The News

U.S. Senate Republicans are warming to an idea to fight climate change that Democrats have been pushing for years: Import taxes on high-carbon industrial commodities.

In interviews this week, several said they see a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” (CBAM) as ripe for bipartisan cooperation, and plan to introduce new Republican-drafted legislation soon. But the devil is in the details, and senators are divided both between and within party lines over how a CBAM would work, and what costs — if any — it would impose on American companies.

Tim’s view

The biggest issue dividing proponents on Capitol Hill is whether a CBAM would need to be paired with a domestic carbon tax.

A CBAM is a fee applied to certain imports — which could include steel, iron, fossil fuels, or others — pegged to the carbon emissions associated with their production in their country of origin. From a climate point of view, it aims to prevent carbon “leakage,” whereby a country essentially offshores its most carbon-intensive industries, reducing its own carbon emissions but not those of the world overall. It also protects domestic companies that face higher production costs due to climate policy, and, in principle, leverages the lure of the U.S. market to force other nations to cut their CO2 emissions.

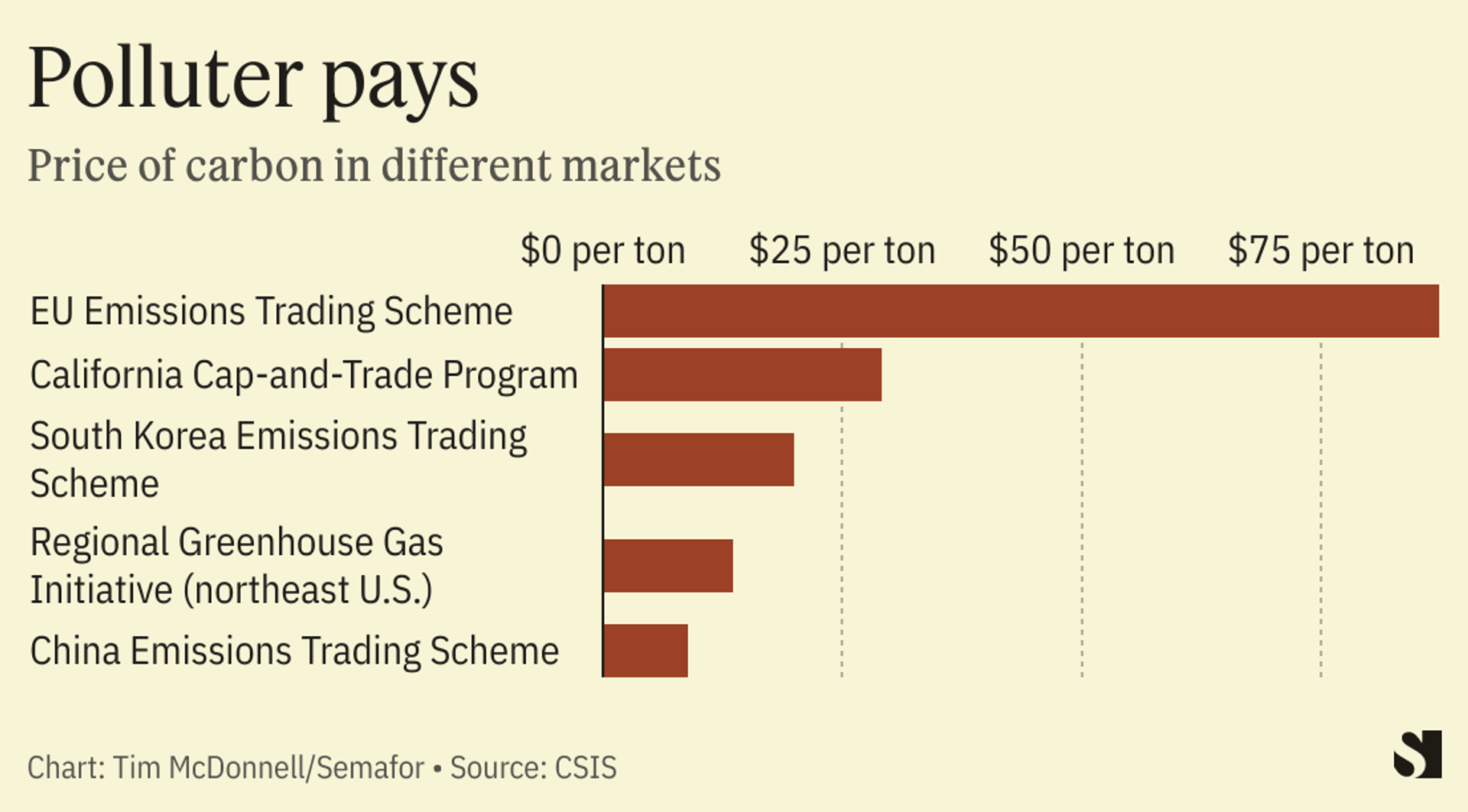

In textbook economics, and in the European Union’s version of the policy introduced last year, a CBAM only makes sense if domestic companies are also paying a price for the carbon they emit. Otherwise, such a policy could be unfairly protectionist and face legal challenges in the World Trade Organization. The U.S. doesn’t have a federal carbon tax, so it’s not clear what a CBAM could be pegged to. The range of views in Washington on this question stems from a lack of coherence on what the CBAM is meant to achieve.

Know More

CBAM legislation introduced last year by Democratic Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island would impose a limited carbon tax on companies in the fossil fuel, petrochemicals, fertilizer, iron, steel, and aluminum sectors, based on whether emissions exceed a sectoral benchmark. Pairing domestic and import carbon taxes is an idea backed by Republican Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, who told Semafor that carbon pricing is “the only real way that you can affect global emissions,” as well as the American Petroleum Institute, the main U.S. fossil-fuel lobby group, since it would be advantageous to U.S. oil and gas producers with lower operational emissions than many overseas competitors.

