The Scoop

LONDON — Nigeria’s financial stability is on the line in a legal battle where its opponent is claiming payments allegedly made to secure a contract are — simultaneously — both legal and illegal.

At stake is an $11 billion award — a sum close to a third of the country’s foreign exchange reserves. An arbitration tribunal in London ruled in 2017 that Nigeria must pay $6.6 billion, which has ballooned with interest, to a company called Process and Industrial Developments (P&ID). Nigeria was adjudged to have breached a contract, awarded to P&ID in 2010 by the country’s petroleum ministry, for the construction of a gas processing plant in the southeastern city of Calabar that was never built.

Nigeria refused to pay the award and tried to get it overturned in a six-week trial this year at the English High Court during which it argued P&ID made unlawful payments to Nigerian officials to secure the original contract. The hedge fund that bought a controlling stake in P&ID, VR Capital, directed the company to argue in court that the payments were legal.

But VR Capital is arguing in a separate lawsuit that P&ID’s payments to Nigerian officials did in fact break the law, and is using that as a basis to sue the business partners it bought its stake in the company from. “Regardless of whether or not these payments were made for corrupt purposes, they were unlawful,” a division of VR Capital wrote in May 2021 in a confidential London Court of International Arbitration filing seen by Semafor Africa. “As a matter of Nigerian law, any undisclosed payments to a public official by someone seeking a government contract is prima facie unlawful.”

The payments VR Capital calls “unlawful” in its May 2021 filing are those made by companies linked to P&ID to Grace Taiga and Taofiq Tijani, two petroleum ministry officials around the time the gas contract was signed. Taiga denies any illegality. Tijani said in an affidavit before he died in 2021 that he had been bribed by P&ID.

Details of the previously confidential case between the P&ID shareholders emerged because Nigeria is seeking documents from various VR Capital companies in the U.S. The filing came to light in New York in December following a two-year long disclosure battle between the two parties.

VR Capital is “cynically pursuing” vast damages from Nigeria in open court while alleging behind closed doors that Nigeria was indeed wronged by P&ID, barrister Mark Howard, representing Nigeria, told the High Court. “The doublethink behind this position is impossible to justify,” the government added, describing the approach as “thoroughly dishonorable.”

Know More

P&ID was set up in 2006 by two Irish businessmen — Michael Quinn, a former music manager, and his business partner since the 1970s, Brendan Cahill. The company is registered in the British Virgin Islands. Quinn died in 2015 and Cahill has repeatedly denied that P&ID paid any bribes.

The company was taken over by VR Capital, a hedge fund registered in the Cayman Islands which has offices in both London and New York, following its 2017 arbitration victory over Nigeria.

The High Court is expected to make a ruling within weeks on Nigeria’s attempt to nullify the $11 billion payment.

