The News

ACCRA, Ghana — Ghana aims to process its iron ore locally by 2027 for steel production to boost economic growth, a government document seen by Semafor Africa shows. It is part of a continent-wide push to add more value to natural resources at home.

The goal is stated in a report by the industry regulator Ghana-Integrated Iron and Steel Development Corporation (GIISDEC), together with the Ghana Geological Survey Authority (GGSA) mineral resources body. The document shows the government has signed agreements with eight companies to assess the country’s iron ore deposits. It also shows that none of the investors currently exploring the mineral will own concessions but rather mine within a fixed term, with the government prioritizing Ghanaian companies as key industry players.

Nasurulai Abdullai, GIISDEC’s spokesman, told Semafor Africa authorities are in talks with other companies in addition to those that had already signed agreements.

The decision not to export the mineral in its raw form comes as the West African nation — the world’s second largest cocoa exporter — seeks to diversify its economy from its reliance on exports of that crop, as well as gold and oil.

“Value addition means creating employment, expanding the base of what you have and therefore creating a future that would be beneficial to the country,” Deputy mining minister George Mireku Duker told Semafor Africa.

Know More

The deposits are estimated to have an average grade of 36% — but that’s far below the premium grade of 52% — 65%. Lower-grade ores contain more impurities, making them less energy efficient to process, with more carbon being emitted than with purer varieties.

The tonnage and commercial value of the deposits are yet to be determined. As exploration continues, only one site in the west of the country — is estimated to possess a higher grade of 55%, according to the GGSA.

Nana Oye’s view

Ghana’s plans for iron ore processing are part of the country’s push to take advantage of its natural resources to grow its economy instead of exporting raw materials. In the case of iron ore, the thinking is that making steel domestically will literally provide the building blocks for international development while also creating jobs.

