The News

LAGOS, Nigeria — Deep divisions in Nigeria’s two main parties have burst open with just over two weeks to go until the presidential election, making it tougher for their candidates to get the broad nationwide support needed to win.

The ruling All Progressive Congress (APC) and the main opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) have been embroiled in arguments along geographic dividing lines ahead of the Feb. 25 vote. It threatens to scupper hopes of a first round win for their candidates since the victor must secure at least one-quarter of the vote in two-thirds of the country’s 36 states and the capital.

Nasir El-Rufai, a senior APC figure and the governor of northern Kaduna state, last week accused people in the president’s office — known as the villa — of deliberately undermining their own party’s candidate Bola Tinubu through disruptive policies, such as the issuing of redesigned naira bank notes in the run-up to the election which has led to a cash shortage.

“I believe that there are elements in the villa who want us to lose the elections because they didn’t get their way,” El-Rufai said in a live TV interview on Nigeria news station Channels. “They had their candidate but their candidate didn’t win the primaries.”

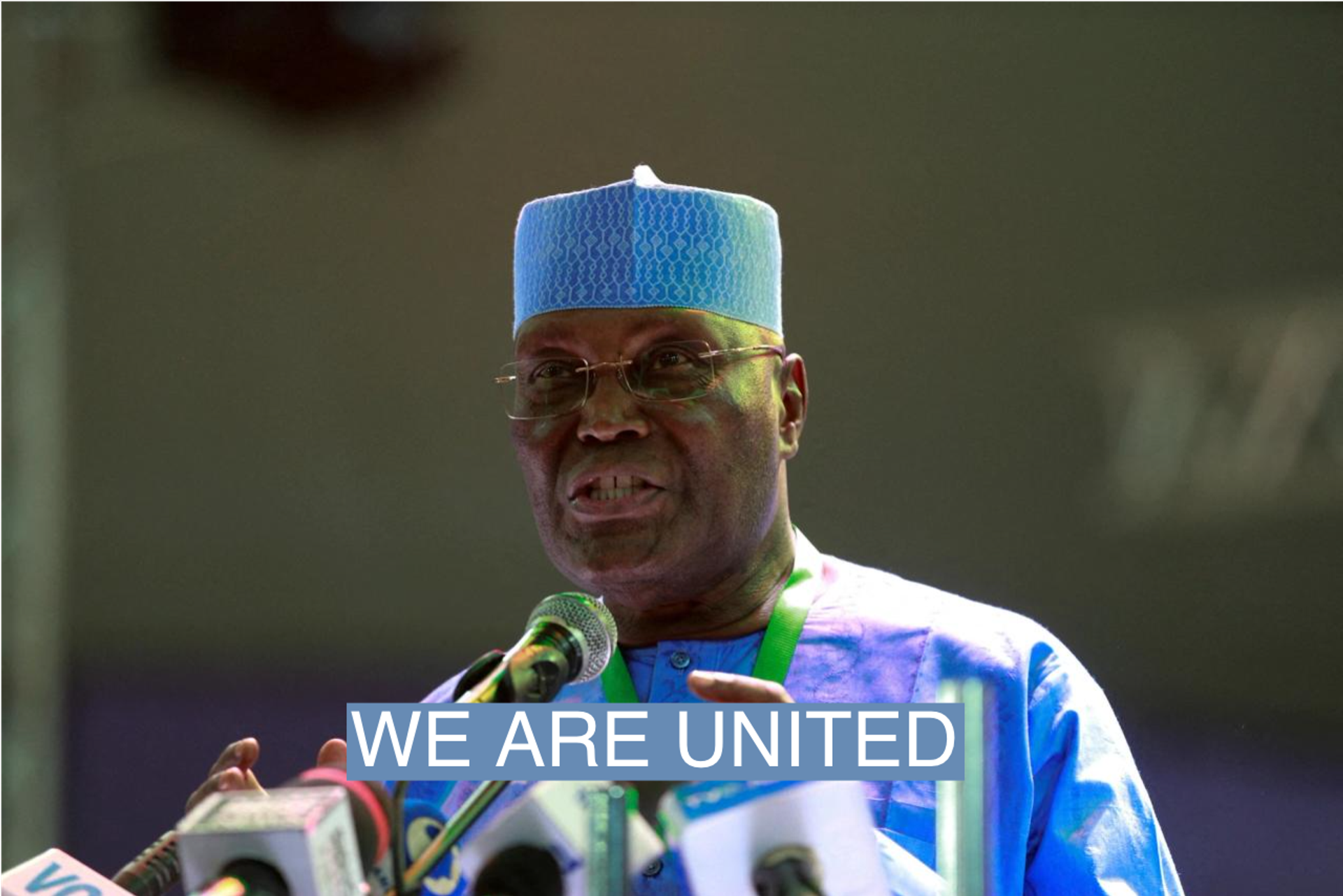

Meanwhile, five PDP governors in southern states, known as the G5, have refused to publicly back the party’s northern candidate. They have discussed switching their allegiance from Atiku Abubakar, commonly referred to as Atiku, to one of the other presidential candidates, according to people with knowledge of the talks.

In this article:

Alexis’s view

The fractures opening up within the main parties have blown Nigeria’s election wide open. The internal warfare is helping third candidate Peter Obi, of the much smaller Labour Party, to steadily gather momentum. Obi remains the frontrunner among decided voters in a number of opinion polls, with little over two weeks until the vote.

The APC’s divisions are pitting Tinubu, whose support is concentrated in the southwest, against the mainly northern inner circle of President Muhammadu Buhari. The party was formed in 2013 through the merger of Buhari’s Congress for Progressive Change, which had a stronghold in the mainly Muslim north where the Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups are dominant, and Tinubu’s Action Congress of Nigeria whose stronghold was in the predominantly Christian and Yoruba southwestern states.

If Tinubu loses the backing of his party’s northern power brokers — some of whom may feel they have a better chance of retaining influence under fellow northerner Atiku, of the rival PDP — he could be stripped of their crucial support in that part of the country, which has the most voters.

The daily problems confronting ordinary Nigerians, along with the suggestion that it may have been partly orchestrated to pursue intra party battles, will also turn some voters against the ruling party.