Separate legislation introduced in 2021 by Sen. Chris Coons, Democrat of Delaware, takes a different tack, requiring federal agencies to calculate the cost for U.S. companies to comply with federal and state climate regulations and use that figure to benchmark the CBAM against.

It’s not yet clear how forthcoming Republican legislation will address this issue. But the senators leading the drafting — including Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota, and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana — seem to agree that no new domestic tax is needed.

“I do support some form of [a CBAM] as long as it doesn’t become a domestic energy tax,” Cramer told Semafor. “We ought to be acknowledging the excellence of the American manufacturing community, [which is] already paying a lot to comply with our much stricter environmental regulations.”

That line of reasoning is contentious.

“At least at the federal level, we don’t have any meaningful climate regulations that impose costs on domestic producers,” said Noah Kaufman, a climate economist at Columbia University who worked on carbon pricing in the White House during Barack Obama’s presidency.

If those costs do exist, as a practical matter it would be difficult to apply the same analysis to compliance expenses faced in other countries, an essential criteria for determining a given import’s tax liability. Any policy not clearly matched to a domestic carbon tax would almost certainly face legal challenges in the WTO. Moreover, any estimate of compliance cost would by definition be an approximation that can’t capture the specific emissions attributes of individual facilities, said Alex Muresianu, a policy analyst at the nonprofit Tax Foundation.

Ultimately, some Republicans are more focused on how a CBAM could be used to ding trade adversaries, not solve the climate crisis per se. Cassidy’s goal, he said, was to use a “foreign pollution fee” to “address national security issues” and “level the playing field with China.”

Quotable

“For people who are sincerely concerned about greenhouse gas emissions, why wouldn’t you want to go after China and Russia, Venezuela, rather than American businesses?” — Republican Sen. Kevin Cramer.

