The News

A record — and growing — climate tech war chest risks fizzling out as the sector’s startups struggle to pay off their early investors.

Climate-focused investment funds grew faster than they have in years during the first quarter of 2024, bucking the trend of slow fundraising that has descended on the overall venture capital market. But that momentum could run out, fund managers say, if more climate tech startups can’t “exit” to an initial public offering or high-dollar acquisition.

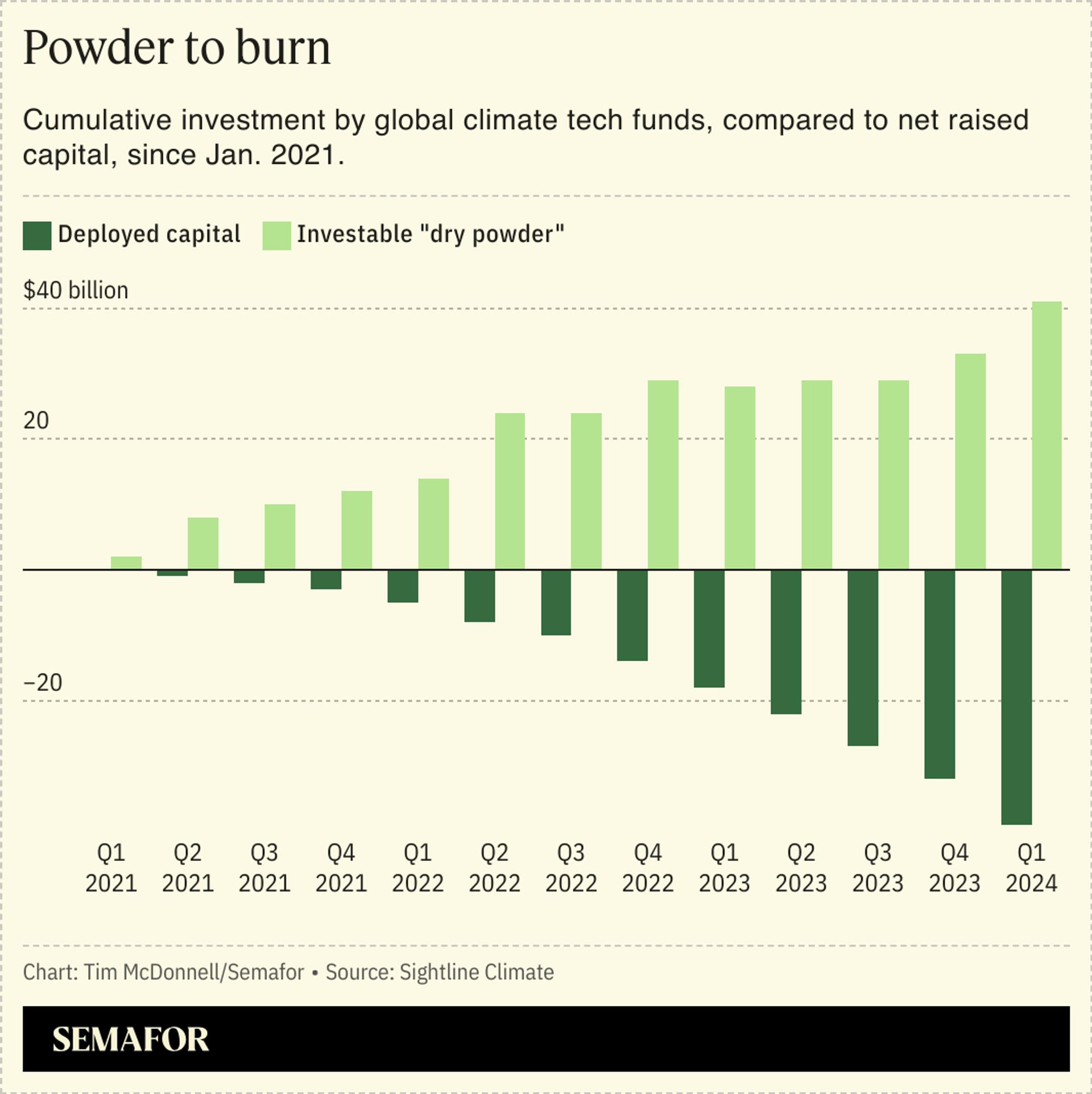

Since January, climate funds — including venture capital, private equity, and infrastructure funds — have raised at least $28.2 billion, mostly in eight “megafunds,” such as Brookfield’s $10 billion Global Transition Fund. Add up fundraising since 2021 and deduct what has already been invested — and money is indeed flowing out the door — and you’re left with a global climate tech war chest of about $41 billion, according to the analytics firm Sightline Climate.

