The News

Economists and policymakers will spend years dissecting what happened in the banking system over the past two weeks. But the black swan at the heart of it was a bad bet on human psychology.

Uninsured depositors in the U.S. didn’t behave the way they usually do in crises.

Current rules, even for the largest lenders, assume that only 3% of insured retail deposits, and between 5% and 10% of uninsured retail deposits, depending on what penalties apply, would be pulled out of a bank in times of stress.

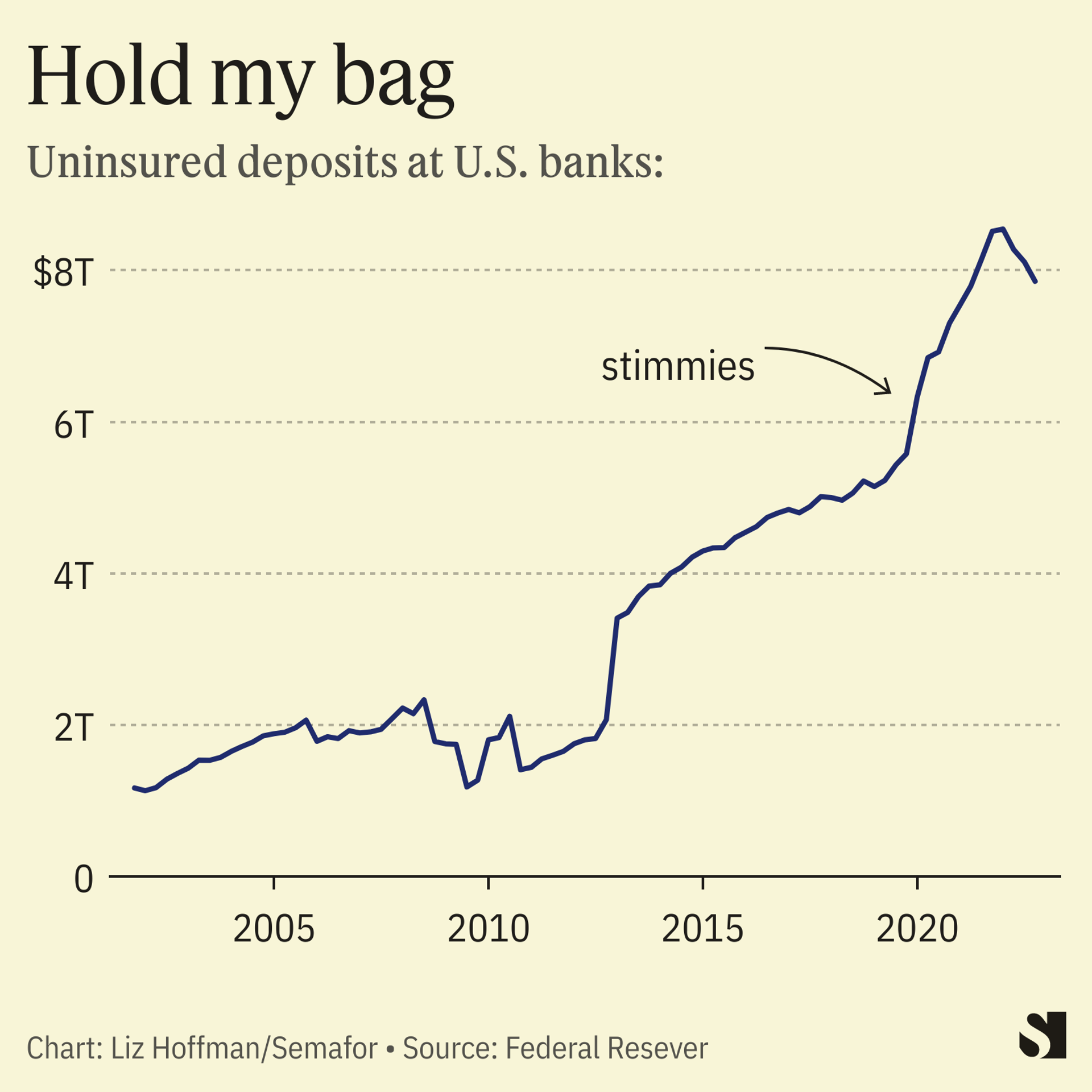

Those numbers are somewhat higher for corporate deposits like those at Silicon Valley Bank. But none of the guardrails assume near total withdrawals of deposits, and certainly not at the speed with which they have whooshed out of America’s regional banks. (Regulators usually calculate liquidity on a 30-day basis.)

