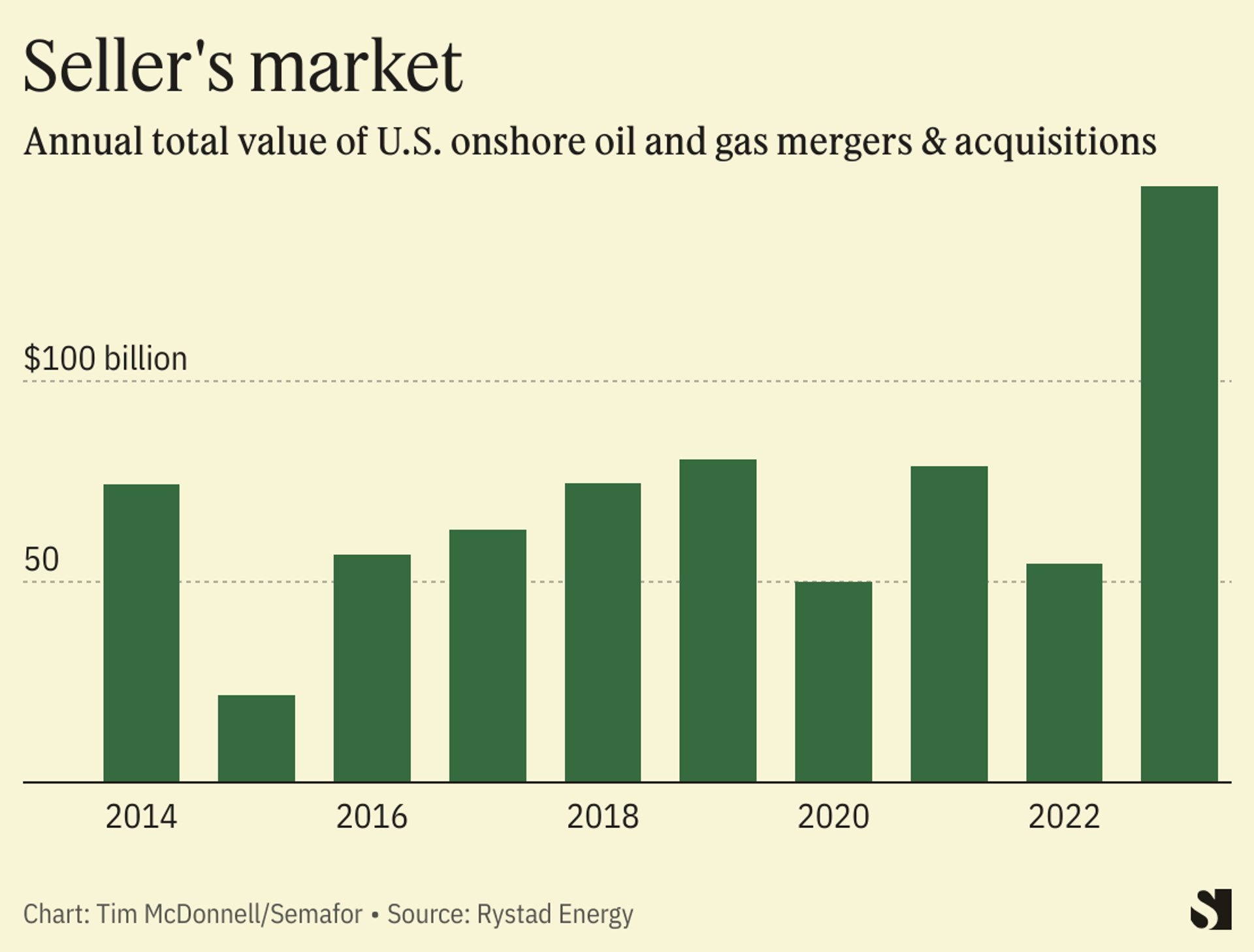

Chesapeake Energy, a midsized Oklahoma-based natural gas producer, merged last week with Texas-based Southwestern Energy in a $7.4 billion all-stock transaction, creating what is now the country’s largest gas company. The deal was designed to give the new company a competitive edge in the Gulf Coast gas fields that are feeding a major boom in liquefied natural gas exports. It comes amid a record wave of consolidation in the sector over the last six months, driven by a race among investors to snap up the most profitable drilling sites as they face the impending decline of fossil-fuel demand.

