The News

The 8,000 oil and gas industry representatives crowded into downtown Houston this week for the world’s biggest energy conference agree on one potentially head-scratching message: Tackling climate change doesn’t mean an end to fossil fuels.

Addressing a rapt global audience at CERAWeek, one CEO after another argued that the industry has systematically underinvested in drilling over the last decade, in part because government climate policies clouded the outlook for demand. The energy shortages and price spikes that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were a cry for help from a global economy thirsty for more oil and gas, execs including Chevron’s Mike Wirth, Exxon’s Darren Woods, ConocoPhillips’ Ryan Lance, and Repsol’s Josu Imaz said — a cry they plan to respond to by boosting drilling in the U.S. and around the world.

But don’t fear, these executives insisted: The renewed push needn’t jeopardize progress toward decarbonization, because the industry is making strides on carbon capture and other technologies to reduce the greenhouse gas footprint of drilling operations and power plants. ExxonMobil executives, for example, said that in the Permian Basin, the largest U.S. oilfield, they plan to both nearly double production and eliminate operational emissions by 2030.

“Oil and gas isn’t the problem,” Liam Mallon, Exxon’s president of upstream operations, said on stage. “It’s the emissions. It’s very clear that more investment in oil and gas production is needed.”

Tim’s view

There’s a bit of magical thinking on display here that speaks to a paradox at the heart of today’s global energy market: There’s not enough oil and gas to supply the economy, and yet too much to meet climate goals.