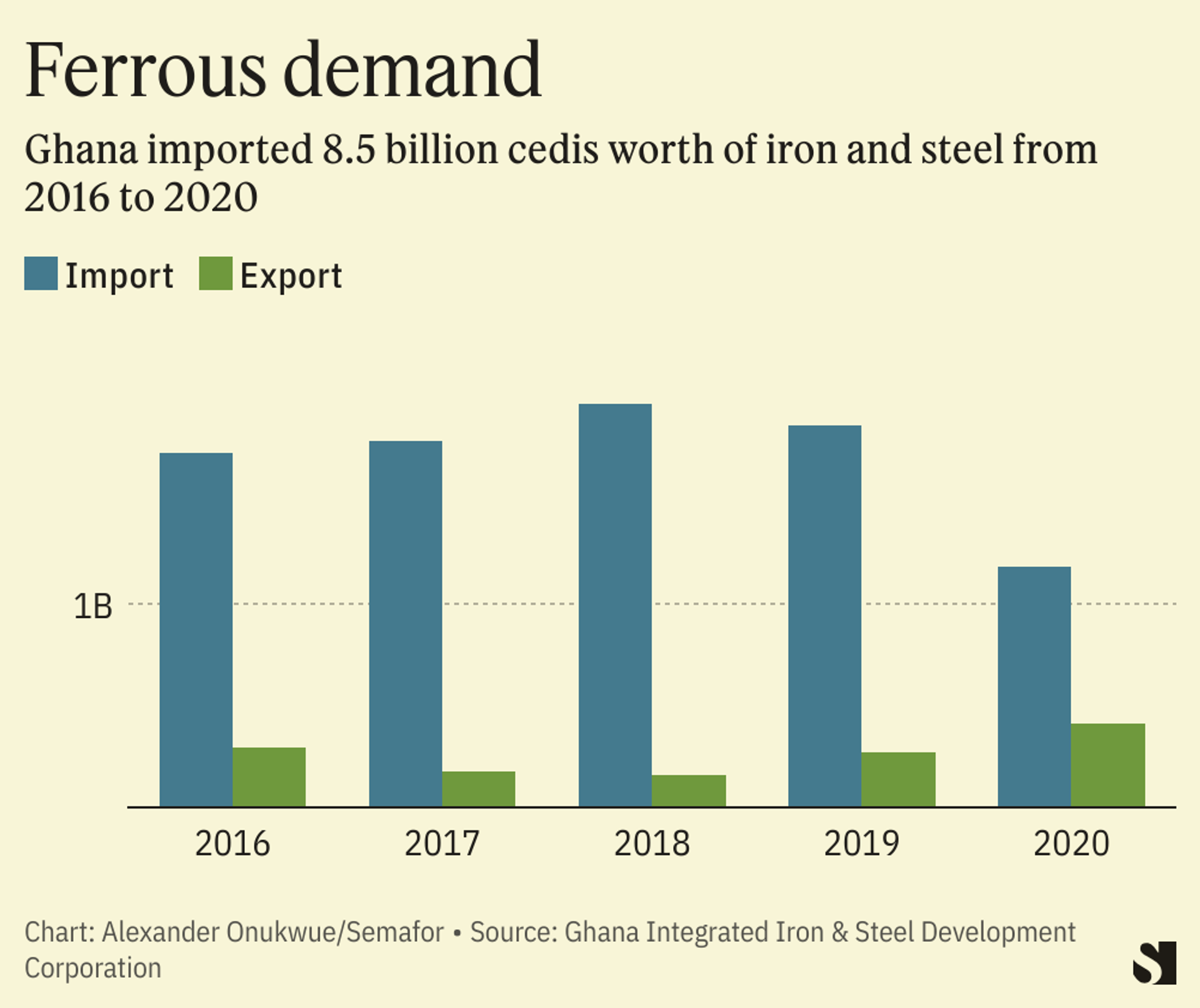

The export of processed iron would also generate much needed dollar revenues while reducing Ghana’s reliance on imports.

“If you look at the demand for iron globally, there is no doubt that we will be able to sell and this will contribute immensely to the development agenda of the country,” said Duker.

Iron ore isn’t an isolated case. Ghanaian authorities seem determined to learn from the legacy of colonialism, when gold was mined and exported without benefiting locals, and the more recent problems around illegal gold mining, also known as “galamsey,” which doesn’t benefit the public purse. Last August, Nana Akufo-Addo’s government approved a green minerals policy aimed at ensuring that the country benefits as much as possible from the production of rare earth metals that are key ingredients in electric vehicle batteries. And in October the government approved the country’s first lithium mine in a deal that will see the development of a lithium processing plant in the country.

Several African countries are increasingly trying to process minerals at home — largely spurred on by the hope of tapping into the multibillion-dollar industry around electric vehicles. Africa Finance Corporation, a multilateral lender focused on infrastructure development, this month signed an expression of interest to provide $100 million in financing to develop a cobalt sulphate refinery in Zambia by the end of 2025. The substance is used in lithium-ion batteries. Zimbabwe last year banned raw lithium exports and encouraged local processing. Similarly, the Democratic Republic of Congo has said it wants to move up the battery supply chain by processing more minerals locally.

The goals of these governments will have to withstand negotiations with companies that offer the necessary expertise as well as the rigors of domestic politics. One of those realities, which we’ll watch play out in Ghana, is the fact that Akufo-Addo’s administration will be replaced after an election in December. And, of course, we don’t know which policies will be carried on by the next government. Throw in the fact that mining is notoriously tricky, often beset by delays, and it seems hard to predict how much of the stated plan will be rolled out.

Room for Disagreement

Steel production is a huge pollutant that is responsible for around 7% of global carbon emissions.

Kwabena Ata Mensah, a minerals exploration and resource governance consultant, warned that the relatively low grade nature of Ghana’s iron ore meant processing could lead to release of far higher carbon emissions than a high-grade equivalent.

“It is a must to add value, but we have to use green and eco-friendly methods such as solar. Because we can’t ignore the consequences,” he said.

The View From Cameroon

Fuh Calistus Gentry, Cameroon’s interim minister of mines, industries, and technological development, announced last month that the country plans to become a net exporter of iron ore this year.

“We have negotiated a huge project, which will involve 100 million tons of iron ore,” Gentry told reporters in Yaounde earlier this month. “We are from 2024 a mining nation... we are going to see a regional explosion of the industry,” he said, adding that Cameroon is keen to work with China to tap its resources.

Notable

- A $20 billion iron ore project is set to start this year in Guinea’s Simandou mountains after 27 years of delays. Rio Tinto, the Guinean government and at least seven other companies — including five from China — are partnering to work on what is widely considered to be the world’s biggest mining project.