“The name of the game is securing the inventory so the company can still exist as a business within the next couple of decades,” said Matt Bernstein, senior analyst at Rystad Energy.

Tim’s view

The biggest oil and gas producers are flush with cash after a couple of highly profitable years, but are under pressure from their shareholders not to plow that money back into new production. As companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron plan for their existing wells to run low and oil demand to decline, and with few untapped resources left, the most cost-effective way to maintain market share has become to acquire a smaller rival and run its wells more efficiently. Gas companies are under similar pressure to find efficiencies, especially because gas prices have fallen since the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Recent big deals include Exxon’s acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources and Chevron’s purchase of Hess, both in October, as well as APA’s acquisition of Callon Petroleum on Jan. 4, along with numerous other small deals, mostly in the Permian Basin.

That trend should help the sector drive down its carbon footprint. Smaller producers are more reactive to short-term price trends; when prices rise, they race to open new drilling rigs, usually leading to overproduction and price crashes. A larger post-merger company will in theory have a steadier hand, and a production budget that is smaller than the sum of the two pre-merger companies, both of which should result in lower overall output, said Andrew Logan, senior director of oil and gas at the sustainable finance advocacy group Ceres.

Larger production companies are also more willing and able to reduce their own operational (scope 1 and 2) emissions. They have bigger budgets for monitoring and emissions-control measures, and if they are publicly listed, are accustomed to reporting emissions data that private companies can more easily conceal (the reverse is also true: When majors offload production assets to private companies, the assets’ emissions tend to increase.) Prior to its merger with Chesapeake, Southwestern had a target to reduce, but not eliminate, its operational emissions by 2035. Post-merger, the combined company will adopt Chesapeake’s more ambitious target to reach net zero by that date. Larger companies may also be better positioned to invest in developing energy transition technologies like carbon capture or hydrogen, or to acquire climate tech startups, like Occidental’s $1.1 billion purchase of Carbon Engineering in August.

In general, the consolidation wave is a sign that Big Oil investors know the end is near, Logan said: “An industry with decades of growth ahead of it doesn’t need to consolidate. An industry that is approaching sunset does.”

Room for Disagreement

The downside of consolidation, from an emissions perspective, is that the newly created companies are laser-focused on longevity. The most attractive acquisition targets are those with the lowest operating costs, and thus a breakeven point that can withstand future low oil prices. That gives companies an incentive to keep them running far into the future.

“You want to have your investments in areas that are most likely to be the ‘last drop’,” Bernstein said.

Larger companies also have more political muscle. Federal regulators are already looking into the Exxon and Chevron deals to see if they violate antitrust laws. Jeff Colgan, a political scientist at Brown University, recently argued in The New York Times that Big Oil consolidation means “more money for lobbyists, industry interest groups and media advertising, all of which undermines efforts to pass legislation strong enough to meet the world’s climate goals.”

Know More

Big Oil’s big contraction likely isn’t finished yet. There are still several large privately-owned companies in the Permian that could make attractive targets; in December, Endeavor Energy, the largest remaining one, said it was considering putting itself on the market. And Diamondback Energy, a smaller publicly-traded producer that hasn’t yet entered the M&A fray, has said it wants to be a buyer, not to be bought.

There’s a gold rush mentality to the consolidation wave, Bernstein said, that is driving prices to previously unseen levels; when Occidental bought CrownRock in December, it paid nearly six times what CrownRock was expected to earn in 2024, whereas typical multiples for acquisitions prior to the current wave were more like 2-3 times earnings, Bernstein said. Endeavor’s price tag could be up to $30 billion, unaffordable for all but the largest majors. Instead, Bernstein expects the focus to shift more to “mergers of equals” like the Chesapeake and Southwestern deal.

Whatever action there is in the year ahead is likely to stay concentrated in oil, not gas. In the Chesapeake deal, the companies were willing to place a long-term bet that LNG export prices will rise for the next few decades. But at the moment, gas prices are low and projected to stay that way, which has sapped most companies’ acquisition budgets.

The View From Nigeria

Meanwhile, some majors continue to dump their high-cost, high-environmental-impact assets. On Tuesday, Shell agreed to sell its onshore production business in Nigeria to a group of local companies for $1.3 billion, finally leaving a market where it had faced years of accusations of human rights abuses and oil spills. The sale passes the responsibility of maintaining Shell’s aging infrastructure in the Niger Delta, and of cleaning up its 50-year legacy of pollution, to the local companies.