The News

LAGOS — Nigerian nurses are protesting new rules to prevent them working abroad for two years after completing their training — a rule imposed by authorities trying to stop the exodus of medical talent being mirrored across the continent.

Hundreds of nurses have picketed the health regulator’s offices in Abuja and Lagos in recent days, demanding the withdrawal of the policy announced last week and due to take effect in March.

Governments across Africa are trying to tackle the problem of losing nurses and doctors who leave for jobs overseas that may pay as much as 50 times more. Several African countries — including Zimbabwe, Zambia and Rwanda — are on a list of 53 poorer nations whose loss of medical staff in this way has made their health systems vulnerable with fewer than the global median of 49 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 people.

It takes at least three years to complete nursing training in Nigeria. Under the new rules, newly qualified nurses must work in Nigeria for two years before they can apply for their licenses to be verified for use abroad.

The verification process, which typically lasted two weeks, will now take a minimum of six months, the nursing and midwifery regulatory council said on Feb. 7. It also requires a character reference letter from employers, which nurses say could unduly empower superiors.

Know More

Entry level nurses in the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) start with a £28,407 ($35,660) annual salary. By contrast, a well-paying nursing job in Nigeria may offer 150,000 naira ($100) monthly but even that is typically a scarce government job or in a specialized private facility. It is more common to find offers around Nigeria’s minimum wage of 30,000 naira ($20), nurses say.

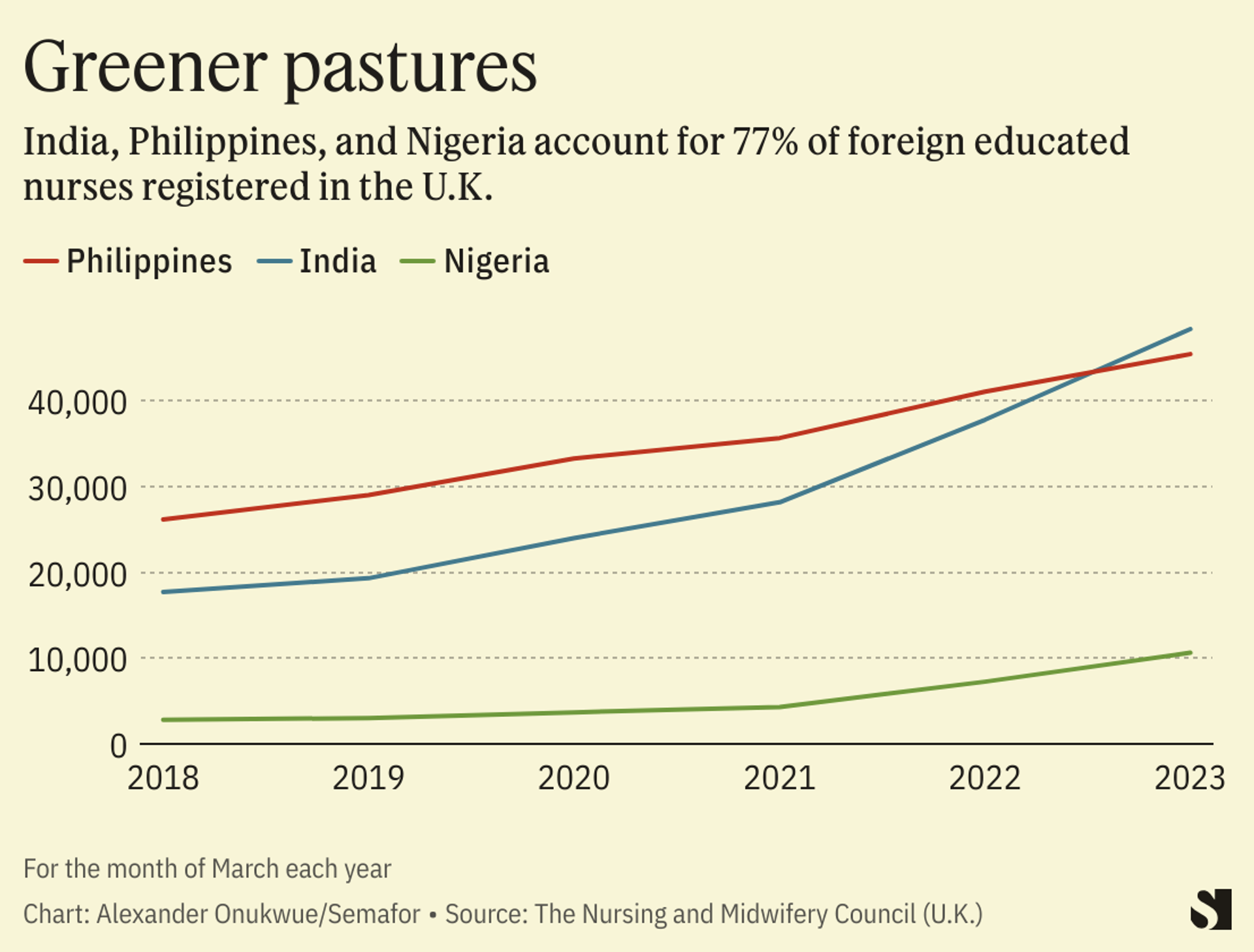

Nigeria had 1.6 nurses and midwives per thousand people three years ago, according to the World Bank. Meanwhile, data from Britain’s nursing council regulatory body shows a surge in the number of Nigeria-educated nurses in the U.K. over recent years. They nearly quadrupled to 10,639 between March 2018 and last year, the body’s data shows. Only India and the Philippines had more foreign educated nurses in the U.K. within the period.

