The News

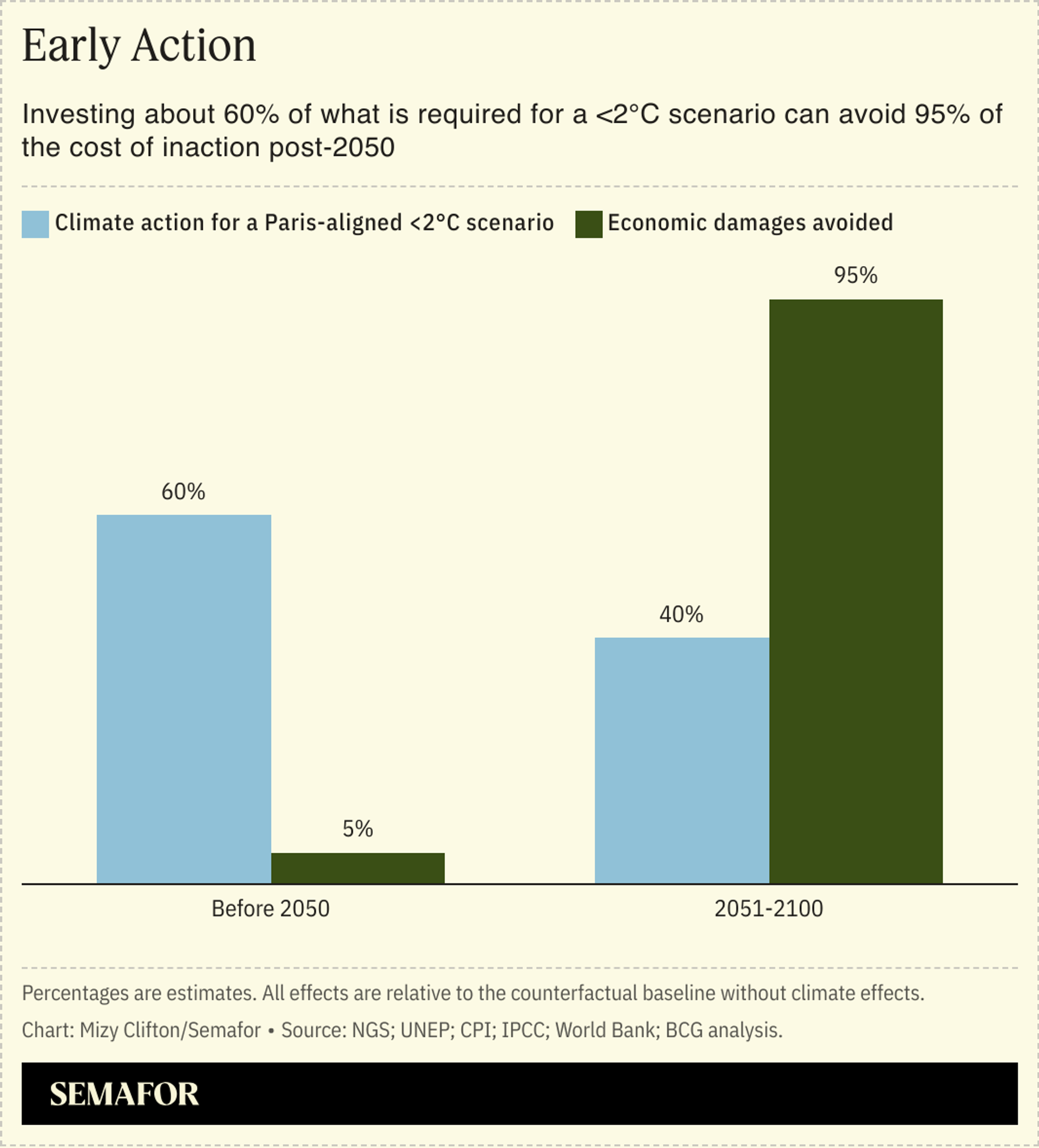

Minimizing the damage from climate change requires investments in mitigation and adaptation to increase ninefold and thirteenfold, respectively, by 2050 — equivalent to around 1% to 2% of cumulative global GDP, according to new research from the Boston Consulting Group and University of Cambridge.

The cost, though hefty, pales in comparison to the price of inaction: Climate change could reduce cumulative global GDP by up to 34% by the end of the century if the planet’s current 3°C warming trajectory continues unabated. But there are various challenges to progress, the report noted, from short-termism among leaders “who must be prepared to accept payback periods measured in decades” to lack of consensus over whether richer nations should foot more of the bill given their greater resources and historic responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions.

Still, these barriers look set to lower as climate change intensifies. For those individuals who have not been directly affected by extreme weather events, say, rising insurance premiums “may be one of the earliest signals” that climate-related risks are affecting their economic prospects, said Edmond Rhys Jones, an expert partner at BCG’s London office and co-author of the report.

In this article:

Know More

Estimates such as these are inevitably uncertain, but the magnitude of projected damages aligns with a growing body of research, Rhys Jones told Semafor.

And the case for substantial action is “even more economically compelling” if there are doubts over the feasibility of keeping warming below 2°C, he added, since initial mitigation efforts are less expensive than full decarbonization and some negative impacts are more likely to increase exponentially as temperatures rise. “It’s cheaper to avoid the first tenth of a degree than the last tenth of a degree,” he said.

