The News

The U.S. Department of Energy announced this week it will dole out $6 billion in grants to cut emissions from three dozen factories across a wide range of industries — including steel, cement, aluminum, even whiskey and pasta. The Biden administration’s climate strategy up to now has focused primarily on cutting emissions from the power and transportation sectors, particularly via wind and solar energy and electric vehicles. The new funding targets heavy industry, which accounts for one-third of the country’s carbon footprint but has seen much slower progress on decarbonization because the technologies involved are mostly new and have rarely been tried at commercial scale.

The combined emissions savings from all 33 projects would be equivalent to taking three million gas-fueled cars off the road, Kelly Cummins, acting director for the DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, told Semafor. And if all goes according to plan, that’s just a down payment on bigger cuts in the future.

“We want to make sure these are not just one-off projects,” she said. “The only way we’re going to meet our long-term climate goals is if we get replication from these demonstration projects.”

Tim’s view

It may be time to retire a climate cliché: Emissions from the sectors targeted in this program are sometimes called “hard to abate,” because many industrial processes require high temperatures from burning coal and natural gas that aren’t easily replaced by low-carbon electricity. But research and innovation over the past few years have delivered a range of technological solutions for high-carbon industries. Now, the biggest obstacle is getting factory owners, their customers, and their financiers to take a gamble on bringing those from the lab to commercial scale. The new round of DOE funding is meant to lower the stakes.

