The News

NAIROBI — Kenya’s budget crisis has left its government with a hard choice — delay paying public workers and face widespread unrest, or risk defaulting on its debt.

President Willliam Ruto’s administration has, so far, opted to delay salary payments to thousands of civil servants by as much as three months, prompting strike threats. It comes just weeks after thousands of Kenyans staged demonstrations against the rising cost of living.

The president’s chief economic adviser, David Ndii, said late salary payments were due to liquidity problems caused by the rising cost servicing debts. He summed up the government’s predicament in a tweet: “It’s reported every other day debt service is consuming 60%+ of revenue. Liquidity crunches come with territory. When maturities bunch up, or revenue falls short, or markets shift, something has to give. Salaries or default? Take your pick,” he wrote on April 8.

The cost of servicing Kenya’s debt, as a proportion of ordinary revenue, has risen from 49% in 2019/20 to 65% in 2022/23.

Speaking on the Citizen TV news channel on Monday, Ndii said defaulting on debts was not an option. “We are not insolvent. We can finance repayments. It is a significant sacrifice but we are actually able to pay,” he said.

The Central Organization of Trade Unions (COTU) on Tuesday said members of two trade unions representing civil servants intend to go on strike. The Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union has also threatened to carry out industrial action. More than 80,000 public sector workers could go on strike if all three unions carry out their threat.

Know More

Timothy Sudi, a nurse in Kenya’s central Kiambu County, told Semafor Africa that he and his colleagues were growing accustomed to problems with their salaries. “We’re used to figuring out alternatives to pay bills and pay debts,” he said. However, one of those alternatives — savings clubs used by many to manage their finances — are likely to feel the knock on effect of payment disruption.

Savings and Credit Cooperative Organizations, commonly known as Saccos, offer lower interest rates on loans than traditional banks but rely on members making payment to their savings accounts. “Paying back loans on time and making regular deposits… makes it easy to get a loan whenever I’m pressed for quick finances,” said Miriam, a teacher in eastern Embu County, who said late Sacco deposits after her wages were disrupted could harm the safety net provided by her Sacco.

Vivianne’s view

President Ruto came to power after last year’s election in which he campaigned as the “hustler” candidate who cared about the country’s poorest people. He inherited problems from his predecessor, Uhuru Kenyatta, but is deepening those issues by making the government bigger – and the wage bill along with it.

Last month he increased the number of senior government officials known as Cabinet Administrative Secretaries to 50, up from 29 under Kenyatta. This increase will cost taxpayers up to 13.2 billion shillings ($98.2 million) over five years, according to the country’s Public Service Commission.

