The Facts

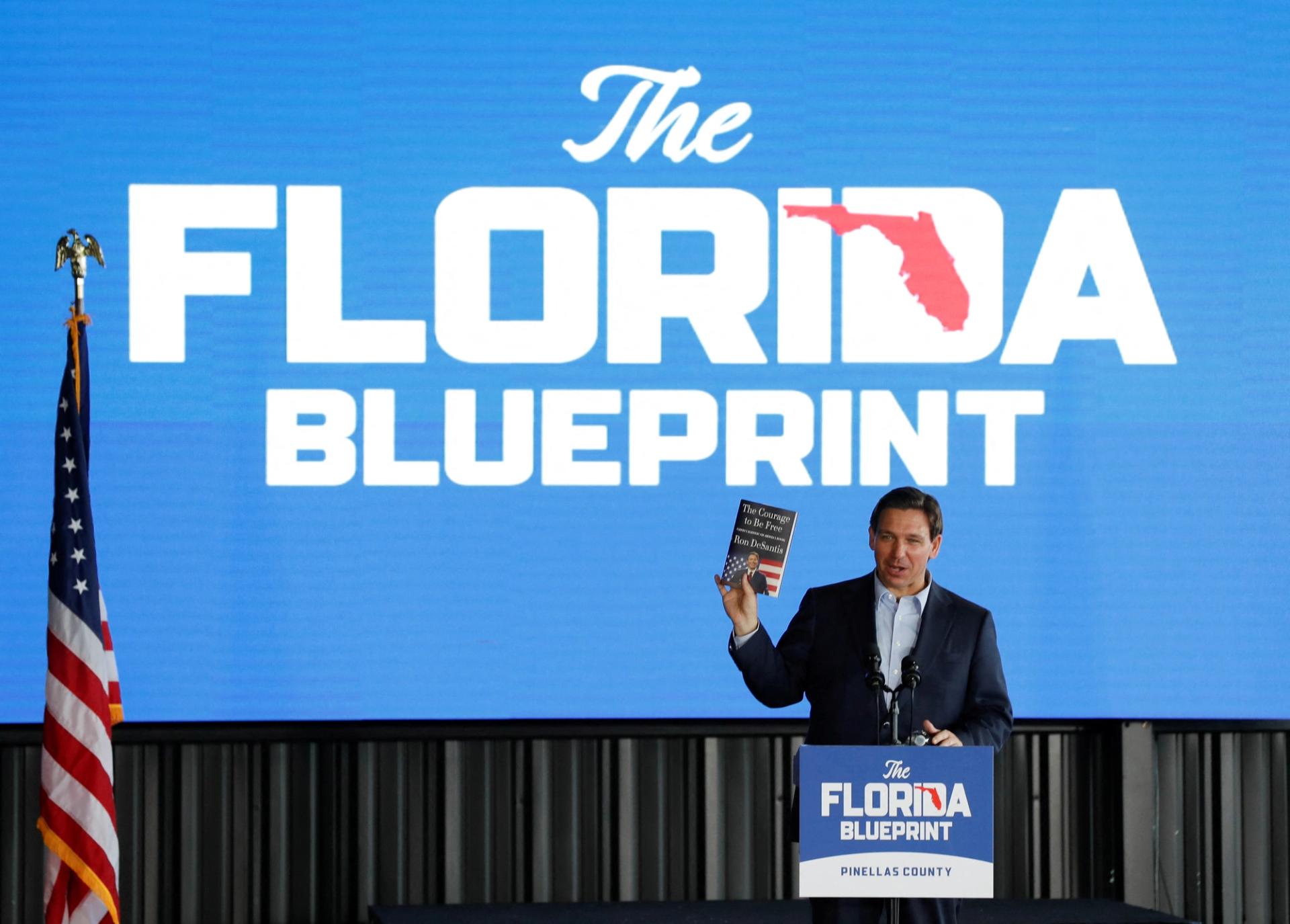

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis won his current office on a slew of pro-environment policies, particularly a promise to confront the red algae blooms that slammed Florida’s tourism and fishery economies that year. He has maintained a sterling reputation on environmental conservation, a universally popular agenda in the home of the Everglades, and initiated a program that has doled out $1 billion since 2021 in grants to help communities and businesses recover from and prepare for flooding.