The View From The UK

The relationship between decarbonisation and economic growth is an increasingly live political debate in the UK: Opposition leader Kemi Badenoch on Tuesday announced she was scrapping her Conservative Party’s commitment to net zero emissions by 2050, saying this couldn’t be achieved “without a serious drop in our living standards or bankrupting us.”

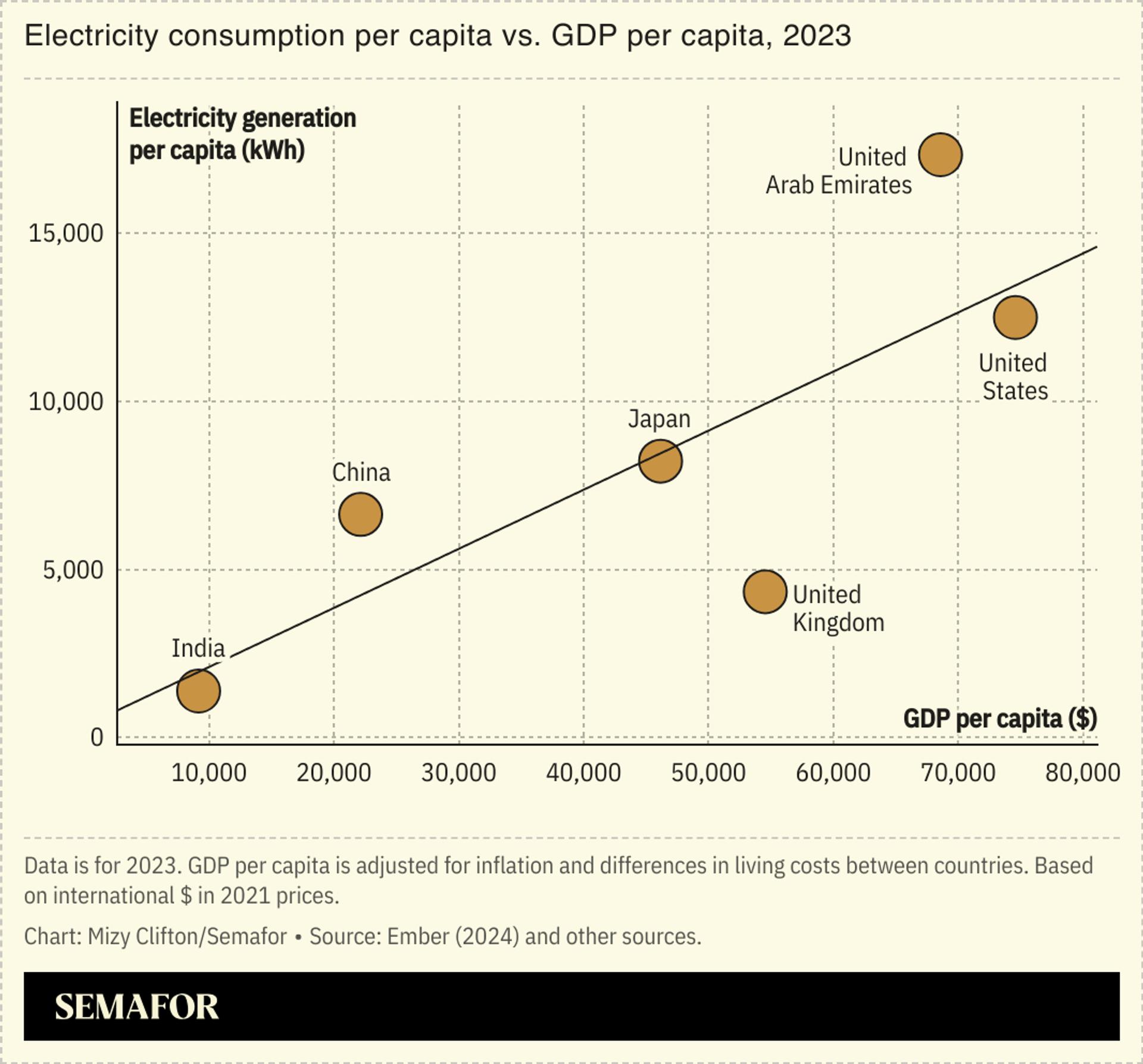

A report by London-based investment bank Peel Hunt argued this month that the UK’s lack of available additional electricity coincided with the start of weaknesses on productivity and in turn “challenges the government’s claim that there is no trade off between Net Zero and economic growth.” Energy costs will only come down — and growth pick up — if the country reduces its dependence on both imported hydrocarbons and renewables, such as by expanding exploration of domestic oil and gas fields, the authors wrote.

Yet while high electricity prices are indeed a factor likely limiting economic growth, increasing fossil fuel production would make “only a very negligible difference” to energy security because the UK has very little gas left and exports the vast majority of its oil, said Joshua Emden, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, a progressive think tank.

Besides, “the suggestion that [decarbonization] impacts growth is quite drastically wrong, because net zero industries are booming right now,” he told Semafor. A February report by the Confederation of British Industry found that the sector grew 10% between 2023 and 2024, three times faster than the overall UK economy.

These two views — on the one hand, that decarbonization limits growth prospects, and on the other hand, that climate inaction does — are not actually opposing, BCG’s Rhys Jones told Semafor.

“The key differences lie in time horizon and the individual vs. collective action lens,” he said.

Transitioning to a cleaner energy and industrial system requires significant investment, but the overall cost of decarbonisation will likely continue to decline as confidence in future deployment of green solutions improves. Companies and countries, meanwhile, can still benefit from fossil-fuel based business models, while the case for mitigation is largely a “collective action challenge,” he said.