The View From Brussels

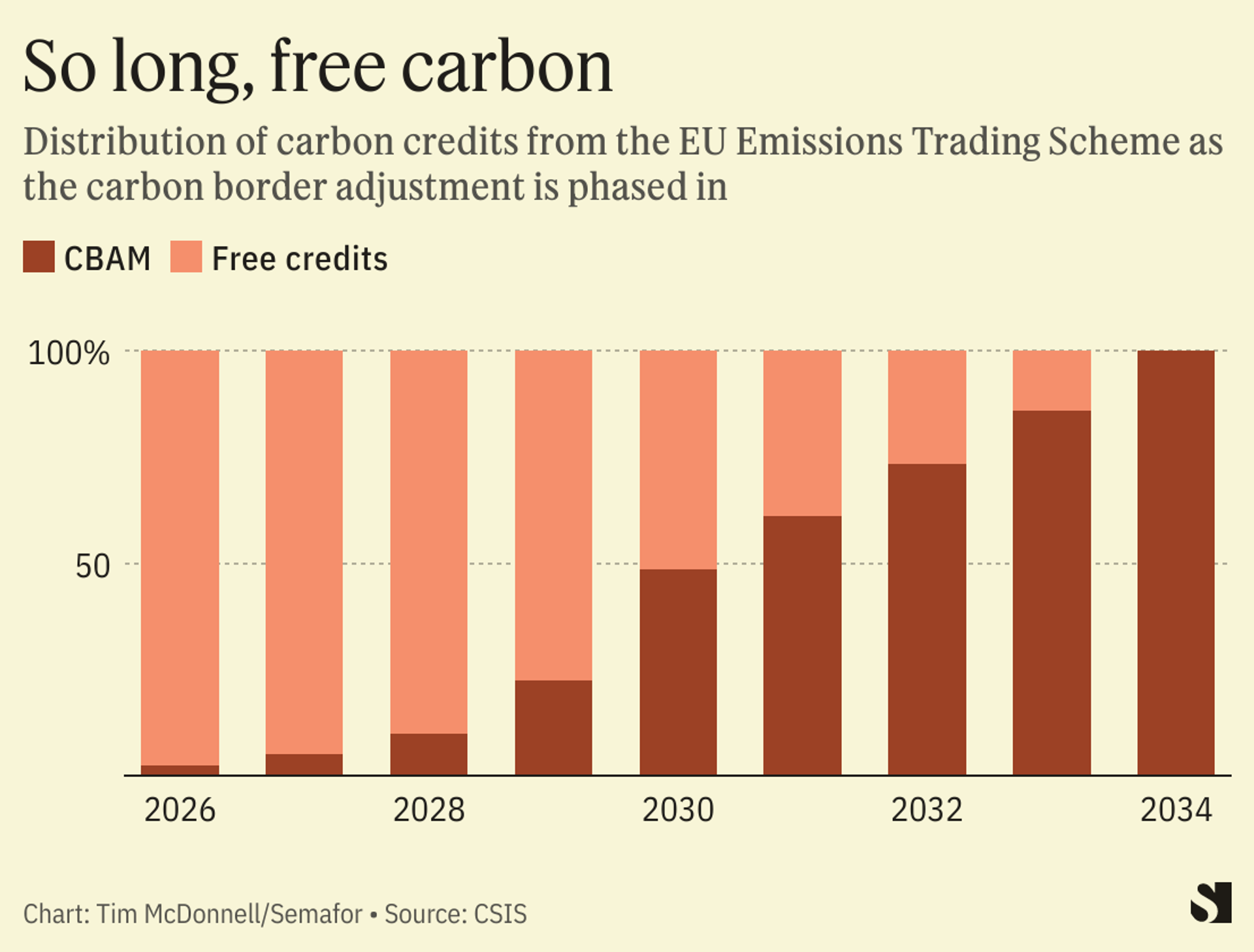

U.S. lawmakers could take a cue on domestic carbon taxation from the EU. Under the current EU carbon market, factories receive a certain number of carbon pollution allowances for free, and have to pay for excess emissions. Over the next decade, free allowances will be phased out at the same time import taxes are phased in, to maintain equity between importers and domestic producers and blunt any sudden spike in prices for domestic consumers.

The View From White House

The White House is already working on an approach to carbon trade rules that bypasses both the need for new legislation and the thorny question of carbon taxes. It is negotiating a trade “club” with the EU for steel and aluminum that would lift tariffs in exchange for shared low-carbon production standards. Countries outside the club could adopt the same standards and join, or face tariffs. A similar approach could be applied piecemeal to other sectors, but would need tailor-made diplomatic agreements in each case.

Room for Disagreement

One argument against CBAMs is that they may unnecessarily increase the cost of the energy transition by making cheaper renewable technology manufactured elsewhere more expensive. If the ultimate goal of the energy transition is to cut greenhouse gasses as fast — and as cheaply — as possible, a CBAM may make that more difficult.

Another risk with CBAMs, in general, is that they may impose costs on low- or middle-income countries that are out of step with climate-equity provisions in the Paris Agreement (although few of the world’s poorest countries are exporters of the commodities in question).

Notable

Some Republicans also think a CBAM would be more damaging to Russia’s oil and gas industry than sanctions have been. In Foreign Policy, Cramer and former U.S. national security advisor H.R. McMaster argue that “lifecycle greenhouse emissions from Russian natural gas piped to Europe, for example, are over 40 percent higher per unit of energy than U.S. shipments of liquefied natural gas.”