The News

Nigeria’s interest rate hike this week was broadly received by economists as a necessary move and a starting point for further increases if the country is to tame its runaway inflation. But residents may wait many months for the policy to cool ongoing cost of living difficulties, analysts say.

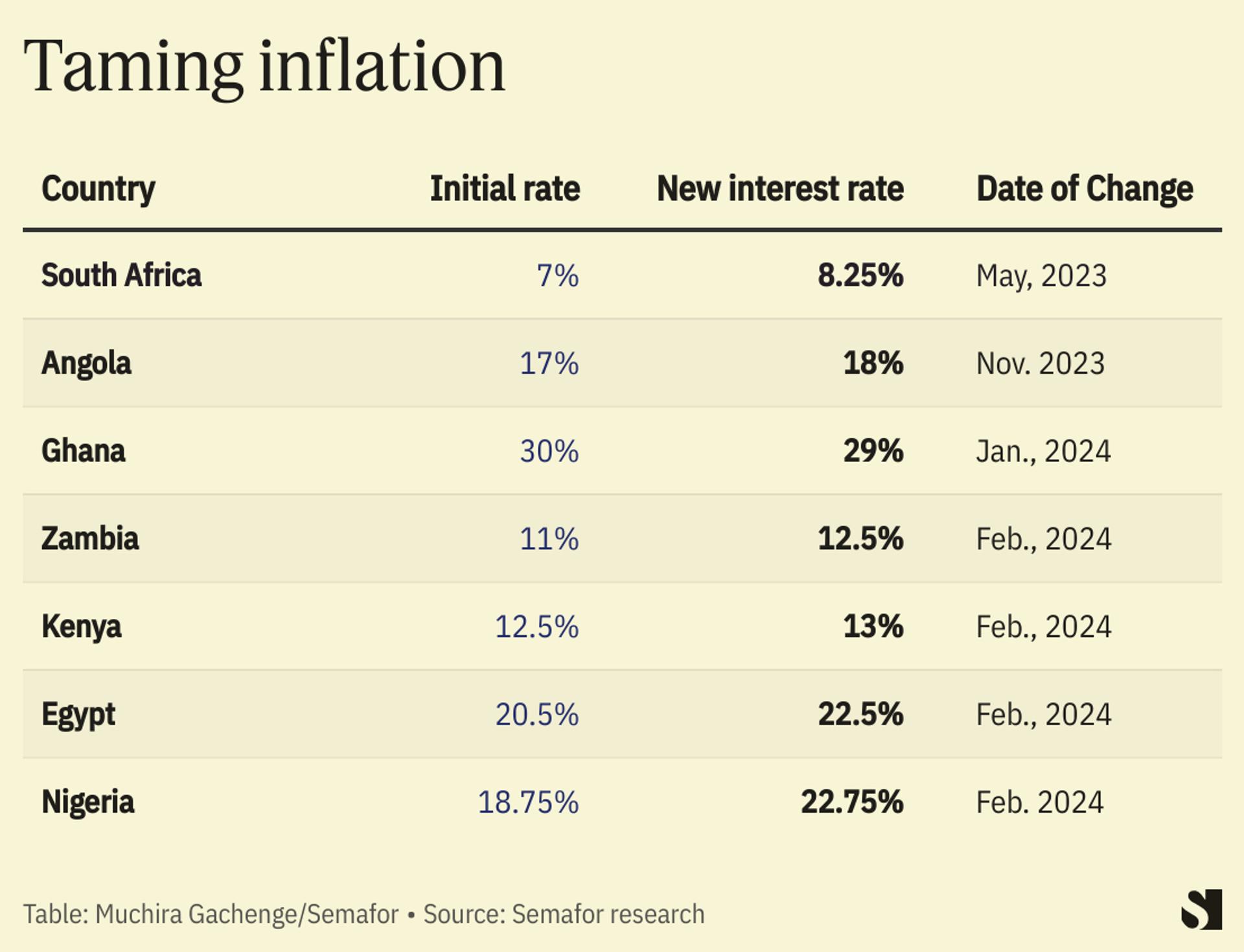

The Nigerian central bank’s monetary policy committee raised the main lending rate by 4 percentage points to 22.75% on Tuesday, at its first meeting and rate review since July. It is Nigeria’s highest increase in 17 years, according to Reuters.

The rate decision could “help catalyze some foreign portfolio investments,” JP Morgan forecasts. Nigeria is the latest African country to hike interest rates in an attempt to tame the rapidly rising cost of living. But analysts warn that certain attributes of sub-Saharan African economies should temper expectations around the impact of interest rate rises on price stability.

In this article:

Know More

Faced with inflation problems, Kenya increased its lending rate in February with a 50 basis point bump that surprised analysts who expected the central bank to leave the rate unchanged. The statistics agency said inflation for February stood at 6.3% — the lowest since March 2022, thanks to reduced food prices.

But “the consensus is that monetary policy transmission is not as strong in its influence on prices” in Africa as it is in other emerging economies, said David Omojomolo, of Capital Economics, reflecting a view shared by other analysts. One major reason, he said, is that the financial sector is usually not the predominant pillar of the overall economy.

In developed markets, high levels of private sector debt from mortgages or other loans mean interest rate tweaks are felt immediately. “So high rates hurt us, and stop us borrowing, and low rates make us over-excited, like children on Christmas Day, because debt becomes nearly cost-free,” said Charlie Robertson, head of macro strategy at FIM Partners. Interest rates do not exert a similar effect on people in sub-Saharan Africa with “virtually no private sector debt” nor mortgages, he said.

Like Kenya, Nigeria’s current inflation is significantly driven by food prices. The contribution of food to overall inflation is 52% in Nigeria, which is in stark contrast to the U.S. and Japan where its contribution ranges from 7% to 19% respectively. Food price increases in Nigeria are tied to a number of factors, particularly insecurity in the country’s food producing regions, road transportation costs tied to higher fuel prices, and a scarcity of dollars for imports. Prices will remain high overall as long as those issues remain unresolved, analysts say.

“We are cautiously optimistic that the changes at the CBN (Central Bank of Nigeria) will improve Nigeria’s inflationary prospects, but still expect inflation to average above 30% in 2024,” said Pieter Scribante, of Oxford Economics Africa.

Room for Disagreement

Cardinal Stone, a broker and investment management firm in Lagos, expects Nigeria’s rate decision “to be net-positive for the banking sector” in the 2024 financial year. Nigeria’s largest banks should see increased yields on their assets by an average of 4 percentage points, the firm said on Friday.

Notable

- Only “aggressive export promotion and free floats to let markets determine currency price levels” will successfully fight the trend of rapid currency depreciation and inflation across Africa, writes Ken Opalo, an associate professor at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, in a Bloomberg article.