In this article:

Tim’s view

Given that venture capital overall just had its worst quarter for fundraising since 2016, the climate tech figures suggest a growing coalition of investors riding the wave of the Inflation Reduction Act and other policy enticements, willing to place long-term bets on both brand-new startups and more advanced companies looking to build commercial-scale climate tech factories and clean energy farms. But that wave is probably peaking. Unless more climate tech companies can prove their worth to their initial investors, the sector’s financial gears could grind to a halt.

“We hear from a lot of fund managers, first-timers as well as institutional and PE managers, that it’s harder than ever right now to fundraise,” Sightline CEO and co-founder Kim Zou said.

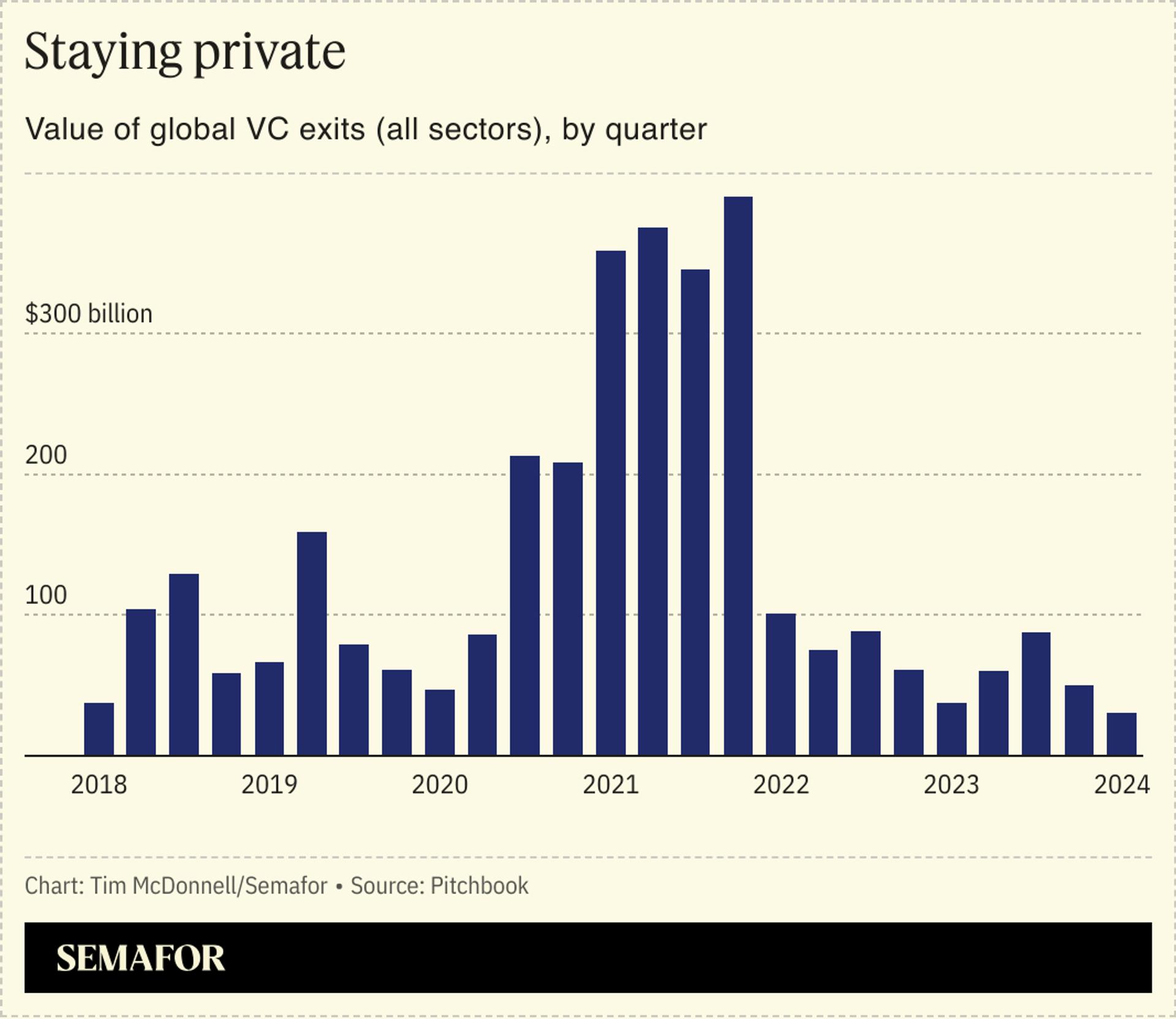

Stubbornly high interest rates are one obstacle. But a deeper challenge is that few climate tech companies are going public or being sold, the types of “exits” that normally return money to the startup’s original investors, who often recycle it back into other startups.

“In 2024, all eyes are on the IPOs,” said Ari Newman, co-founder of the Colorado venture firm Massive. “There’s so much liquidity locked up in privately held companies right now, that unless that frees up, if we don’t break the logjam, where is the money going to come from?”

IPOs have slowed in general, and for climate tech startups in particular. The dismal performance of many climate tech companies that went public via SPAC around 2021 has made others and their investors want to gather more proof of profitability before going public. And the fact that 80% of climate tech acquisitions go undisclosed, according to Sightline, is an indication that the terms for those who sell out to a larger company or PE firm are usually nothing to brag about.

None of this is too surprising. Climate tech is attempting to execute sweeping, expensive changes to the global economy, and for the most part is just too young to have many candidates for a flashy exit. The overall increase in climate tech “dry powder” conceals key funding gaps, especially for middle-stage companies working on their first large-scale projects, which make it harder to reach that level of maturity.