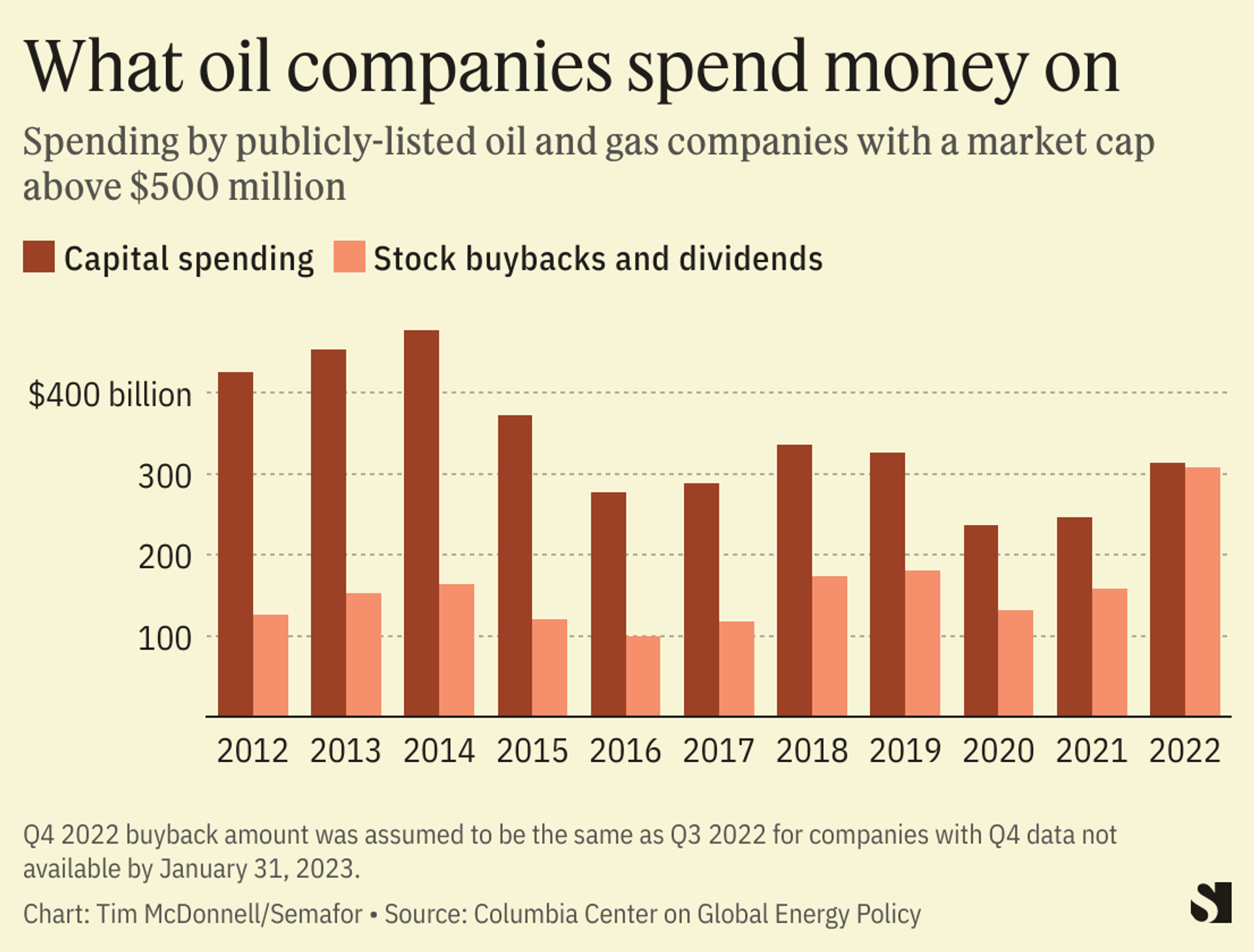

For one thing, it’s not clear that the industry’s drilling plans, regardless of climate impact, achieve its stated energy supply objectives. Current investment in production is at least $100 billion per year short of what will be needed up to 2030 to meet projected global oil and gas demand, according to a Columbia University study last week. But that shortfall is driven at least as much by the industry’s poor returns over the past decade — and the desire to placate frustrated shareholders with dividends and buybacks — as it is by concern about future climate policy, the study found.

The current demand projection, in any case, blows past the thresholds of the Paris Agreement warming goals. So even in the best realistic case for carbon capture, today’s levels of oil and gas production, let alone higher ones, are fundamentally incompatible with the world’s climate goals. The International Energy Agency made that clear in a 2021 report which concluded that to reach global net zero by 2050, there should be no further investment in new oil and gas projects.

And despite the rhetoric around low-carbon production, most oil and gas companies are spending far more on their traditional business than they are on climate solutions. Spending by the five largest oil and gas companies on low carbon projects — including renewables, hydrogen, carbon capture, and biofuels — was about 13% of total capex on average in 2022.

“Conceptually it’s right that what we care about is emissions, not hydrocarbons,” Jason Bordoff, director of Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, said in an interview. “But if you conclude from that that we can continue with business as usual on production, that’s not a real solution. Any scenario where emissions go down enough to meet our climate goals means we’re using a lot less hydrocarbons.”

Quotable

Because it provided a pretext for increased oil and gas production, the war in Ukraine “has slowed the transition down, no question about it,” said U.S. climate envoy John Kerry during a quick interview in the CERAWeek hallway. On the industry’s plans for lower-carbon drilling, he said: “If we can focus on the emissions, I think everybody can come out in a solid way and they can continue to be energy companies that are not contributing to the problem. But only if we have the ability to reduce the emissions to a level, ultimately, that’s zero.”

Room for Disagreement

To some extent, the problem is out of the hands of oil and gas executives. As long as fossil fuel demand remains high, underinvesting in production will inevitably lead to price volatility — which the public is apt to blame on climate policy. That’s why funding in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act to support renewables and electric vehicles, technologies that displace oil and gas demand, is so important.

“You have to make sure you don’t take off the existing supply before you can supply the alternative,” Amos Hochstein, a senior energy adviser to U.S. President Joe Biden, said on stage. “That friction leads to price shocks and creates political instability which erodes support for the transition.”

The View From Chevron

Chevron’s president of new energy technologies, Jeff Gustavson, said in an interview that the company is focused on biofuels, and carbon capture for oil and gas production and processing facilities, as the most readily available avenues to reduce its operational and Scope 3 emissions — those produced by the customers using the company’s products. The company expects to reduce the intensity (tons of CO2 per unit of production) of its upstream operational emissions 35% below 2016 levels by 2028. It also expects that low carbon technologies it sells to other companies will generate $1 billion in revenue by 2030.

The IRA, Gustavson said, will help make its low carbon investments more profitable, but wasn’t enough to nudge the company to do anything it wasn’t planning to do already, or set more ambitious carbon targets.

The View From Baker Hughes

For Baker Hughes, which sells services and technology to energy companies, the push for lower-carbon production is a major business opportunity. “We’ve got to stop using disdain around hydrocarbons, but make them cleaner,” CEO Lorenzo Simonelli said in an interview. Simonelli said the company is racing to roll out more hardware and software that can cut emissions from oil and gas operations, and has invested in or acquired more than a dozen smaller companies with such technologies in the last two years. The company’s revenue from its new energy offerings was less than 1% of its total in 2020, rose to 1.7% in 2022, and is expected to account for about a third of revenue by 2030.

Notable

- Contrary to concerns among conservative lawmakers, the ESG policies of financial institutions haven’t had a noticeable impact on oil and gas companies’ access to capital, the Columbia University report found. A moderate drop in financing provided by large banks over the last few years is attributable to companies asking for less, not being cut off.

Correction

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the proportion of Baker Hughes’ revenue from its new energy offerings.