Even if Atiku benefited in northern states from an anti-Tinubu campaign by a cabal within the APC, his chances of amassing the geographical spread of votes needed to win in the first round would be diminished by the G5 backing his opponents in southern states.

Obi is benefiting from the internecine warfare that has gripped Nigeria’s established parties, but the former state governor from the southeast lacks broad support across northern states. And the Labour Party, which he fronts, lacks the infrastructure of offices, governors and paid street thugs needed to maximize voter turnout nationwide.

It means the splits threaten to push the vote to a runoff, which hasn’t happened since the end of military rule in 1999.

Room for Disagreement

Atiku’s spokesman, Phrank Shuaibu, sought to downplay the stories of discord in the PDP. “The G5 governors aren’t a threat, neither is there any major division in the party,” he told Semafor Africa.

An APC spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

Last month, after previously refusing to get drawn into campaigning, Buhari said he would join Tinubu at 10 rallies, which could be a boost for the APC candidate in Nigeria’s northern region. At a campaign event on Saturday, the president said: “I have known him for more than 20 years, and I will continue to campaign for Bola Ahmed Tinubu.”

The View From Lagos

The upcoming election was the last thing on many ordinary Lagosians’ minds on Wednesday as they struggled to get hold of their cash amid the chaos of the new naira note swap. Branches of two banks were shut without warning in the Surulere district of Lagos, leaving scores of frustrated bank customers standing outside in the tropical heat.

The closures, which have happened across the country, have followed the rationing of redesigned bank notes. On the streets, cars lined up in long lines leading to petrol stations rationing fuel amid a scarcity that started late last year and shows no sign of easing.

“I feel this whole suffering is needed,” said film editor Joshua Osamwonyi, arguing that people complained about the government during the EndSARS 2020 protests against police brutality but “people forgot and moved on” with their lives. “Now that this government has renewed the suffering, maybe they will think about changing who they vote for,” he said.

But against the backdrop of cash and fuel shortages, some told Semafor Africa the election was not a priority. Tunde Oluwaseun, a taxi driver said he did not register to vote. “If the leading candidates were proclaimed dead today, it’s not my business. I am not interested,” said the father of three, explaining that he was left disillusioned by past candidates who were disappointing in office, particularly Buhari after his 2015 campaign.

Oyeronke Ojudu, who sells eggs for a living, said the search for bank notes had left her exhausted. “I lined up for more than four hours two days ago but still didn’t get cash. My legs felt like they had been chopped off when I tried to stand up yesterday,” said the mother of five. “Do you expect a person who hasn’t eaten to stand in a line to vote?”