The News

After Vice raised $500 million in 2014, its CEO and co-founder Shane Smith remarked to a friend that he’d become “post-economic.”

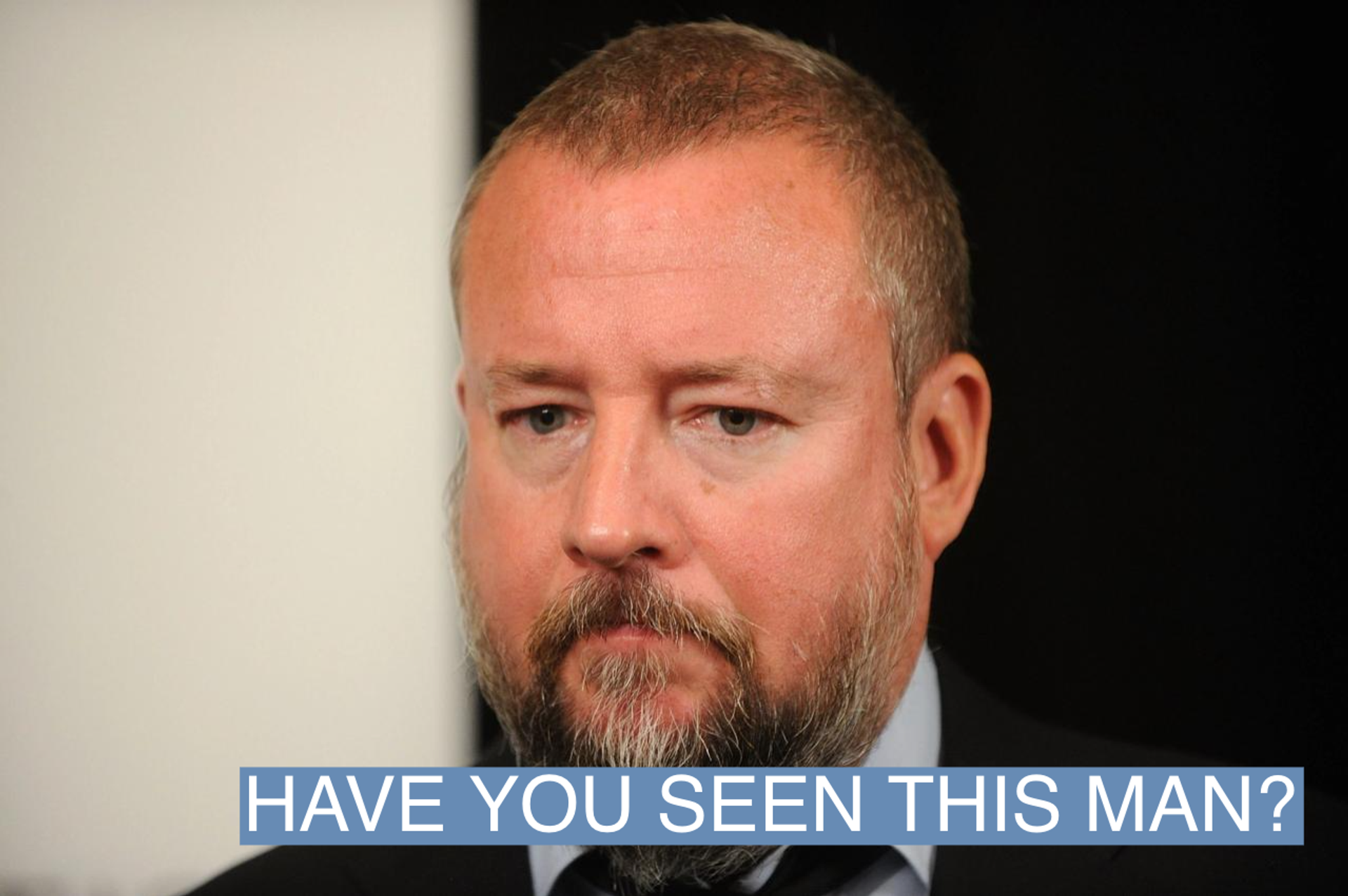

Brash, decadent, and charming, Smith was the burly, bearded face of Vice Media through its decade of apparent prosperity, from the late aughts until the late 2010s. Vice’s image as a new kind of culture business intertwined with his own image as a big new media mogul: He drove a vintage Rolls Royce, bought a mountain in Costa Rica, and reportedly dropped over $300,000 on a single Las Vegas dinner. He handed out bonuses in the form of fistfuls of (company) cash at a holiday party. He bought the $23 million Santa Monica mansion made famous by the movie Beverly Hills Cop.

But as investors sell off what’s left of Vice, it’s increasingly clear that the lavish spending helped create an illusion of prosperity.

And close watchers of the company continue to wonder: Where has Smith, who remains Vice’s executive chairman, gone? And, more to the point, how much cash did he extract from Vice?

