The Scene

Metallica is helping the nascent hydrogen fuel industry thrash its way into existence.

When the iconic metal band goes on tour across Europe this summer, some of its guitars and drums will be hauled in trucks powered by hydrogen fuel cells. The band is keen to cut the carbon footprint of its tours, said Gerrit Marx, CEO of the Italy-based truck manufacturer Iveco Group, which is designing custom low-carbon trucks for the tour: “Everywhere they have concerts, we can engage together on sustainability.”

The Iveco collaboration makes Metallica the latest advocate for hydrogen, a controversial fuel that could eventually be critical to the clean energy transition but the global supply of which is currently made almost exclusively from unabated fossil fuels. Marx spoke to me on stage during Baker Hughes’ annual meeting in Florence, Italy, where some of the world’s biggest investors in hydrogen said the key to realizing the fuel’s green aspirations is to turn a blind eye, for now, to how it gets made. Instead, they’re chasing any possible end user — from steel plants to metal bands — to scale the industry up on the expectation that falling costs for renewable energy and carbon capture technology will eventually make hydrogen a genuine solution to climate change.

“We’re getting into the era now that hydrogen is becoming a reality,” Lorenzo Simonelli, Baker Hughes’ CEO, said in an interview. “We have to invest early on in what we see as the future horizons even though the infrastructure associated with [low-carbon] hydrogen may not be there today.”

Tim’s view

Hydrogen has a chicken-and-egg problem: The tiny amount of hydrogen made from renewables is far more expensive than natural gas, making it uncompetitive as an alternative fuel for factories or transportation. But scaling up green hydrogen production and lowering prices won’t be possible without more buyers.

And if green hydrogen production doesn’t scale up quickly, some energy economists have warned that lifecycle emissions from “blue hydrogen” — where hydrogen is made from fossil fuels but carbon is captured at the end of the process — may be no better than just sticking with gas. Even with new tax-credit support in the U.S., high interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic have further undermined the economic case for green hydrogen, said Pierre-Etienne Franc, chairman of Hy24, a hydrogen-focused investment fund.

The key to changing the fate of green hydrogen, Franc said, is to find a handful of projects that can be economic on a large scale today, to prove out the investment case for more marginal future projects. Hy24 has invested in H2 Green Steel, the world’s largest steel plant run on green hydrogen, which is under construction in Sweden. That project has been able to draw nearly $7 billion in debt and equity because it has the right combination of cheap electricity and price-tolerant customers, he said: Sweden has abundant hydropower, and H2 Green Steel was able to sign advance sales deals for most of its production capacity with automakers for whom the cost premium of green steel is small enough be passed on to customers without attracting much notice in the overall price tag of a car.

Fertilizer derived from green hydrogen for industrial farms may be another promising early case, as well as long-distance trucks like the ones Metallica will use. But Marx cautioned that the green hydrogen space is already getting too crowded with prospective producers and hardware providers who are all clamoring for a piece of what will ultimately be a small pie, profit-wise, given how fierce the price competition between hydrogen and natural gas will be for the foreseeable future.

“Everybody thinks this is a huge gold rush,” Marx said. “It’s not, because the end customers are not going to pay for this gold rush. So we need to bring back a dose of realism when it comes to what margins can be made in this new industry.”

