The News

Many electric vehicles for sale in the U.S. are about to lose their tax credits, but that could counterintuitively fuel a race among automakers to lower prices, accelerating a process that Tesla initiated this year.

“The pricing wars have just begun,” said Alex Liegl, CEO of EV financing company Tenet.

Tim’s view

New U.S. Treasury guidelines tighten the criteria EVs need to meet to qualify for tax credits, prioritizing the long-term development of a domestic supply chain for battery materials and manufacturing capability over the near-term mass adoption of EVs. But the guidelines almost immediately reshape the experience and economics of buying an EV in the United States.

The guidelines require much of an EV’s battery components to be sourced from the U.S. or a designated list of trading partner countries, setting a bar that most automakers — still largely reliant on China for key minerals and parts — will struggle to meet. In the meantime, EV makers will likely lower their prices anyway while trying to increase their offerings of low-end models, analysts said, especially in the face of competition from internal combustion engine vehicles, prices for which are expected to fall this year by 5% for new vehicles and 10% for used ones. The average price of a new EV in the U.S. is $62,000, about $10,000 more than the average for all cars and trucks, but that gap is closing quickly.

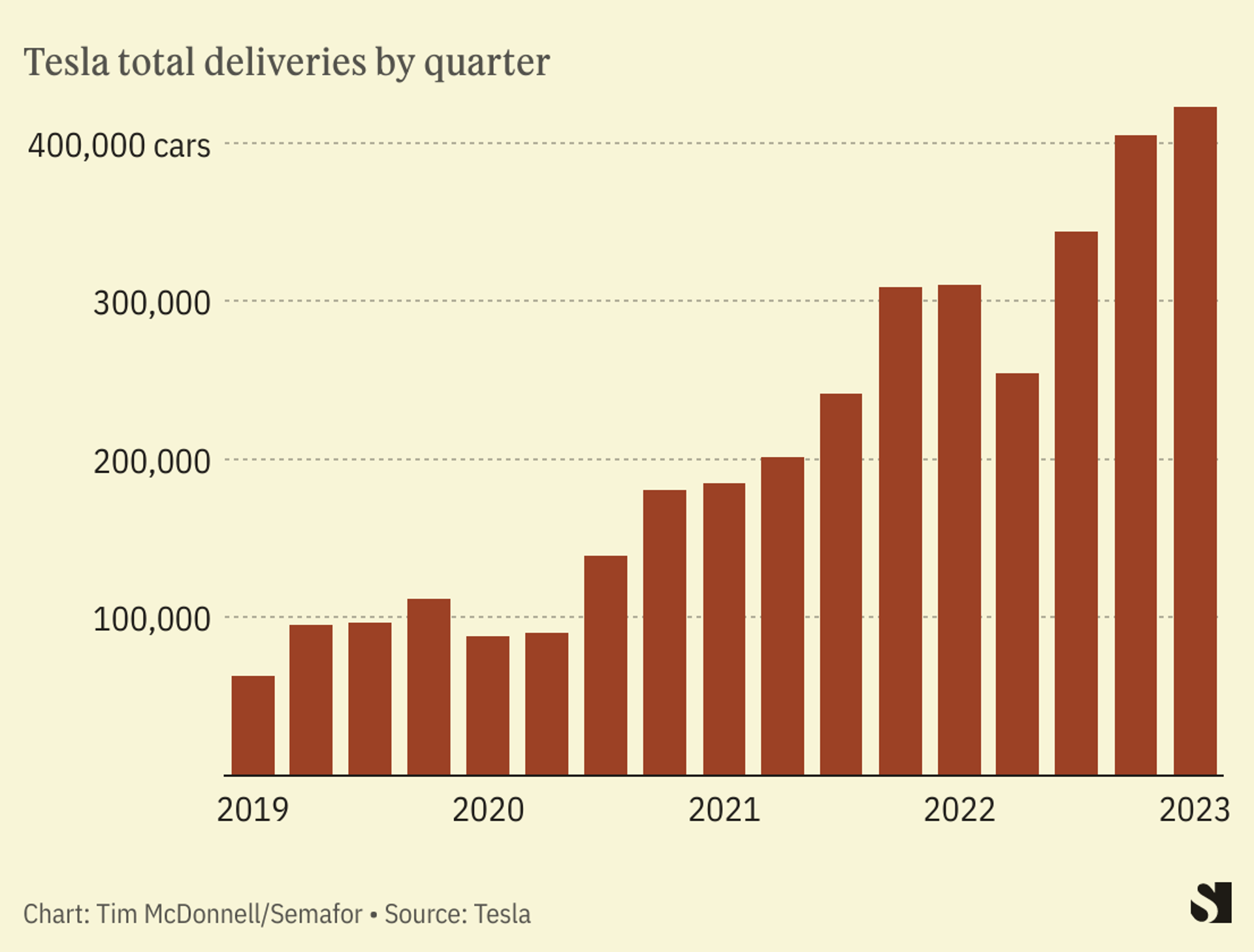

In January, Tesla slashed prices by up to 20% on some models in a bid to juice sales, especially as the EU and China rolled back some EV subsidies. The move seems to have paid off: On Monday, Tesla said it delivered 422,875 cars in the first quarter of 2023, slightly below analysts’ expectations but still a record.

Further price cuts are likely. Ford has already followed suit, as have several Asian carmakers. The cost of lithium, one of the most expensive battery materials, is falling as EV demand in China cools, and the Treasury is expected within the next few months to clarify a different set of tax credits for EV manufacturers (rather than consumers) that should speed up the process of building out domestic battery plants.

Tesla in particular has an incentive to keep prices as low as possible and “can’t afford demand destruction,” said Abhishek Murali, senior EV analyst at the intelligence firm Rystad Energy. The company announced plans last month to build a massive factory in Mexico, and needs to demonstrate to investors that it’s actually needed: “If Tesla isn’t able to clear existing inventory, they can’t make the case for scaling up,” Murali said.