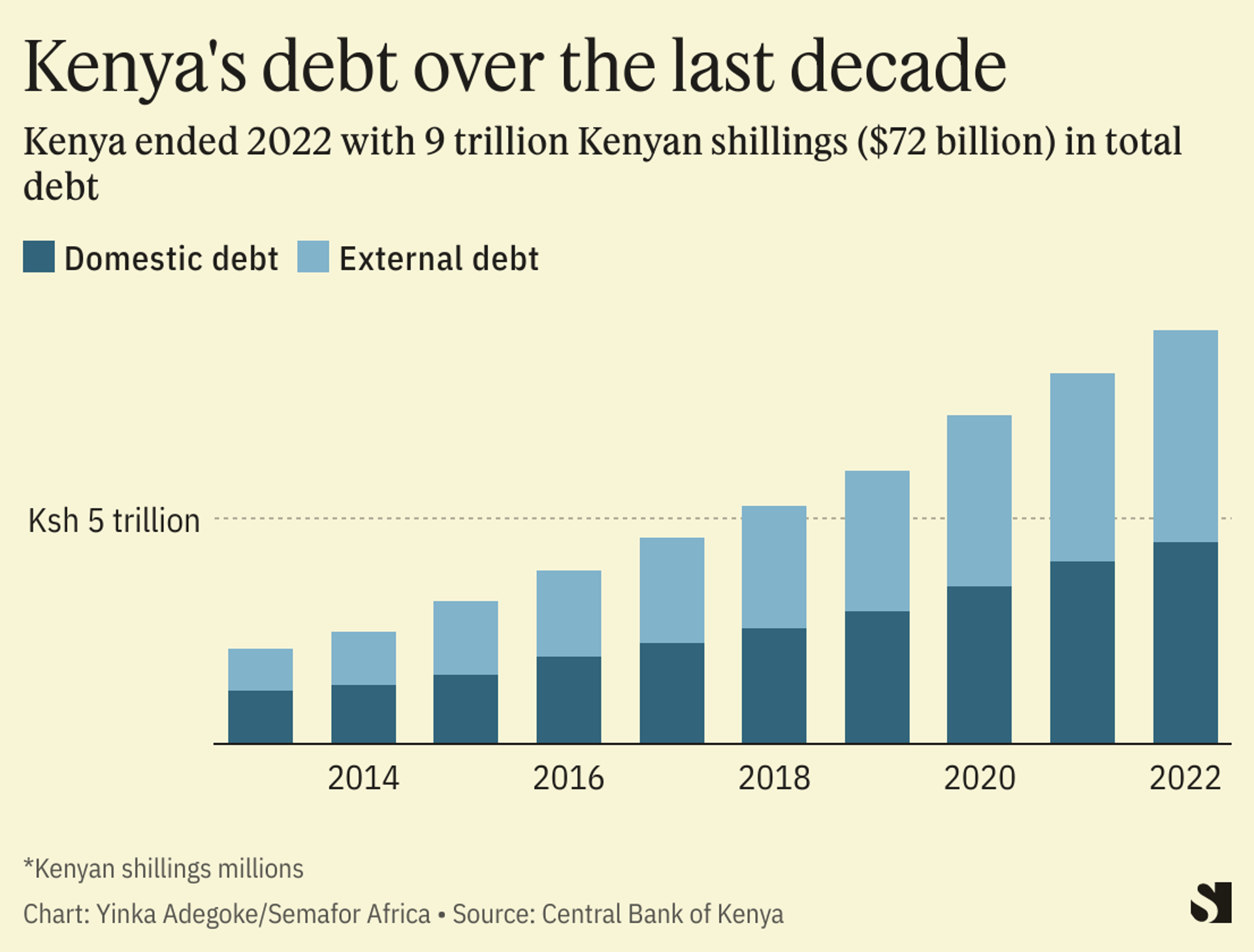

Ruto’s administration needs to be more prudent because the debt problem is getting worse. Kenya’s public debt crossed 9 trillion shilling ($72 billion) in December, pushing the country nearer to the 10 trillion shilling ($80 billion) debt ceiling set by parliament last June. As the shilling continues to weaken, the cost of servicing foreign debts will rise.

The country’s stability is at stake. People are angry about the cost of living, as we saw last month when thousands of people took to the streets in big cities for demonstrations on this issue. A failure to get government finances under control could lead to a repeat of that unrest, particularly if many aren’t being paid on time, or not at all.

Room for Disagreement

“The cash crisis is putting a strain on businesses and the entire economy but it is a situation that can be salvaged,” said Ken Gichinga, chief economist at analytics firm Mentoria Economics in Nairobi. “Embarking on austerity measures and budget cuts is the wrong way to go about this, and it will drive the economy into a recession,” he added.

Gichinga said the government should focus on increasing revenue collection through progressive tax policies. The current revenue collection is about 15% of the country’s GDP, he said, which is “significantly lower” than a country such as Denmark, which collects about 35% of its GDP.

The View From South Africa

Shani Smit-Lengton, an economist at advisory firm Oxford Economics Africa said Kenya’s situation was down to poor debt management exacerbated by a regional drought, the impact of the global pandemic, and the fallout from war in Ukraine. She said the World Bank and IMFare expected to disburse funding this quarter to offer some reprieve, but “we still expect existing challenges to persist.”

“The government needs to increase dollar inflows and improve its fiscal position. This can be done through promoting tourism and broadcasting attractive investment opportunities,” she said.

Notable

- Several African countries are, like Kenya, grappling with a shortage of dollars needed to pay for foreign debts, essential goods and industrial inputs. Others include Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia and Egypt. Development economist Christopher Adam, in The Conversation, explains the causes of these shortages and how they can be remedied.

— with Alexis Akwagyiram