The News

The biggest publicly traded oil and gas companies are rethinking their approach to the energy transition after a year that made clear just how much money they can still make from their core fossil fuel products.

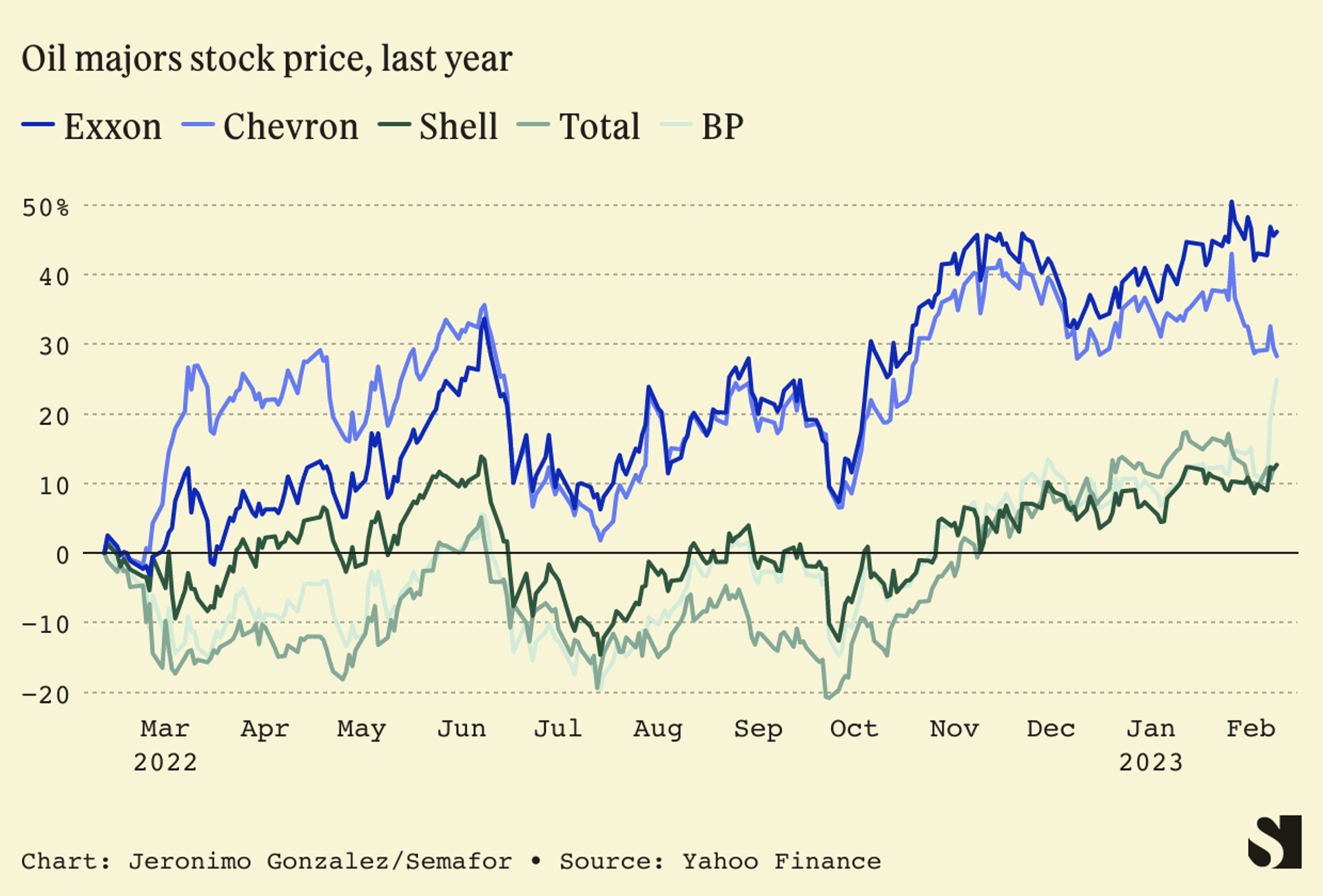

Over the last two weeks, the top five Western oil majors — ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Shell, and Total — posted $196 billion in profits, more than double the previous year. The boost came from high oil and gas prices as Russian energy was excised from the global market, and refined products saw record-breaking margins.

Normally, high profits would give them the room to make increased investments in new oil and gas projects or accelerate their transition to cleaner forms of energy, but not this time. The companies are instead plowing cash into share buybacks and higher dividends, to placate investors who are still smarting from record-breaking losses during the pandemic.

Tim’s view

Oil and gas companies do have strengths that could be brought to bear on the energy transition, including brilliant engineers and expertise in managing complex global supply chains and geopolitics. But they have two constituencies whose interests are often opposed, and to play a more credible and useful role in the transition, they will need to get better at pleasing both. It’s not yet clear if that’s possible.