“Uninsured deposits are not what we thought they were, plain and simple,” said Randal Quarles, the Fed’s vice chair of bank supervision from 2017 to 2021. “If we had known, with 50 years of supervisory experience, how flighty they would turn out to be, we’d have done things differently.”

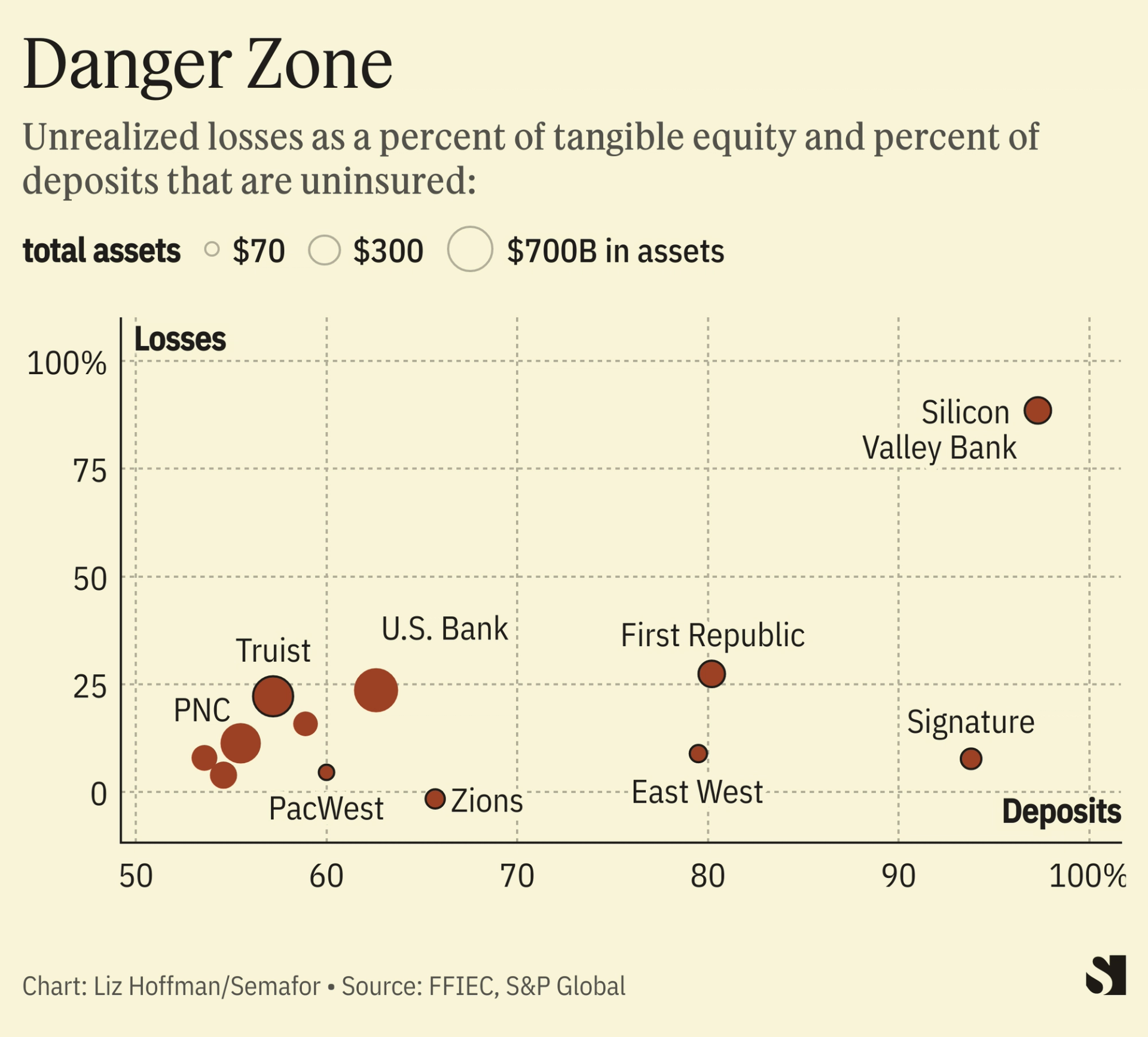

As many as 190 banks are in danger of an SVB-like run, due to a combination of unrealized losses on their investments and a high percentage of deposits that exceed the $250,000 insurance cap, according to a new study from researchers at Columbia, Stanford, Northwestern, and USC.

The paper doesn’t name at-risk banks, but here’s how some of the big regional lenders stack up on those metrics, which you can think of as the spark and the tinder that can ignite panic. Being forced to recognize previously glossed-over losses spooks depositors, especially those whose savings are uninsured, leading to a classic bank run.

The question now, Quarles said, is whether the speed at which SVB unraveled was unique, given its overreliance on a single kind of customer, startups and venture firms, who all panicked at once. That problem might be fixed by imposing limits on how much exposure banks can have to any one population.

Or “should we expect this going in a world where you can have a perfect flow of imperfect information?” he said.

Step Back

The term “black swan” comes from an old assumption that all swans were white, which held for centuries until colonizing Europeans stumbled onto Australia and found black swans among the continent’s menagerie of strange creatures.

Popularized by economist Nassim Taleb in his 2007 book, the term is now a warning: The most dangerous and costly crises come when something that has never happened before—something that everyone has assumed could never happen—happens. (Of course home prices could go down everywhere all at once.)

Liz’s view

Much has been made of whether this could have been prevented if SVB had been subject to the same rigorous stress tests as the biggest banks. When it comes to assumed stickiness of deposits, the answer is no.

With decades of data at their backs, regulators bet on people being rational, or at least being irrational more slowly than they’ve been over the past two weeks. That assumption is worth revisiting.

The deposit insurance cap should be raised, and it might be worth distinguishing mom-and-pop savings accounts from corporate cash accounts.