Meanwhile, starting from his earlier career in Congress up to now, he’s questioned climate change science, voted to expand fossil fuel consumption and limit renewable energy, and championed measures to punish financial firms that account for environmental issues in their investment decisions.

It’s a contradictory record on climate and environmental issues driven by the unique and sometimes conflicting priorities of the state’s voters and deep-pocketed campaign contributors, and one Donald Trump’s main challenger for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination may struggle to balance on the campaign trail.

“If you’re putting in infrastructure to deal with chronic flooding but not focusing on the root of the problem, it’s a waste of a lot of taxpayer dollars,” said Yoca Arditi-Rocha, executive director of the CLEO Institute, a Florida environmental advocacy group. “We’re mopping the flooded bathroom over and over but not turning down the water.”

A spokesperson for Wesley Brooks, who leads the state’s resilience office, did not return a request for comment.

Tim’s view

DeSantis has fine-tuned his environmental message to serve him well in Florida politics. But to succeed on a national stage, it may need to be recalibrated, as clean energy emerges as a major driver of job creation and anti-ESG policies fall out of favor among conservative lawmakers and their backers in the financial sector.

Some of his top gubernatorial campaign contributors were prominent Florida conservationists, including Bruce Rauner, former governor of Illinois and a trustee of the state’s Nature Conservancy branch, and Paul Jones, a hedge fund billionaire who founded the Everglades Foundation, a conservation group. The Resilient Florida Program, passed by the state legislature with broad bipartisan support and signed by DeSantis, has been widely lauded by environmental groups as it pays for sea walls, drainage canals, and other climate adaptation infrastructure.