But the data does not imply a shortage of nurses in Nigeria, says Lee Crawfurd, a research fellow at the Center of Global Development in London.

The possibility for migration can be an important incentive for local enrollments, “so taking away that option is going to make people less likely to want to train to be nurses in the first place,” he told Semafor Africa. He pointed to a study that found increased enrollment in the Philippines in response to increased demand in the U.S. and revised visa rules.

The National Association of Nigeria Nurses and Midwives, a trade union, said it has conveyed its members’ opposition to the nursing regulator. “It has been resolved and very soon we’ll make a statement,” a person close to the discussions told Semafor Africa on Wednesday, requesting anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the media. They said the policy will likely not take effect as published and the union has not pushed for a strike, though some protesters have threatened one.

Alexander’s view

The nurses’ revolt is lively evidence of deep anxiety among young Nigerian workers trying to figure out a future away from the soaring hardship in the country. Doubtful of the government’s intention to solve their problems, they are vigorously defending the freedom to ‘japa’ — literally to flee — as being as fundamental as the right to life.

In the 12 months since the last presidential elections, which were closely followed by the birth of Bola Tinubu’s administration, rising inflation and an accelerated depreciation of the naira currency have sparked a cost of living crisis. For some nurses, these conditions which have persisted for years prompt a search for options elsewhere.

Inem Etuk, 28, started working as a nurse in Nigeria in 2018 on a 25,000 naira ($16) a month salary. But despite seeing that increase four-fold after different jobs in three cities, she left for Canada two years ago even at the steep cost of 35,000 Canadian dollars ($26,000) for university fees and travel costs. “I just felt nursing in Nigeria wasn’t progressing,” Etuk, who said she was laughed at for wanting to be a forensic nurse in Nigeria, told me.

She hopes this week’s protests will amplify a need for reform, which should include plugging loopholes that allow the prevalence of unqualified nurses who work informally, driving down pay at hospitals. If authorities “address welfare issues, especially low pay of nurses,” the desire to leave Nigeria will reduce drastically, said Oluwadamilare Akingbade, a postdoctoral nursing researcher at the University of Alberta who left Nigeria four years ago.

Room for Disagreement

Faruk Abubakar, registrar of the nursing regulator, estimates that over 42,000 nurses have left in the last three years. He said the trend undermines the country’s ability to care for itself. “If we allow every Nigerian to leave as they graduate, who is going to provide our healthcare services,” Abubakar said in defense of the new rules on Tuesday.

The policy is also necessary to check what he said is a trend in which some Nigerian nurses present fake documentation abroad. British authorities are investigating a scheme involving 700 nurses who allegedly used mercenaries to pass tests in Nigeria in order to get NHS jobs.

The View From Ghana

Ghana implemented a contract in the early 2000s that required it to employ nurses trained at government-subsidized schools. Nurses who wanted to practice abroad would pay to offset their tuition fees. But the government scrapped the system seven years ago to relieve itself of the obligation to employ its nurses, given a growing backlog of unemployed nurses over time. The approach was therefore “counterproductive,” Anthony Nsiah-Asare, a presidency spokesperson on health, told Semafor Africa.

“We cannot compete with the Western countries, salary wise,” said Nsiah-Asare. “People go there for better remuneration, and that is what we are facing. And it’s not only in Ghana. Nigeria is facing it. All the lower income economies and developing countries are facing it.”

Ghana still requires nurses trained in public schools to work for at least three years and get an employer’s reference — or pay off tuition — before verification. Perpetual Ofori-Ampofo, head of Ghana’s trade union of nurses, says the policy helps keep track of the country’s roughly 93,000 local nurses. “If the taxpayers’ money has been used to subsidize your training, you should have that moral conscience to work for the good people of Ghana,” she told Semafor Africa.

— Additional reporting by Nana Oye Ankrah, in Accra

Notable

- A Kenyan cabinet official this week defended the government’s plan to send healthcare workers abroad, citing a surplus in the country. Mary Muthoni, principal secretary in the health ministry, said Kenya “cannot talk about draining human resources from the country when we are still producing and even overproducing.” Kenya will send 20,000 nurses to U.K. hospitals by 2025 as part of a health partnership agreement, the Nairobi-based NTV channel reports. It follows a 2021 bilateral agreement by the immediate past Uhuru Kenyatta government to send unemployed Kenyan health workers to Britain.