The News

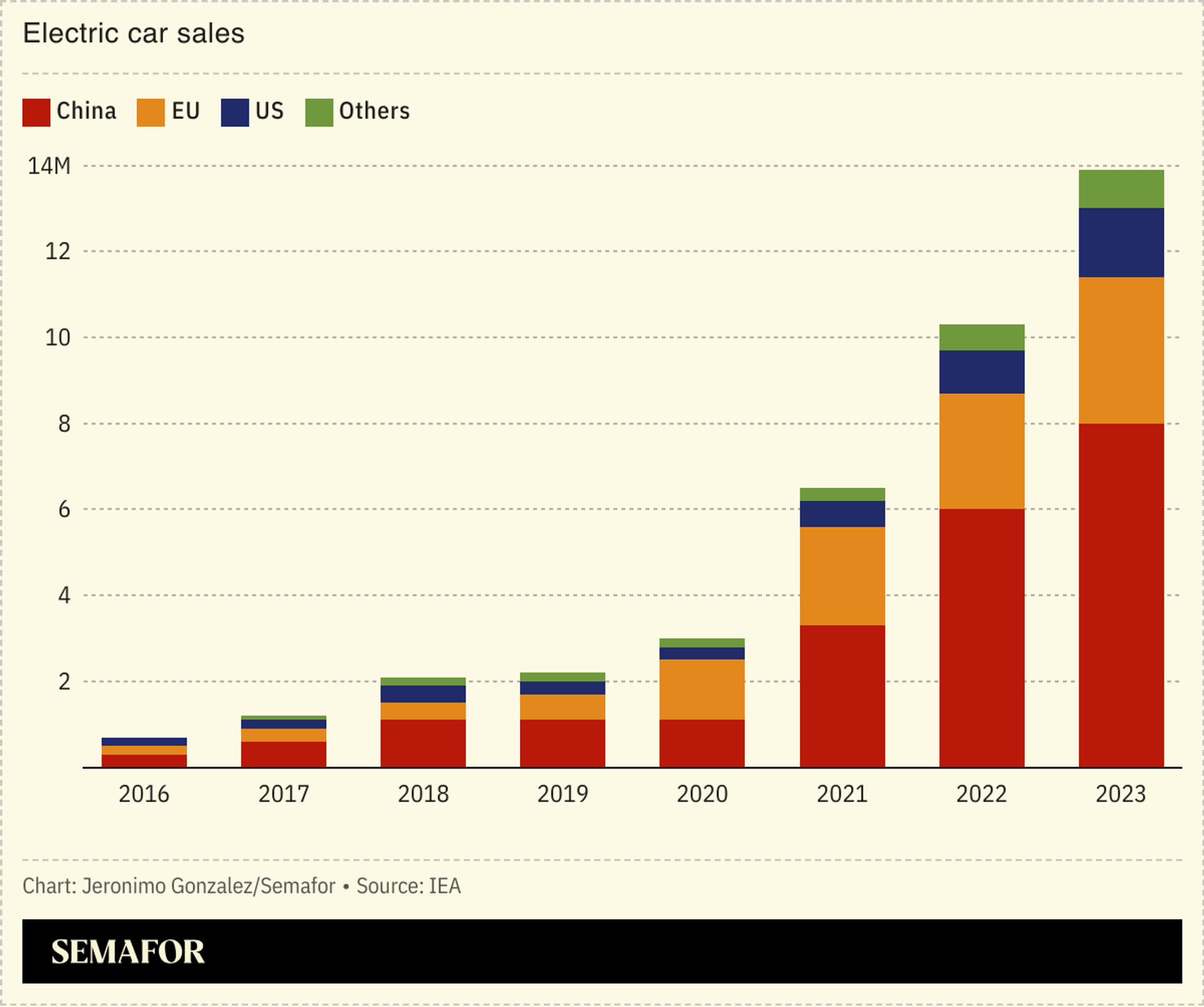

China is the most important country in the world when it comes to the future of electric vehicles: It accounts for about 60% of all global EV sales, its market for EVs is surging, and it is home to the planet’s biggest EV manufacturer.

So a recent survey showing that more than a fifth of battery EV owners in China want their next car to be powered by fossil fuels is understandably raising alarm bells in the industry. Growth in sales of EVs has long been plagued by range anxiety. Enter a new challenge — what EVCIPA, a charging-facility trade body, calls “energy-replenishing anxiety.” In effect, users are concerned about limits to charging infrastructure.

It spotlights one of the major challenges to the energy transition, and raises questions of how Chinese authorities respond. The country is such an EV behemoth that the speed bumps it hits — and the solutions it uses — can serve as valuable lessons for the rest of the world.

Know More

China’s “new energy vehicles” — which include battery, plug-in hybrids and fuel-cell vehicles — grew their market share sevenfold between 2019 and 2023, and analysts project the industry will continue expanding by around 10% each year for the next five.

Alongside that remarkable growth, however, has been frustration: The survey from McKinsey China pegged battery EV buyers’ “regret rate” as surging from 3% in 2022 to 22% last year, which its report blamed largely on limited charging infrastructure. Chinese consumers’ “acceptance rate” of new energy vehicles in general also dropped from 68% in 2022 to 62% in 2023, meaning fewer people were looking to buy these vehicles.

