The News

The world’s largest mining project will begin production by the end of the year following decades of delays, Guinea’s mining minister told Semafor — with 5% of eventual revenues earmarked to expand the country’s education system.

Initial shipments from the Simandou mountain range in southeast Guinea — home to the planet’s largest high-grade iron ore deposits — are due to begin by the first quarter of 2026, Minister of Mines and Geology Bouna Sylla said on the sidelines of the Mining Indaba conference in Cape Town.

The ambition to boost Guinean education with mining profits is the latest attempt by an African government to ensure its citizens benefit from natural resources, which are otherwise typically shipped elsewhere for refining: Sylla likened his government’s plans to those rolled out in previous generations by Southeast Asian nations, singling out Singapore in his comparison.

The British-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto and China’s Baowu Steel are among the companies that have partnered with the Guinean government on the $15 billion project.

In this article:

Alexis’s view

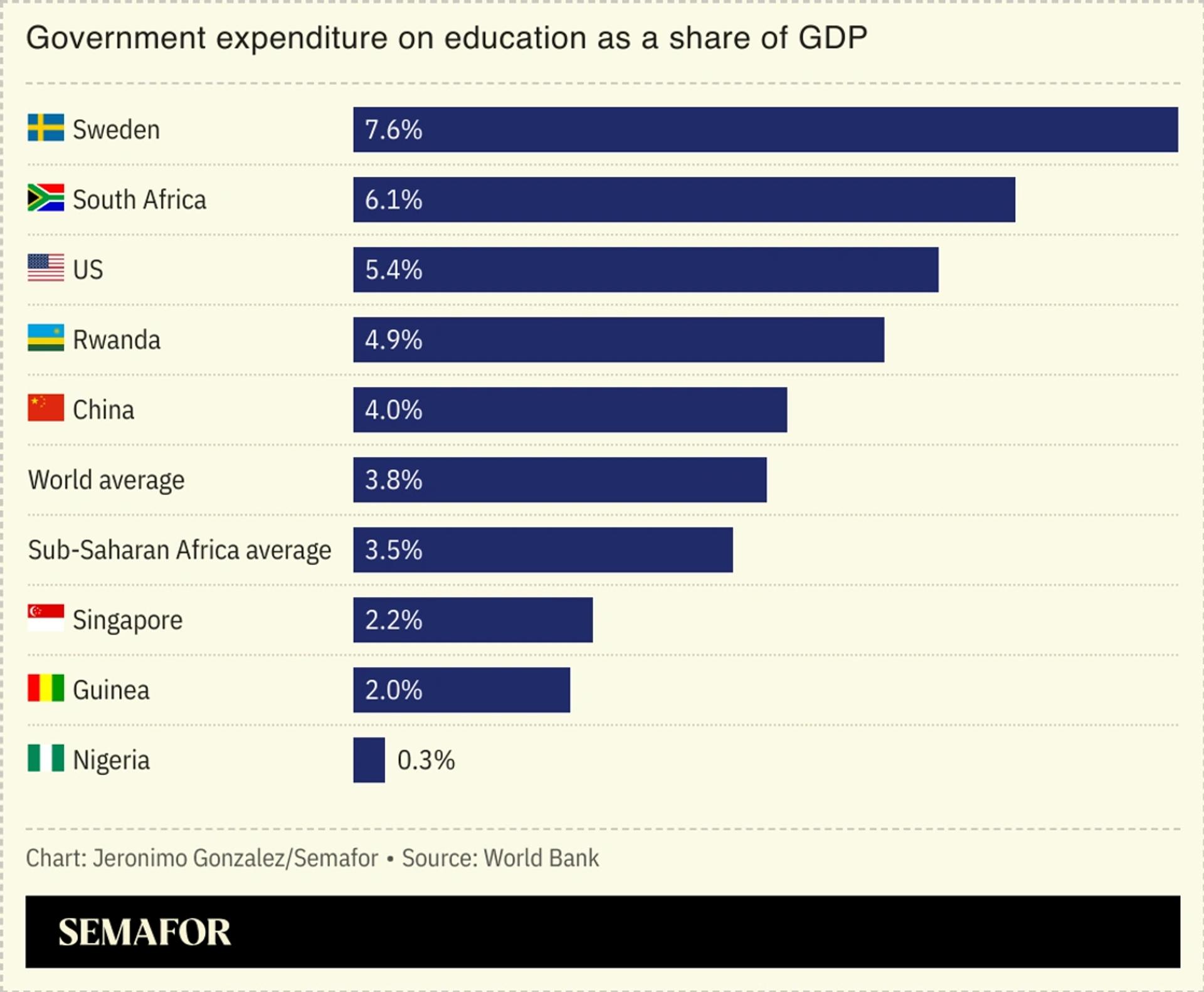

Guinea’s plan to earmark revenues from its natural resources marks an acknowledgment of the skills gap — particularly around science and technology — that is holding back economic development in many African countries. Guinea, for example, currently only spends 2% of its GDP on education, barely half the global average, and well below the 3.5% typical of sub-Saharan African nations.

That could be about to change as part of a broader trend. About 30% of global mineral reserves can be found in Africa, and politicians from across the continent say they want this wealth to improve their citizens’ lives, avoiding the experience of previous governments in the scramble for the region’s resources.

Countries are adopting different approaches: Ghana wants to use its iron ore deposits — which are of a lower grade than Guinea’s — to boost local building construction. Elsewhere in West Africa, the aim is simply to redress the balance with international companies in revenue-sharing agreements.

In Guinea’s case, Sylla said 5% of the tax revenues generated at each of the two mines at the Simandou site would be allocated to Guinea’s education system, over the next 25 years, starting from the launch of production — funding that would come on top of the usual education budgetary allowance. Under a separate program, the government plans to allocate 20% of state revenue earned from La Compagnie du TransGuinéen (CTG) — a joint venture that manages railway and port infrastructure built as part of the Simandou project — to fund high school students studying science and engineering abroad, also over 25 years.

