The News

Top global banks are divided over how to measure the carbon footprint of their finances, and many are falling short of the Paris Agreement climate goals.

In interviews this week with Semafor, officials at JPMorgan Chase and Citi — two of the U.S.‘s biggest banks, which hold opposing views on how to set decarbonization targets for their fossil fuel lending — said they are focused on financing to oil and gas companies’ nascent low-carbon divisions.

Two new reports indicate, however, that regardless of their approach to target-setting, these and other banks aren’t attaching sufficient strings to the tens of billions of dollars they are plowing into fossil fuels each year to push their clients quickly enough toward net zero. And because banks sit at the fulcrum of the global economy, the stakes for them to set ambitious climate targets, and meet them, are high.

Tim’s view

Banks are understandably torn between the imperatives of cutting emissions and supplying fossil fuels to an economy still hungry for them. There is no easy choice here. But in setting climate policies that attempt to satisfy both, many lenders, especially in the U.S., end up compromising on reducing emissions, especially in the near-term. To some extent, a bigger problem is that lenders are just beginning the process of discussing decarbonization with their oil and gas clients. Val Smith, chief sustainability officer of Citi, said the bank is for now working on “assessing where [high-carbon clients] are in their own decarbonization journey today.”

There are two types of emissions targets for banks: Absolute, which aims for a specific total volume of emission cuts relative to a baseline, and intensity, which aims for a specific level of emissions per dollar of financing.

Documents leaked last week from the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, an industry group that includes all of the world’s biggest banks, show that some lenders opposed a proposed requirement to set absolute emissions targets for energy sector financing. Most European banks have adopted such targets. Among U.S. banks, only Citi and Wells Fargo have, while JPMorgan, Bank of America, and others have intensity targets.

Banks with intensity targets argue their system allows more flexibility to finance oil and gas companies with large carbon footprints that are gradually shifting their business model. But proponents of an absolute-only approach — including a committee of U.N. experts who weighed in on the question last year — argue that intensity targets allow total emissions to rise. While financing fossil fuel companies’ decarbonization efforts is a laudable goal, proponents say, in practice banks are too lenient in these transactions to drive rapid change. Most, for example, have no restriction against lending to oil and gas companies pursuing new drilling projects, a practice the International Energy Agency says is incompatible with the Paris Agreement.

“It’s difficult to see the rationale for an oil and gas intensity target,” said Anderson Lee, a private-sector finance researcher at the World Resources Institute, a think tank. “You can have an absolute emissions target and still help oil and gas companies get the resources they need to move away from fossil fuels.”

Quotable

“We believe our approach to climate, including the use of intensity targets, appropriately takes into account global realities and sensibly balances the aim of emissions reduction and energy security by incentivizing reductions over time consistent with the availability of alternatives to fossil fuels.” — Charlotte Powell, spokesperson for JPMorgan Chase

Know More

In an analysis this week of the climate plans of six major U.S. banks, Ceres, a sustainable-finance research and advocacy group, concluded that none — whether they use intensity or absolute emissions targets — are on track to be where they need to be by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5 C. Only Bank of America is on track for 2 C. (A Citi spokesperson disputed the Ceres report’s methodology and said the bank is Paris-aligned; spokespeople for Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan declined to comment.)

“According to their plans, they’re all heading in the right direction in terms of lowering their carbon footprint,” said Steven Rothstein, managing director of a capital markets program at Ceres and an author of the report. “But none of them are getting there fast enough.”