Olivier’s view

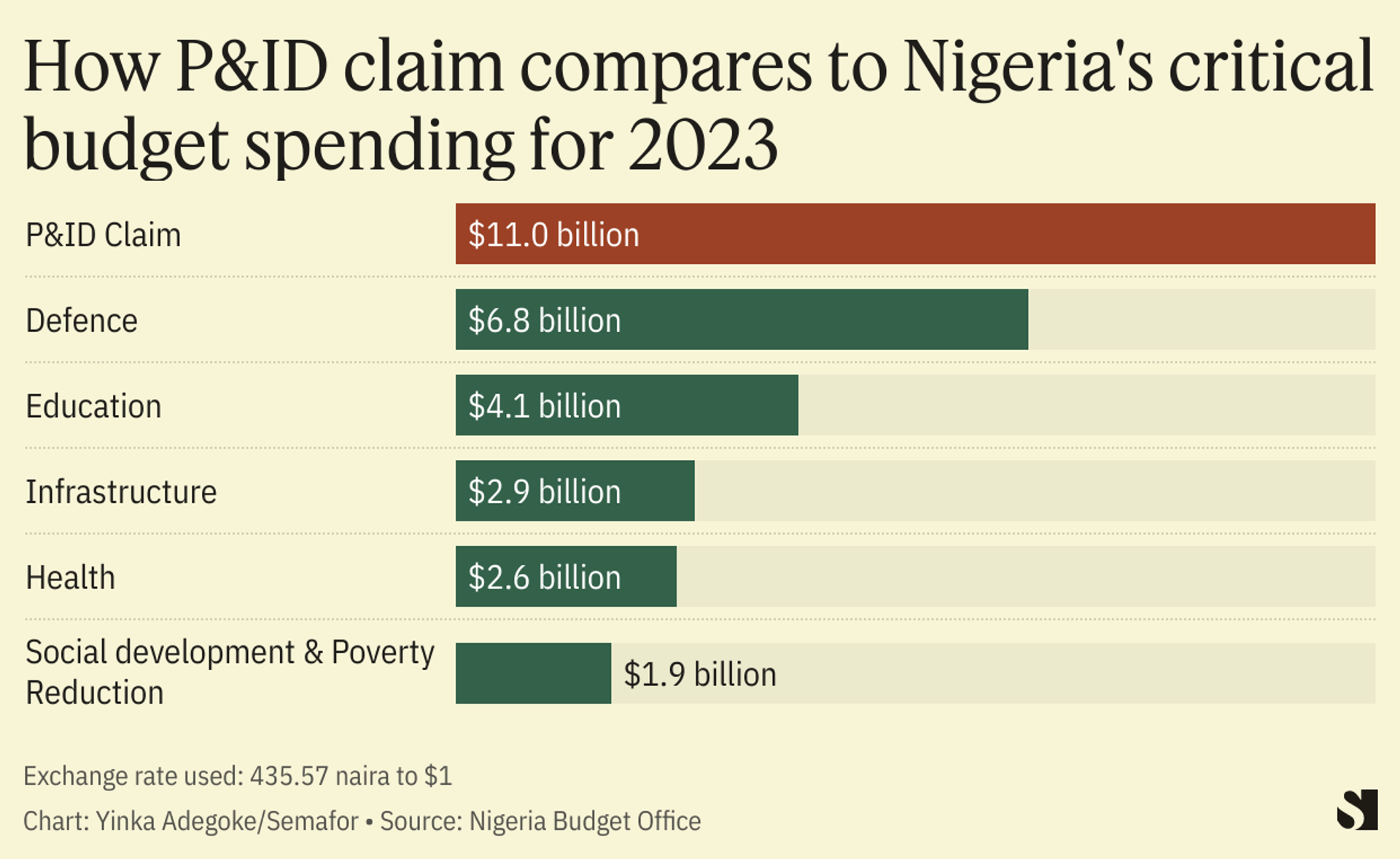

The case could have far reaching consequences in Africa’s biggest economy. A ruling that the country must pay $11 billion would be a major blow for the country’s president-elect Bola Tinubu, who is due to take office in May. It would be a huge chunk of the public purse, diverting funds away from essential public services, such as healthcare and education. Crucially, it’s nearly a third of the import-dependent economy’s foreign reserves, which stand at around $37 billion.

Nigeria’s reserves are already dwindling, largely due to a fall in oil production since crude sales bring in the bulk of foreign exchange. At the same time, U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate rises have pushed up the cost of servicing dollar-denominated loans. Other African countries, such as Ethiopia and Kenya, are already struggling with dwindling foreign exchange reserves.

It makes sense that VR Capital would seek to recoup its investment in P&ID, including through litigation, if the High Court found that P&ID had acted unlawfully. But it speaks to a level of cynicism that the hedge fund can simultaneously argue that P&ID was lawful and that it was not — possibly under the presumption that its confidential pleading would never come to light.

Room for Disagreement

At the High Court, P&ID’s barrister David Wolfson defended the conflicting pleadings, arguing that the fund owed it to its investors to pursue every avenue to recover its investment in P&ID, whether through enforcement of the award or through separate litigation if P&ID broke the law.

“It is right that VR has sought to hedge its position,” Wolfson told the High Court. “That’s what investors do.”

The View From Abuja

The gas processing plant was “extremely unusual as a proposed project,” said Fola Fagbule, deputy director and head of financial advisory services at Africa Finance Corporation, a multilateral lender focused on infrastructure projects on the continent. He said it was odd “in every respect, not least in terms of the lack of due process, proper diligence, transparency and project development that would typically be required prior to contract award for a project of that scale.”

Fagbule said it would be “catastrophic” if Nigeria was required to pay $11 billion. “It’s a sum that is staggeringly out of proportion to anything Nigeria can afford and certainly not for a scam project,” he said.

P&ID denies that the gas project was a scam.

Notable

- The secrecy that shrouds international arbitration cases is a key factor in the dispute between P&ID and Nigeria and should be reviewed, a legal expert tells the UK’s Observer newspaper as it charts the more than decade-long saga.

— With Alexis Akwagyiram