Our “long-term sustainable investment is in human capital,” Sylla told me. “This is to invest in a new generation so that when the resources finish, people can come to Guinea to invest not because we have natural resources but human capital — technicians and engineers — like Singapore.”

Still, all of this will take time. The Simandou project has been beset by nearly 30 years of delays, and Guinea’s education program will take at least a generation to bear fruit. The government hopes its plans will show all of this has been worth the wait.

Know More

Simandou is typically referred to as the world’s largest mine project due to the value of the massive high-grade iron ore deposits, along with the size of investment, and the rail and port infrastructure create. Guinean government advisers told Semafor some $15 billion had been invested in the project, although the figure of $20 billion has been widely reported.

Sylla said 120 million tonnes of iron ore — used in steel production — will eventually be produced annually from Simandou, but it will take up to three years to ramp up to this capacity. He also said Guinea aims to transform iron ore to steel in a local plant that will produce 500,000 tonnes of steel per year.

In the bauxite sector, the minister said Guinea will produce alumina and then aluminium. Guinea signed an agreement last month with a Chinese company to produce 1.2 million tonnes per year of alumina that he said is expected to be ready by the end of 2027.

The View From THE US

Gracelin Baskaran, director of the critical minerals security program at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, said production at Simandou “will give Guinea a lot of value in the world of commercial diplomacy because we want more iron ore that’s not going to China.”

But she said the climate skepticism of the new Trump administration meant Simandou’s high- grade iron ore — which results in lower carbon emissions in the steelmaking process as a result of its higher quality — will enter a “bifurcated” market.

“You have the EU, where decarbonization is important,” and “America, where that is not important right now,” she said. “When you sell to Europe, you can sell at a price premium because you’re responsibly sourced. Nobody in America is going to pay that now.”

Notable

- Euronews examines why it took Rio Tinto 27 years to edge towards production at Simandou.

- South Africa’s mining minister said the country should withhold access to its minerals after the US president threatened to withdraw funding over a new land law.