Retail depositors can’t be expected to be bank risk managers, and if we’re going to push that responsibility onto them, why even have banks? They exist to transform risk — that is, to take safe, overnight money like deposits and turn it into longer, riskier things like mortgages. Regulators can force them to keep a dollar in cash for each dollar they owe people, but then that’s not a bank, it’s a mattress.

And it’s easy to make fun of the venture community here for keeping all of their money at a single bank. But it’s impractical for companies to be spreading their money around to dozens of banks, and they would get worse pricing and services for doing so. Peter Conti-Brown, an associate professor at Wharton, suggests a higher cap for businesses with, say, fewer than 100 employees, which makes sense to me.

Room for Disagreement

If bank executives don’t have to treat their deposits with care, they won’t.

Ryan Kamphuis, the CEO of Bristol Morgan Bank, a small Wisconsin lender with $176 million in assets, wrote on Twitter that even Washington’s limited actions so far “are creating a two tier banking system” and punishing banks that made responsible

Even President Franklin Roosevelt, on whose watch the FDIC insurance fund was created, was against providing a government guarantee of all bank deposits. And the American Bankers Association agreed, according to one of FDIC’s own researchers, Christine M. Bradley, who wrote the group worried such a program “rewarded inept banking operations.”

And there’s already an easy solution for retail deposits that exceed the FDIC’s cap. Plenty of services like IntraFi will divide customers’ money between banks to ensure no single account exceeds $250,000.

The View From Janet Yellen

The U.S. Treasury Secretary has been sending mixed messages on whether all retail deposits are effectively guaranteed. Speaking Tuesday to the American Bankers Association, she gave what sounded like an implicit promise, urging the public to “have confidence in our banking systems” and pledging support to lenders dealing with “contagious bank runs.”

But testifying in the Senate yesterday, she said her department had not discussed “blanket insurance” for the billions in uninsured deposits at American lenders.

Notable

- The full video and transcript of Yellen’s testimony before the Senate this week.