The Scene

ADDIS ABABA — Last month, in a post on X (formerly Twitter), I made an open offer. I called for anyone to send me a private message if they knew someone who urgently needed essential medicine to be brought from Kenya. I was set to attend the African Media Festival in Nairobi.

I was overwhelmed. Among many, I received requests for medicine for all kinds of chronic illness ranging from cancer to diabetes, as well as insulin and over the counter pain medications that are readily available in Kenya, but not in Ethiopia.

I was able to assist about half of the nearly two dozen people who approached me on social media with requests. I knew none of them, beyond exchanging a few messages on social media. But it was clear that many were desperate to help themselves or loved ones. It cost a total of approximately $500.

To help me expand my reach, I was financially supported by someone I met through a direct message on X who works with one of the international organizations based in Addis Ababa who volunteered to partially cover the cost.

I heard from people from all walks of life: rural and urban, young and old, rich and poor, and those in between. They narrated how difficult it has become to obtain basic healthcare in Ethiopia, amid a biting shortage of essential medicines.

To me, these are a small glimpse of many who are suffering in silence where potentially lifesaving basic medicine is a far-fetched dream for many.

In this article:

Know More

Ethiopia, like many African countries, has a high dependence on imports to maintain its medical supply chain. It is currently grappling with a chronic foreign currency deficit which has made it hard to secure the dollars needed to import goods.

There is a real fear that the situation could get worse. Earlier this year it was reported that the National Bank had less than $1 billion in its reserves to facilitate imports — enough for just under a month of imports — prolonging the shortage of forex to pharmaceutical imports. Reuters, citing sources, in December reported that Ethiopia only had enough import cover for far less than a month.

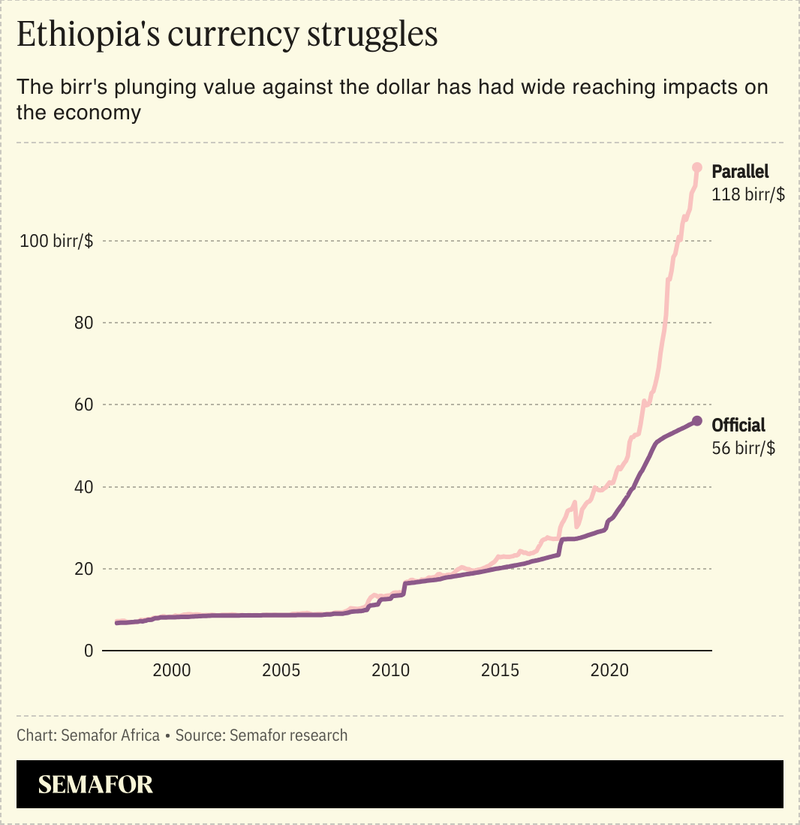

The situation has forced many importers to rely on contraband medicines. The prices are exorbitant since they are based on the black market currency exchange rate that is trading double the official rate. The market is also awash with counterfeit products that are of substandard quality.

The Ethiopian government has long aspired to become a regional manufacturing hub through its fast growing industrial parks. An effort to ramp up manufacturing capabilities for the country to meet the needs of its fast growing population, instead of using dwindling reserves for importation, has now fizzled amid conflicts and an exodus of foreign investors.

Last year, the government launched ‘Let Ethiopia Produce,’ a nationwide campaign as the Ethiopian Ministry of Industry acknowledged that hundreds of companies have stopped their operations in the country.

Samuel’s view

The situation became personal to me because I witnessed the desperation firsthand. My own father’s medicines were often shipped from Canada because none of his medicines could be found within Ethiopia. In the last year, I saw my own cousin struggle to track down basic vitamin supplements, before ultimately being forced to purchase them at highly inflated prices from entrepreneurs. Most of my friends who are prescribed medicine from pharmacies can’t find the essential medicines they need.

Samson Berhane, a business analyst based in Addis Ababa, said the foreign exchange scarcity at the center of the medicine crisis is a long-standing problem in Ethiopia. “The issue stems from stagnating export earnings which have not kept up with rapidly growing imports,” Berhane told Semafor Africa. “Production costs for many essentials have risen as most are forced to obtain forex from parallel markets where exchange rates are often twice as high as official exchange rates,” he added.

I am aware that I am the exception — and so were my father and cousin. Many Ethiopians do not share such experiences. With the nation’s economy expected to worsen and dwindling foreign exchange available to a vast growing economy, many people are expected to suffer.

The View From Mekele

The shortage of medicines has been particularly acute in areas affected by conflict such as the northern Tigray region which was ravaged by the two-year civil war that ended in 2022.

Ayder Hospital, which is located in Tigray’s regional capital Mekele, was under siege for two years during the conflict. It has been crying out for assistance amid a lack of basic medicine for preventable and treatable diseases that are killing many patients.

“We’re still not getting enough medicines, medical equipment and laboratory regents”, Kibrom Gebreselassie, the chief executive director of Ayder, told Semafor Africa.

Notable

- Ethiopia is bidding to become an African medical tourism hub with a new $400 million hospital but its healthcare system is collapsing.