Know More

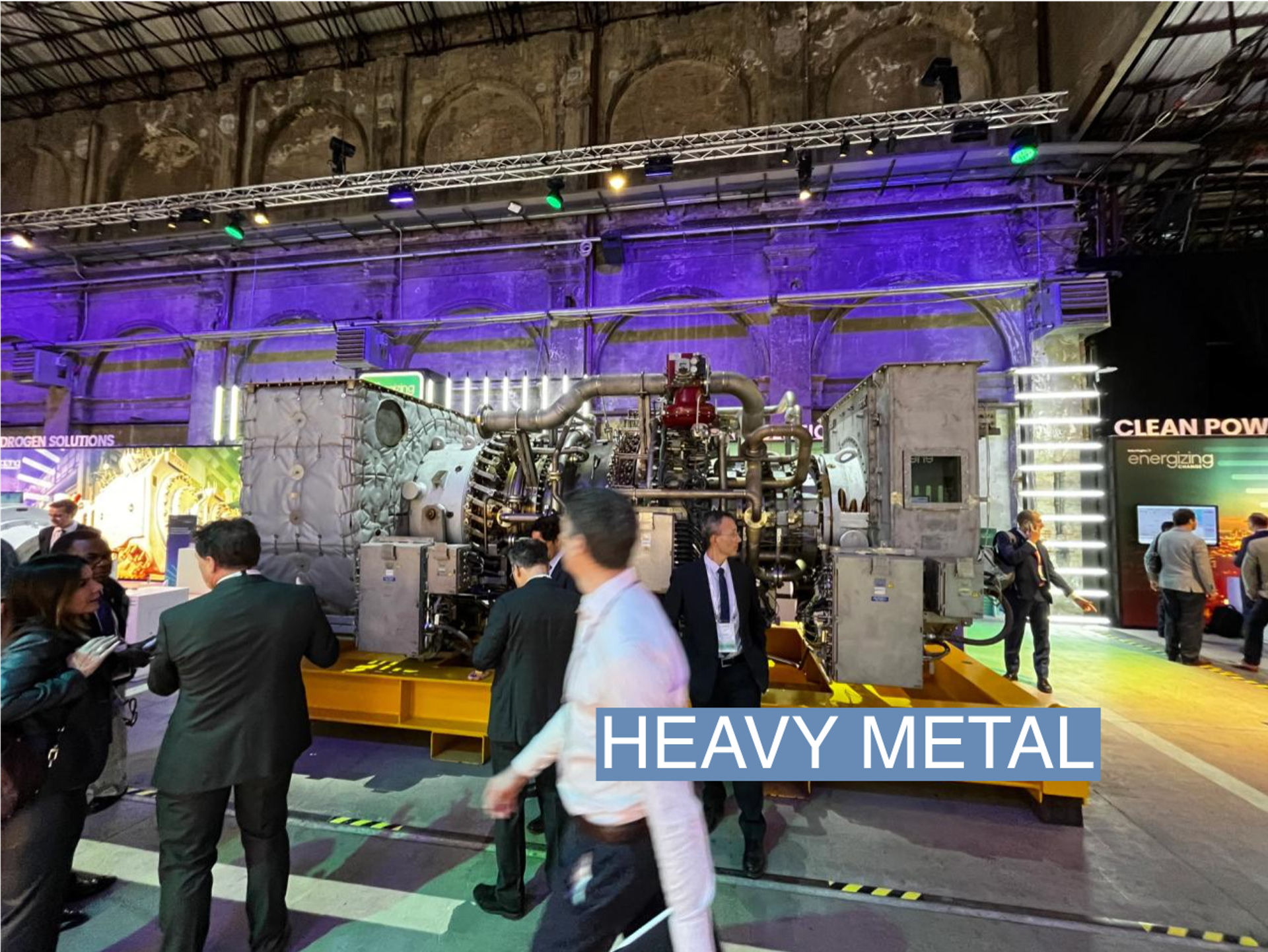

Baker Hughes’ approach to cracking the chicken-egg problem — and seeding a new business line that can survive the global pivot away from oil and gas, its bread and butter — is to develop hardware that can switch between running on natural gas and hydrogen. In Florence, the company’s prized showpiece was its first gas turbine capable of running seamlessly on any blend of hydrogen, up to 100%. The turbines, which can be used for electricity production or to push gasses through long transportation pipelines, lower the bar to entry for potential green hydrogen buyers: If the price of green hydrogen goes down, they’ll be ready, but in the meantime they can continue to use carbon-based hydrogen or natural gas. That flexibility helps industrial companies to justify spending money today on new gas-consuming infrastructure, including power plants, pipelines, and LNG terminals, that without hydrogen on the horizon would be at risk of becoming a stranded asset as regulatory pressure on emissions escalates.

The new turbine “may cost a little bit more, but the flexibility provides you with a 40-year runway,” Simonelli said.

Baker Hughes is also developing technology exclusively for green energy. It owns a chunk of the electrolyzer startup Nemesys and has provided engineering support and hardware for green hydrogen compressors for the Texas-based e-fuels company HIF Global and for NEOM, the world’s largest green hydrogen production facility, under development in Saudi Arabia. But the company ultimately is agnostic about which types of hydrogen get used in the future, Simonelli told me. Most likely, he said, the hydrogen supply will still come mostly from fossil fuels for years to come, with a growing share of that being produced as blue hydrogen.

The View From China

At the Baker Hughes conference, everyone in the hydrogen sector was looking nervously over their shoulder at China, which currently controls half the world’s production capacity for electrolyzers, the machinery that uses renewable electricity to split hydrogen atoms out of water. Even though it’s critical to bring down the cost of electrolyzers, it may be necessary to consider more trade barriers and targeted support for domestic electrolyzer manufacturing, or else much of the upside from early, higher-risk green hydrogen projects will ultimately flow to Chinese manufacturers, as happened with U.S. and European support for early solar panel and EV battery technology, said Alessandra Pasini, president of the hydrogen project development firm Zhero.

“We need to try to avoid the mistakes that were made in the solar industry, but the reality is if we don’t act soon, we risk being in that situation,” she said.

Room for Disagreement

Some green hydrogen investors are skeptical about the role oil companies like Baker Hughes can or should play in the sector’s development. Mark Hutchinson, CEO of Australia’s Fortescue Future Industries, said the sector has little genuine interest in anything that could cut into demand for its core products.

“It’s pretty clear that the oil and gas world wants to just keep doing oil and gas,” he said. “If the world’s waiting for this industry to be the solution [to green hydrogen], it ain’t gonna happen.”