There have been a few prominent examples of successful climate tech exits in the last year. The share price of Nextracker has doubled since the solar panel hardware company’s $638 million IPO in Feb. 2023. Carbon capture company Carbon Engineering got snapped up by Occidental Petroleum for $1.1 billion in August, illustrating how climate tech might court deep-pocketed, high-carbon corporate buyers.

The trouble is, investors need more exits not only to get their money back into circulation but also to collect tangible evidence of what works. Without more of them, many potential investors are sitting out, said Ben Wolkon, a partner at the New York venture firm MUUS Climate Partners: “In our view there are many billions of dollars on the sideline that are potentially interested in climate tech but are taking a very cautious approach.”

The View From Sweden

One of the most likely contenders for an IPO in the near term is Sweden’s NorthVolt. The company, Europe’s largest domestic battery maker, raised $3.4 billion in debt in January to build and expand gigafactories in Europe and Canada and could be valued at $20 billion in an IPO, analysts say. Another is H2 Green Steel, which is building the world’s largest facility to make steel using green hydrogen, also in Sweden. In the U.S., industrial decarbonization companies with strong recent fundraising and scale-up projects in the works like Electric Hydrogen and Boston Metal are others to watch, Zou said.

“They have to get through building out those first commercial projects,” she said. “If those are successful, I think the IPO window opens for them.”

Room for Disagreement

If climate tech investors are becoming choosier about who they allow to manage their money, it’s because there’s been a “flight to quality” to fund managers with more climate-specific experience, said Alexandra Harbour, founder of the Venture Climate Alliance, a coalition of VC firms. That’s not a bad thing — it’s a sign funders are becoming more realistic about what it takes to build a successful climate startup. And the growth of climate “megafunds” shows there’s growing participation from sovereign wealth and pension funds that can afford to be very patient.

“For certain folks that are investing along the lines of traditional venture in software, I’m sure the lack of exits in climate tech is preventing them from doing more,” Harbour said. “But there’s a robust ecosystem of investors who understand the space and see the writing on the wall. I don’t think those folks are going away anytime soon.”