Experts I spoke to raised questions over the research’s conclusions, and over the survey’s selection sample. (McKinsey declined to respond to my questions about its survey.) The McKinsey survey is not an outlier, though: Travel range, charging time, and lack of charging stations available are “firmly” the top three concerns for potential EV buyers in China, according to S&P Global Mobility, an international market intelligence provider.

Evolving expectations could be partly to blame, Phate Zhang, the founder of the Shanghai-based industry outlet CnEVPost, told me. Early adopters of EVs were often more affluent, curious, and well-researched on the topic. But as the market has ballooned, consumers quickly shifted from trailblazers to more everyday users, who may be less prepared for challenges associated with EVs, he said.

Xiaoying’s view

China’s problem is not that its people do not want to buy EVs. Quite the opposite: The real challenge the country faces is to expand its charging network fast enough to match its astonishing EV growth rate.

It is a problem that countries the world over will face, sooner or later: As EV sales gather pace, whether through government incentives, such as the U.S.′ EV tax credit, or through diktats — the U.K. will ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars in about a decade — the capability to charge them quickly needs to expand. That means huge expansion of electricity grids, transmission infrastructure, and charging points, the last of which can be a particular challenge in urban areas where the vast majority of people do not have driveways and live in tower blocks.

China — thanks to the sheer size of its market, and its huge progress in deploying EVs — offers a case study on all counts.

The country already has the world’s largest EV charging network, having installed more than 8.5 million pillars nationwide. On average, every 2.5 new energy vehicles share one charging pillar in China. In comparison, the ratio in the United States — the world’s third largest EV market — was around 15:1 by the end of 2022.

“China’s speed of building EV charging infrastructure has already been very fast,” Zhang told me. ”[It] is installing charging units at a speed that considers its actual EV stock.”

But they are heavily concentrated: More than 70% of China’s public charging posts are in fewer than a third of the country’s provincial-level regions, such as affluent Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiangsu, according to EVCIPA. Charging also takes too long because only 20% of the charging pillars along motorways are fast-charging units, ultimately resulting in long lines of cars waiting at service stations, according to China Auto News.

Beijing is aware of the problem and has taken action. In June, it instructed all regional governments to improve the distribution of charging facilities, build more pillars in residential compounds, and bring more services to rural areas. It also called for more innovations on fast charging, wireless charging, battery swapping, and other such technologies.

Progress, even if limited, is already evident. EV owners in Jiangsu can now find out where to charge their cars cheaply without queues with an app developed by the local branch of the State Grid. EV makers are improving battery charging speeds, too: The latest addition to the Chinese EV market, Xiaomi’s SU7, can achieve a range of 135 miles (220 kilometers) in just five minutes of charging, and 315 miles (510 kilometers) in 15 minutes, using technology from battery giant CATL. The model starts at RMB 215,900 ($29,870), underpricing its Tesla equivalent, the Model 3. NIO, another EV maker, is betting on battery-swapping, particularly for urban residents without access to driveway charging facilities, building more than 2,300 sites nationwide where drivers of its cars can hand over their vehicle’s battery for a fully-charged one in just a few minutes.

Still, China has a ways to go. It may have 8.5 million charging points now, but Lu Wenliang, an EV researcher, told the China Economic Times the country needs 30 million by the end of next year to meet a government target of having one pillar for every two “new energy vehicles.”

Room for Disagreement

Despite the high “regret rate” found by McKinsey China, the country’s consumers and manufacturers are making the conversion to EV at a fast rate. China EV100, a Beijing-based think tank, predicted annual sales of new energy vehicles in the country will soon smash the 10-million mark for the first time.

At the same time, a huge number of successful Chinese EV makers are expanding overseas, including BYD, the world’s biggest manufacturer of electric vehicles. Even homegrown limousine brand Hongqi — a model of which proudly shown off by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to U.S. President Joe Biden during their summit in California last year — is working on an electric model, using BYD’s blade batteries, which can be charged from 10% to 80% in 25 minutes.

The View From the US

EV sales in the U.S. increased from about 125,000 in the first quarter of 2021 to 375,000 in the third quarter of 2023, and are projected to rise by 32% this year. But the percentage of shoppers “very likely” to consider buying or leasing an EV for their next vehicle has actually declined for five months in a row, slipping to 22.5% in March, according to Stewart Stropp, executive director of EV Intelligence at J.D. Power, an analytics firm headquartered in Michigan.

Charging issues are, again, the sticking point. “Lack of charging station availability is consistently the number one reason cited each month [by EV rejecters], with other charging-related reasons occupying the other top spots, along with purchase price,” Stropp told me.

The Biden administration is trying to tackle the headache by investing $5 billion in building a national EV charging “backbone,” which will see high-speed ports installed along major roads and freeways. Tesla is also opening a portion of its 200,000-strong Supercharger network in the United States to rival brands, also as part of the White House’s effort to fast-track the buildout of charging infrastructure.

Notable

- As range anxiety remains high on the list of concerns, plug-in hybrid vehicles have been making inroads in China. An Limin and Ding Yi explained how Chinese automakers are responding to the market with more hybrid models in Caixin.