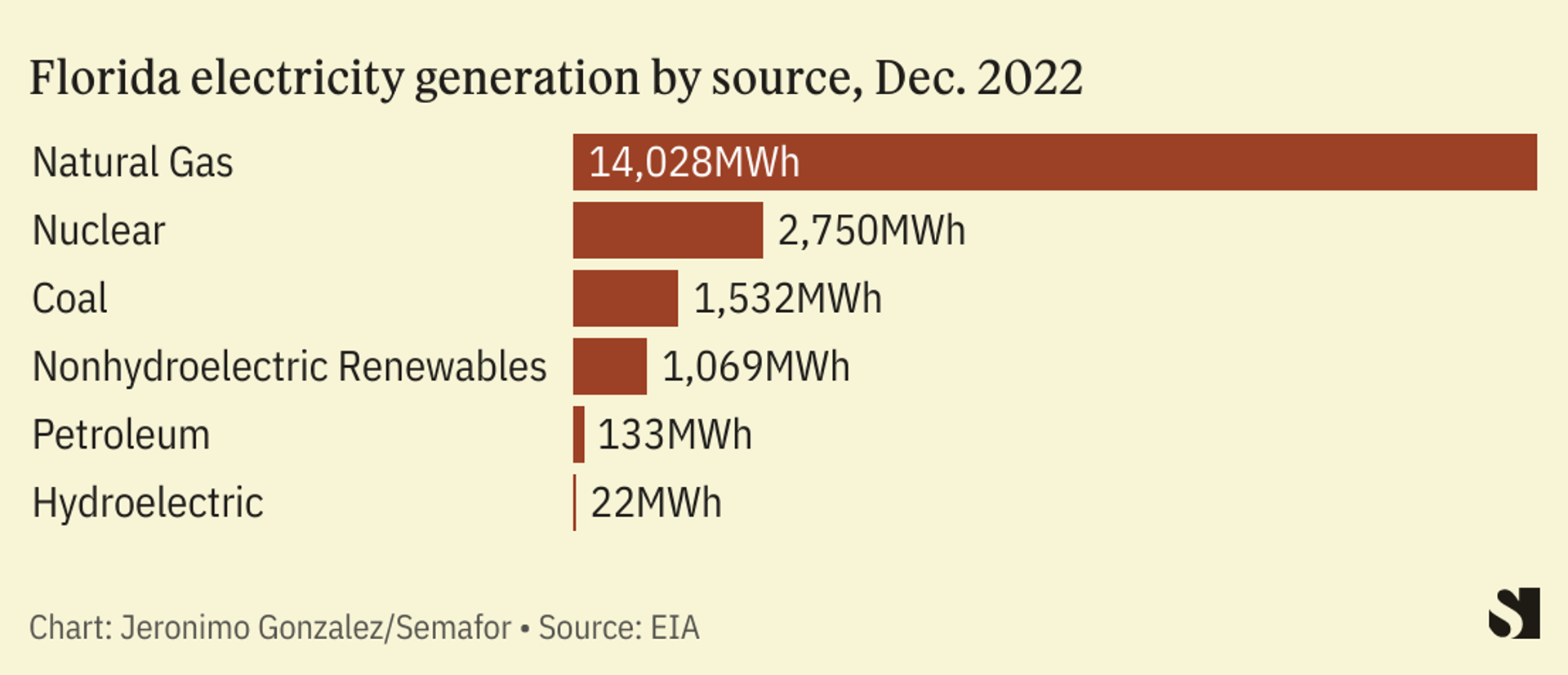

But electric utilities are also a powerful political force in the state, and spent nearly $10 million during the 2019 election cycle, mostly on DeSantis and other Republican candidates. Florida Power & Light, the largest, relies mostly on natural gas and has campaigned heavily against policies to speed the deployment of rooftop solar. All five members of the state’s Public Service Commission, which regulates utilities, were appointed by DeSantis, and observers say they’ve made it easier for utilities to hike their rates without investing sufficiently in low-carbon energy. Other top contributors to DeSantis’s gubernatorial campaign include the owners of Florida-based oilfield services and oil refining companies.

“We’re seeing utilities lobby on tax breaks for [natural-gas-derived] hydrogen, natural gas, and other things that translate to further investment in fossil fuel infrastructure,” said Alissa Schafer, a Florida-based researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, a utilities watchdog group. “The Public Service Commission are rubber-stampers, and DeSantis is letting them do that.”

DeSantis also signed a 2021 law that prohibits local governments from regulating the sources of energy used by utilities, which effectively prevents them from adopting climate ambitions that go beyond the governor’s, as some places like Tampa have tried to do.

While a member of Congress, from 2013-2018, DeSantis voted against renewable energy tax breaks and carbon taxes, and in favor of offshore drilling and other policies favorable to fossil fuels. His voting score from the League of Conservation Voters, which tracks environment-related Congressional votes, is 2%, low even among Republican representatives. That includes votes DeSantis took against the kinds of conservation issues he later supported as governor, such as opposing budget increases for national parks and voting to weaken the Endangered Species Act during droughts.

But DeSantis was willing to break with utilities when he vetoed a 2022 bill to end the practice of “net metering,” a grid management practice that makes rooftop solar cheaper for homeowners. That veto showed that DeSantis may be willing to change course and support pro-climate measures when they’re widely popular with voters.

Quotable

“When people start talking about things like global warming, they typically use that as a pretext to do a bunch of left-wing things that they would want to do anyways. And so we’re not doing any left-wing stuff.” — DeSantis in a 2021 press conference.

Room for Disagreement

DeSantis’s anti-ESG push is becoming unpopular even among some ostensible allies.

Last year, he passed a rule to block state pensions from accounting for ESG considerations in their investment decisions. He’s backing state legislation to impose similar restrictions on all public funds.

In a legislative hearing this month, a lobbyist for the Florida Bankers Association spoke out against the proposal, saying it would dramatically increase compliance costs, especially for small community banks. That sentiment has been spreading in other states that have considered similar bills, even in strongly Republican-controlled legislatures, as more details come to light about how much it will cost taxpayers to both narrow the pool of asset managers they can do business with and ignore the financial risks of climate change. Anti-ESG activism, in other words, is unlikely to be a winning strategy in a presidential election.

The View From Georgia

DeSantis has also been a vocal opponent of the Inflation Reduction Act, a massive bill pushing climate tech, which he called “the middle finger to the American public.”

That’s a marked difference from the position taken by neighboring Republican governor Brian Kemp of Georgia, who has successfully seized on IRA funding to pitch his state as a major destination for factories producing batteries and other clean tech. “Why hasn’t [DeSantis] been taking that opportunity to create more jobs in Florida?” Arditi-Rocha said. “It’s definitely mind-boggling.”

Notable

- Desantis has touted Florida’s lack of an income tax, among other tax breaks, as a draw for investment and relocation. But the climate crisis is driving the state’s insurance rates into the stratosphere. Property rates are poised to jump 60% this year, and more than a dozen insurers have left the state.