The Scoop

The Intercept, the left-wing U.S. newsroom that’s been a thorn in Joe Biden’s side and a hub for pro-Palestinian coverage, is nearly out of money and facing its own bitter civil war, with multiple feuding factions battling for power and two star journalists trying to take control.

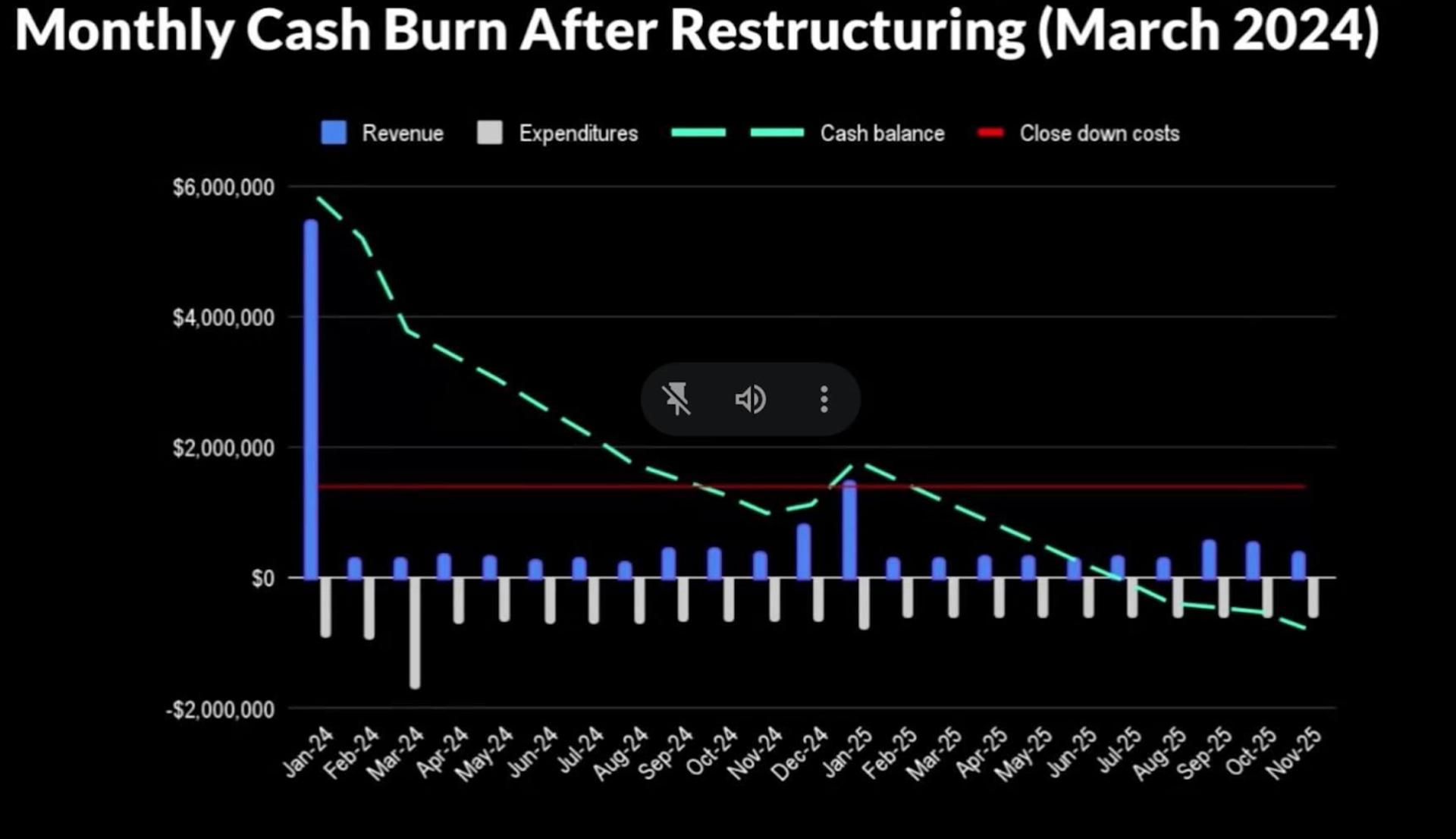

At the heart of the crisis is a nonprofit whose founding donor, Pierre Omidyar, decided in late 2022 to end his support for the organization. Now spun off from Omidyar’s First Look Media, The Intercept is losing roughly $300,000 a month, is on track to have a balance of less than a million dollars by November — and could be completely out of cash by May 2025, according to data shared internally in March.