The company remains tight-lipped on Smith’s role and his personal gains. Smith himself, once ubiquitous, has spent the last few years on a disciplined campaign to lower his own profile, and also declined to comment.

But a person with direct knowledge of the transaction revealed one remarkable detail: Smith sold more than $100 million of his own shares — about a quarter of Vice’s current value — when A&E and Crossover Ventures invested a collective $500 million in Vice in the 2014 deal that made him “post-economic.”

Vice’s change of fortune was on display last week at the South by Southwest media festival in Austin. In previous years, Vice threw wild parties featuring baby goats, pop-up roller rinks, and wild concerts with A-List rappers. This year, the company was nowhere to be found. But Smith himself was nearby: One person there told Semafor that they’d seen him in Austin, playing cards at the SoHo House.

In this article:

Max’s view

It’s understandable why Smith continues to lay low. The Vice co-founder predicted that the company would be worth $50 billion sometime in this decade, and acted accordingly, turning down the opportunity in 2015 to sell it for $3 billion to Disney. As media valuations began to turn in 2017, Vice raised another $450 million from the private equity firm TPG at a paper valuation of $5.7 billion, and didn’t reveal how much equity, if any, Smith sold.

Even when scrutiny of the dark parts of the company’s hard-partying culture and increasing pressure from investors forced Smith to relinquish his CEO title in 2018, he described himself and incoming CEO Nancy Dubuc as a “modern day Bonnie and Clyde” who were “going to take all your money.”

That prediction did not bear out. And now, the investors who believed his vision are picking up the pieces. Vice’s years-long struggle to find a buyer have pushed a company that once valued itself at nearly $6 billion to the edge of potential bankruptcy. As Semafor first reported last year, Vice has struggled to pay its bills, a situation that forced vendors to dispatch collection agencies to force the millennial-focused media company to pay up. Earlier this month, Dubuc resigned, as did global president of news & entertainment Jesse Angelo.

The core problem is that Vice was presenting what were, at best, a set of decent businesses — producing content for HBO, running an ad agency, a website, and a studio — as something novel and hazily scalable. Now Fortress Investment Group, Vice’s controlling investor, continues to field different offers for the business and its parts with the help of advisors PJT Partners and investment group Liontree.

Earlier this month, Group Black, the company aimed at increasing Black-owned-and-operated media firms, submitted a bid for Vice for $400 million, a far cry from the astronomical valuations of the past. And in recent months, Vice’s investors have canvassed potential buyers for different assets such as the women’s culture and lifestyle site Refinery29. In an interview this week with Variety, the company’s new CEOs said they were “in a process of looking at a number of options and will reflect on what we receive.”

It’s now virtually impossible that Smith, or any early Vice investors, will receive anything in exchange for their shares in the company, as Fortress’s investment will be paid back first. But equity aside, his compensation was wildly out of sync with other media founders of his generation. (Don’t shed a tear: They make the big money when their companies sell or go public). Public filings from BuzzFeed, whose valuation has also sunk since the mid 2010s, show CEO Jonah Peretti making a salary of $325,000.

Know More

Even after Smith began to lower his public profile and installed Dubuc at Vice, he retained a large and previously unreported role in the company. In the months before the pandemic, Smith still maintained an office in Vice’s Venice bureau. Two staffers told Semafor that a driver would often chauffeur him to the office in an SUV with blacked-out windows.

He also still had plenty of potential ideas for content. He was no longer the company’s swashbuckling chief correspondent, but after Anthony Bourdain died, he told staff he was interested in hosting a travel/food show in the style of Bourdain. And when Covid hit, he hosted a Vice TV pandemic interview show from his home office.

Crucially, he helped “broker” Vice’s last great deal, the rescue of Vice World News by the Saudi-backed Greek company Antenna, a person familiar with the talks said.

I spoke to nearly two dozen people who at one point interacted closely with Smith, or occupied senior levels at his company. Few had any idea how he now spends his days: When asked about some of our reporting this week, the company’s former spokesman Alex Detrick cautioned me against reporting several tidbits I’d heard from former Vice higher-ups, saying that Smith keeps in touch with just a handful of current and former executives at the company, and they likely weren’t the ones who’d talk to me.

But while he’s vanished from the day-to-day aspects of the business, he remains visible in one place: His name continues to pop up on Emmy awards submissions for Vice News productions.

Room for Disagreement

“Trust in traditional media has eroded, there are more ways than ever for our audiences to consume our content and revenue models are evolving faster than ever,” the company’s new co-CEOs wrote in a recent memo obtained by the New York Times.

Notable

- The New York Times’s Emily Steel reported in December of 2017 on sexual harassment at Vice. Smith expressed “extreme regret,” but the story diminished his ability to serve as the face of the company

- Vice Media was “built on a bluff,” Reeves Wiedeman wrote in June of 2018 in New York Magazine, noting that the tough terms of the TPG investment could turn it for Smith into “the worst deal he ever landed.”

- The company is now living on a loan from Fortress Investment Partners, the Wall Street Journal reported last month.