Ford signaled a different tactic last week, suggesting it may even be willing to intentionally forego the tax credit in the interest of bringing down its overall production costs. The company will invest alongside a Chinese mining company in a $4.5 billion nickel plant in Indonesia, which will give it access to “some of the industry’s lowest-cost” nickel, an executive said. Beyond not moving the needle on the company’s U.S. supply chain, the investment also risks running afoul of fine print in the tax credit guidance that says cars will be disqualified if they contain any battery components whatsoever from “a foreign entity of concern.” The Treasury is expected to clarify later which countries or organizations meet that description, but it is broadly understood as a reference to China.

Any deals linked to China, therefore, are “a calculated political risk that some firms might want to take,” said John Miller, ESG research director at TD Cowen, an investment bank.

Quotable

“It will be very challenging for automakers to meet the new mineral and manufacturing requirements until the battery supply chain in the U.S. becomes much more robust,” Grant Ray, VP of global market strategy at U.S. battery producer Group14, said in an email.

Room for Disagreement

Price cuts are “a cat-and-mouse game,” Murali said, because once you start, consumers expect them and may delay purchases, which only reinforces their need. The market was unimpressed with Tesla’s record quarterly deliveries, with the company’s share price down by almost half compared to a year ago.

Tesla and other automakers are now essentially engaged in a game of chicken, to see who can stomach lower profit margins for the longest while the U.S. supply chain catches up with the Treasury’s demands. Tesla’s advantage is that its margins are already the highest in the industry, but the likes of Ford and GM have much deeper pockets overall and can plow cash from their traditional businesses into EVs. Other EV startups like Lucid and Rivian — both of which announced layoffs in recent weeks — are in a more precarious position.

The View From China

The price wars have been especially fierce in China, the world’s biggest EV market, where nearly every domestic and foreign automaker has cut EV prices steeply this year. Tesla’s biggest competitor there is BYD, which has a very well-integrated local supply chain and should be able to keep production prices low. Already, despite the price reductions, Tesla’s market share in China fell from 15% in 2020 to 10% in 2022.

The View From Washington State

Ripple effects from the tax credits are already visible in the U.S. This week Group14 broke ground on what is expected to be the world’s largest factory for silicon battery materials, in Moses Lake, Washington.

Notable

Despite the momentum in scaling up EVs, the transition away from traditional engines is largely ignored on automaker’s balance sheets. The accelerated depreciation of old manufacturing hardware and other financial risks of the energy transition are not included on most automaker’s financial statements, analysis this week by the think tank Carbon Tracker found.