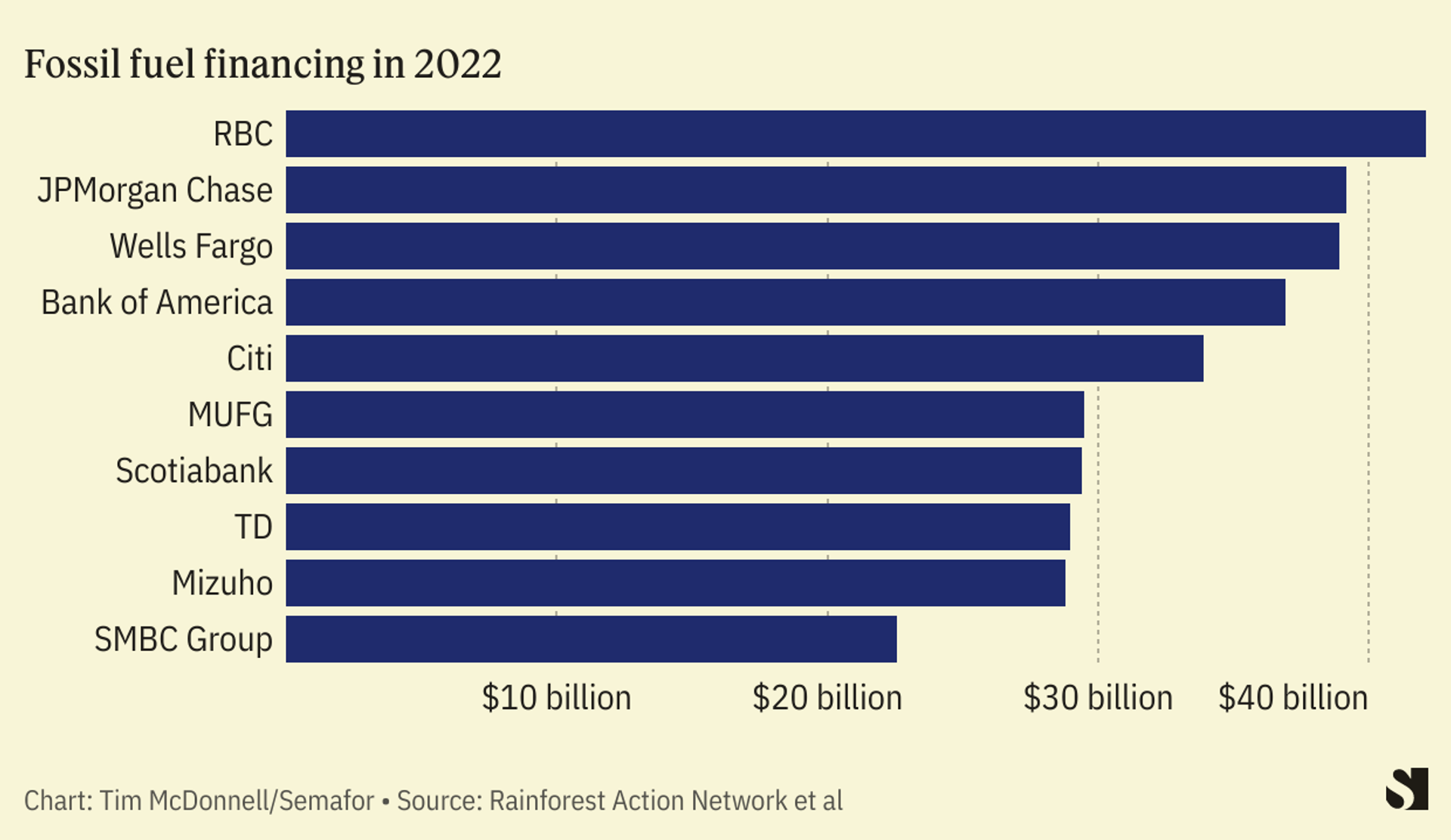

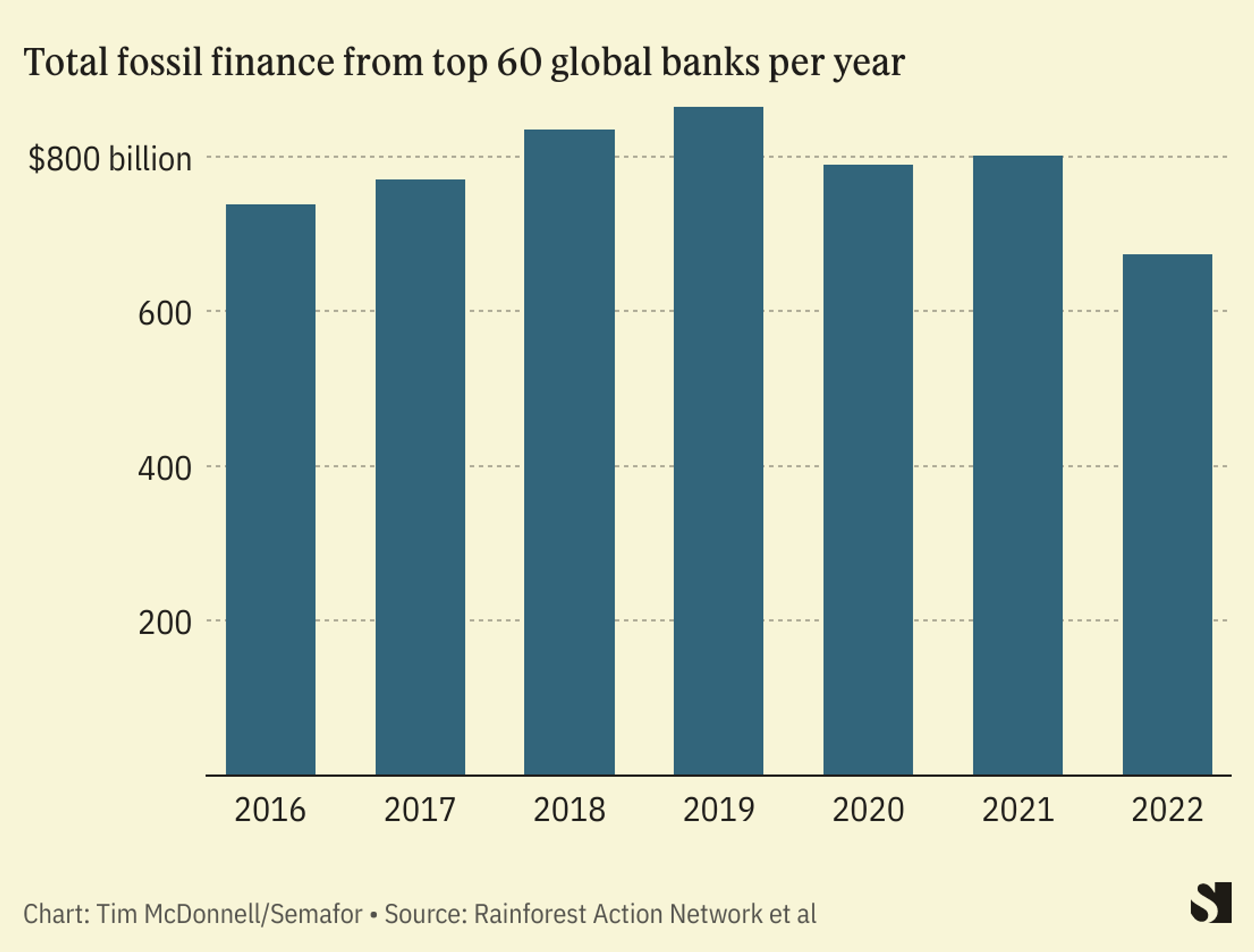

Meanwhile, a coalition of environmental groups led by Rainforest Action Network published their latest annual tally of fossil fuel financing by the 60 largest global banks, which concludes they have dedicated $5.5 trillion in total to oil, gas, and coal since 2016. That figure is a proxy measure of banks’ exposure to energy transition risk, to the extent that oil and gas companies that are clinging to their traditional business model face losses from the falling price of oil and the early retirement of pipelines, power plants, and other infrastructure.

Transition risk is a main reason shareholders at JPMorgan, for example, have filed resolutions this year calling on the bank to disclose more details of its transition plan and set absolute emissions targets for 2030, measures the bank opposes. And the way oil and gas companies reacted to record-breaking profits in 2022 — ramping up shareholder payouts and making only tiny increases to their already-tiny low-carbon spending — should be a red flag to banks, said April Merleaux, an author of the RAN report.

Room for Disagreement

Intensity targets may be a good fit for sectors other than oil and gas. The electricity sector, for example, needs to expand massively to accommodate electric vehicles and other new technologies. Its absolute emissions, therefore, may need to go up, at least in the short term. Most of the large banks do have intensity targets for the power sector and some, most recently Citi, have set intensity targets for automotives, cement, real estate, and other industries.

Another risk of absolute targets for oil and gas, Rothstein said, is that they incentivize banks to sell off loans for high-carbon projects — a pipeline, for example — to less scrupulous banks. “That may help the bank’s target, but it doesn’t help the world,” he said.

The View From Paris

La Banque Postale, a midsize public bank in France, only tracks its financed emissions on an intensity basis, CSO Adrienne Horel-Pagès told me last week. But starting in 2022 it required oil and gas clients to have a transition plan approved by the Science Based Targets initiative, an independent oversight group, to receive financing. Because no oil and gas company has such a plan, none get financing; in the RAN report, La Banque Postale’s financing tally dropped from $267 million in 2021 to zero last year.

Notable

- One area where most banks are making progress is on coal financing, the RAN report concludes. Of the 60 largest banks, 47 exclude financing for coal projects and 39 either have ended or are phasing out general corporate financing for coal companies. The exception is in China, where no bank has placed restrictions on coal finance.