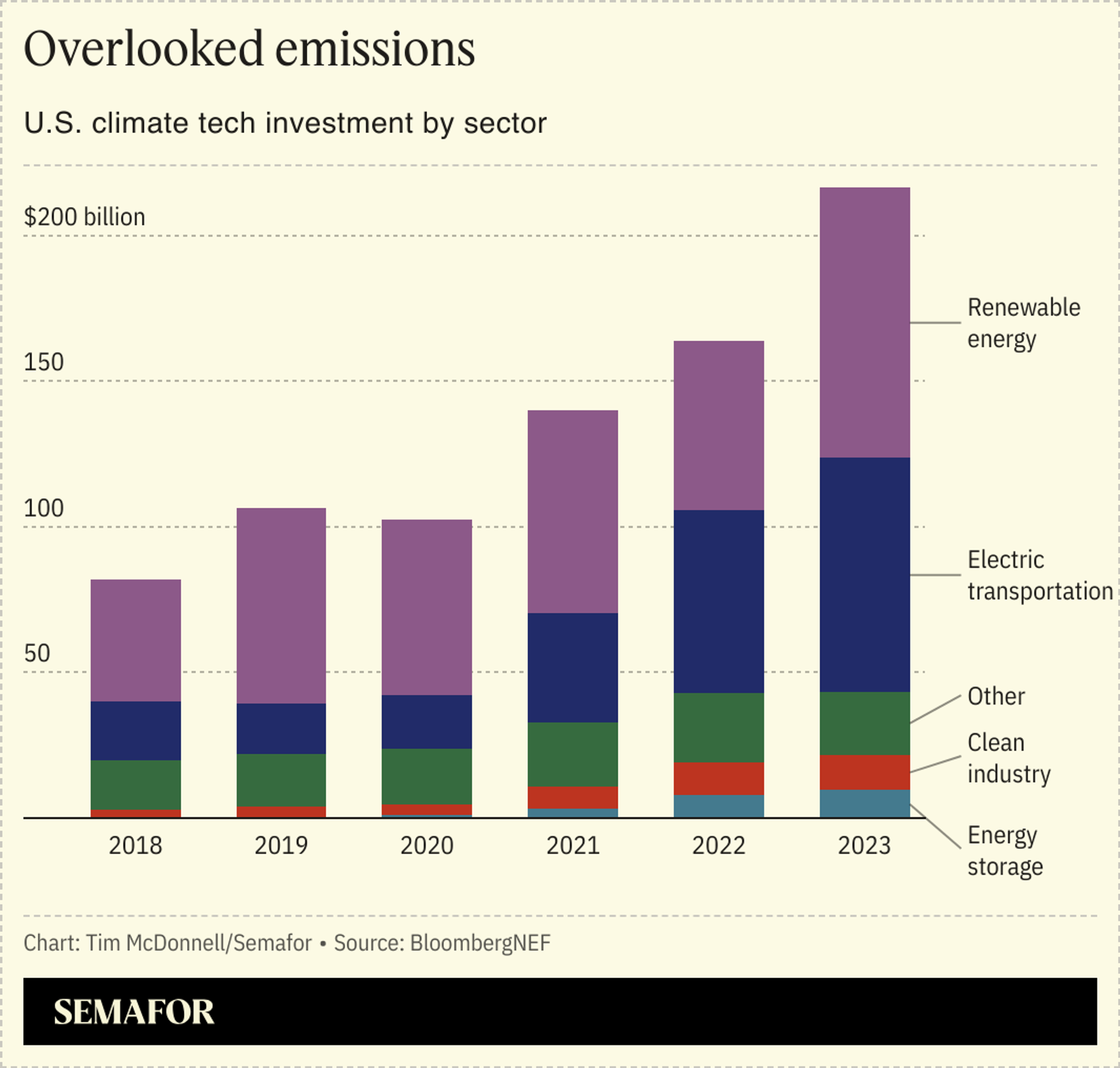

Of the roughly $811 billion invested by the private sector in climate tech since 2018, only about 5% has gone to low-carbon industrial processes, according to BloombergNEF data. Electric vehicles, by comparison, have captured 30%. For each of the projects in the DOE program, federal funding can supply no more than half of the total investment required, and in most cases much less than that, Cummins said. She expects the DOE’s $6 billion to draw in at least another $14 billion from private investors, with more to follow if the proof-of-concept works.

“We prefer ‘yet to abate’ now instead of ‘hard to abate’,” said Bryan Fisher, managing director for climate-aligned industries at the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute. “All of these are near-proven technologies that just need to be demonstrated in a commercial environment. Somebody just has to do the first one, so we can get the second and third ones.”

Projects in the program include replacing coal-burning blast furnaces at an Ohio steel plant with alternatives that run on hydrogen and electricity, a super-efficient aluminum smelter that will be the first such smelter built in the U.S. in 45 years, and a gas-electric hybrid glass furnace in California to churn out low-carbon wine bottles. Some of the grants will benefit startups working on their first-ever commercial-scale facility. Others will benefit big incumbent emitters trying to clean up, including an ExxonMobil petrochemical refinery in Texas, a steel plant run by Sweden’s SSAB, one of the world’s largest steelmakers, and an effort by beverage giant Diageo to replace gas-fired boilers used in the production of Bulleit whiskey with electric ones. Big companies like Exxon may not be obvious candidates for federal climate funding, but they have the balance sheet and technical expertise to put a major dent in emissions if they can be convinced to opt for a lower-carbon alternative, Fisher said.

To actually get a check from DOE, all of these projects have to clear a few more rounds of due diligence, including proving they’ll create local jobs and that they have at least a few early customers lined up that are willing to pay a bit more for green products. Most likely, not all of these projects will pan out. But if even a few do, the return on investment — in terms of emissions reduced per taxpayer dollar invested — would be huge.

Room for Disagreement

DOE’s domino-effect thesis — that getting a first round of projects over the financing hump will tip off a wave of private investment — is far from a surefire bet. Many of the projects here will rely on a steady supply of low-carbon hydrogen, which is practically nonexistent today. There are familiar challenges around infrastructure permitting, as well as offtake contracts: It doesn’t matter if the technology works if customers aren’t willing to pay for it. And all of this is playing out against the rapidly ticking clock of climate change. “Trying to grow infant industries is a complex, multi-decade process,” said Todd Tucker, director of industrial policy at the Roosevelt Institute. “It’s not for people who want quick results.”

The View From Oakland

One of the program’s beneficiaries is Cody Finke, whose startup Brimstone was awarded $189 million to build its first commercial-scale plant producing low-carbon cement using a proprietary chemical process. The company pieced together its early investment from smaller DOE sources and venture funders, Finke said, but the commercial facility was too expensive for its main backers. “Banks don’t have a financing product that takes that much risk, and VCs don’t have a product that’s the right size,” he said. The larger DOE grant makes it much easier to draw in a broader pool of investors, he said, and brings the company closer to making a product that can compete directly with traditional cement on cost. “There are lots of technological solutions to climate change, but few actually will give someone enough profit to make it happen,” he said. “That is really the gating thing.”

Notable

- Several of the largest grants in the program will go to companies headquartered in Europe, adding a new wrinkle to the climate tech tug-of-war between the U.S. and European Union.