The first is the general public and policymakers in their home countries, who for the most part want these companies to decarbonize. The second is made up of shareholders, who by and large want the same profits and dividends they’ve always wanted. They’re deeply suspicious of forays into uncharted waters, especially when many of these companies have not shown a particularly good track record of making high returns even on their core business. (Customers are, in theory, a third constituency, but in reality have little choice in the matter — they have to buy energy, whatever happens, and however it’s produced.)

The U.S. and European majors differ, however, in the degree to which they respond to either constituency. The Europeans were faster to set carbon reduction targets and articulate what a post-carbon business model might entail, venturing from fossil fuels into renewable electricity generation. The U.S. companies’ “low-carbon” investments have stuck mostly to technologies like blue hydrogen and carbon capture that will allow them to keep selling oil and gas in a way that ostensibly produces fewer CO2 emissions, and can deliver higher returns than wind and solar.

Neither group is winning any fans among climate activists no matter what they do, short of taking down their shingle. And it’s obvious which strategy shareholders prefer: Exxon and Chevron shares trade at about twice the multiple of projected earnings than shares of BP and Shell. That differential has even raised the possibility that the U.S. companies could acquire their European rivals. Immediately after its strategy pivot was announced this week, BP’s stock price jumped 7.5%. With stats like these, no CEO of a publicly-traded oil and gas company can push too hard on climate.

With some exceptions — Exxon’s bet on offshore drilling in Guyana, for example — the companies are holding back on big-ticket fossil fuel projects as they wait to see how the energy transition shakes out.

At the same time, the European companies that rushed most eagerly into that transition, especially BP and Shell, now seem to be getting cold feet. BP walked back by half its target to reduce the carbon footprint of its products, now aiming for a 20-30% reduction below 2019 levels by 2030 rather than 35-40%.

The CEOs of both companies complained in recent days about the low rate of return on their investments in renewables, and said that ultimately they have to serve the energy market of today. And based on oil and gas prices, that market is thirsty for more fossil fuels.

Quotable

“There’s no way to think we can make the transition by cutting the supply of oil and gas. If we do, the price goes through the roof and everybody will complain,” he said. “But it’s not true that you can’t combine both being very profitable in the hydrocarbon business and preparing for the future.”

— Total CEO Patrick Pouyanné, speaking at the Atlantic Council on Thursday. His company is aiming for half the energy it produces in 2050 to be renewable electricity. Total invested $4 billion in low-carbon projects in 2022, more than its peers, and received the highest rate of return across all investments among the five majors, at 28%.

Room for Disagreement

More years of tight oil and gas markets and high profits are likely, since the industry as a whole has underinvested in production during the last decade and can’t respond quickly to short-term price signals. But longer-term, it faces an inevitable decline in fossil fuel demand, plus mounting pressure from the net-zero targets of governments and financial institutions. Sooner or later, oil and gas companies will have to learn how to live in a low carbon world, and so far none of the majors have scrapped their mid-century carbon goals.

In other words, they can’t afford to give up on climate. But the longer they wait to make the inevitable pivot, the more expensive and disruptive it will become — or, by 2050, the companies that juiced the most profit out of oil’s dying days may follow it into history.

One way to solve the problem of low returns on low carbon investments is to turn to government funding. The U.S. Department of Energy, for example, has hundreds of billions of dollars of lending capacity specifically earmarked for projects to replace fossil fuels, which oil and gas companies could tap and then get a higher rate of return on the portion they pay for out-of-pocket.

Another solution is to stop trying to make fossil fuels and renewables happen under one roof. In this scenario, shareholders who want high-risk-high-reward fossil fuel returns can keep their shares in the legacy companies, while spinoffs can cater to those who prefer the low-risk-low-rewards of clean energy. “I’m not sure they can ever really make the transition happen within their existing organizational structure,” said Michael Liebreich, the former CEO of BloombergNEF who has advised Shell and Equinor among others.

The View From Spain

One major that’s had success with the transition is Repsol in Spain, which in 2019 was the first oil and gas company to set a 2050 net- zero goal. In June 2022, it sold a 25% stake in its renewables business to French and Swiss investors for nearly $1 billion, and has taken double-digit returns by selling off pieces of other individual large-scale renewables projects.

“They’ve been rotating assets to beef up their returns,” said Tom Ellacott, senior vice president of corporate research at the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. Repsol’s 2022 earnings will come out after next week, which will give a clearer picture of how that’s working out for them.

Notable

- Shell’s waffling on clean energy goes back to the late 1990s. In a great deep dive this week, Bloomberg looks at how the company’s strategy and the world it operates in have changed since then, and whether a fundamental change in its business model may finally be possible.