The Intercept’s CEO, Annie Chabel, told Semafor in an interview this week that those projections were a worst-case scenario, and that the Intercept had a “stretch revenue goal that would allow us to continue into a longer horizon.”

The Intercept was born a decade ago in a very different moment for media and politics. Two of its founders, Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, broke the story of Edward Snowden’s leaked surveillance files in 2013, which reshaped how Americans thought about the government and their privacy. Omidyar, a leftish billionaire with no known appetite for political combat, rapidly pledged deep support for an organization that would combine that anti-establishment mission with a combative form of online journalism born out of Gawker Media.

A decade later, American politics are almost unrecognizable. Greenwald quit in fury to make quixotic allies on the right. Liberal donors have lost their taste for party infighting as the specter of Donald Trump looms, while voices further left are promising to punish Joe Biden over his response to Gaza.

Those factors frame a crisis that comes even as the organization is riding high among its readers for its aggressively pro-Palestnian coverage. The Intercept has broken stories about American diplomatic cables warning of a “catastrophic” Israeli invasion of Rafah, infighting in the philanthropic world, and tensions on campuses, in art galleries, and inside US newsrooms over the war in Gaza. It has picked fights with The New York Times and become a home for harshly anti-Israel voices rarely seen in U.S. media.

But tensions between the outlet’s star reporters, its founders, and its four-person nonprofit board are threatening to unravel it.

In this article:

Know More

Many of the Intercept’s journalists direct their ire at Chabel, a longtime nonprofit executive.

Chabel joined the Intercept at a transition moment for the organization. In 2022, First Look Media had offered a $12 million grant to help the publication spin off — about half of what Intercept leaders had asked for. The publication’s editor-in-chief, Roger D. Hodge, said he told the organization’s board that he did not believe the grant was enough, and they should wind down the Intercept and give staff as generous a severance package as possible. Chabel, who had initially joined the organization as a consultant to manage expenses and oversee the spinoff, helped convince First Look Media to up its grant to $14 million, and presented what appeared to be a financial path forward for the organization.

When staffers convened in October last year for a meeting at the organization’s New York offices, its leadership had what staff interpreted as good news. Now the organization’s CEO, Chabel was overseeing the new financial support model, which would rely on both small-dollar donors and major gifts from philanthropic individuals and organizations. While she wouldn’t commit during the meeting to not laying off staff in the future, Chabel told employees that the organization was stable and appeared to be on target to meet its fundraising goals.

Editorially, world events had reinvigorated The Intercept and given it renewed purpose. The progressive publication’s disdain of Israeli military action and sympathy for the Palestinians distinguished it early in the Gaza war from many major American news outlets. And its distance from the Democratic establishment helped it break a number of stories about the rift within media organizations, liberal politics, and the art world over both U.S. domestic issues and Israel’s military operations in Gaza. That coverage resonated with its core audience of readers and supporters: The Intercept’s membership team boasted to staff that it had exceeded some of its targets in the months following Oct. 7.

But while the scoops yielded small-dollar donations, the organization’s leadership struggled to find the big money needed to keep it operating. Privately, executives acknowledged that while philanthropic donations had doubled between 2022 and 2023, from $488,000 to $867,000, they still had fallen short. In February, the publication laid off 30% of its editorial staff.

It also fired Hodge. The relationship between the then-EIC and Chabel had been deteriorating for months, after Hodge told Chabel that he would not lay off any more staff. Two sources told Semafor she was also frustrated by his lack of enthusiasm for working more closely with the business side. Chabel raised her concerns to the organization’s board of directors, to whom Hodge reported directly, and the board voted unanimously to oust him.

Hodge’s ouster and the increasingly troubled financial picture also created an editorial power vacuum. After the board fired Hodge, Chabel received approval to restructure the organization, requiring a new editor-in-chief to report up to the CEO, rather than directly to the board. She then asked deputy editor Nausicaa Renner and senior news editor Ali Gharib to serve as interim co-editors-in-chief while they searched for a new top editor. Both declined, and Renner resigned.

In a statement to Semafor, Renner said that she found the editorial restructuring “disturbing,” arguing that Chabel’s leadership had altered the coverage and threatened editorial independence.

“Editorial hires and priorities should not be determined by the CEO,” she said of Chabel. “No matter what her politics are as an individual, the effect of her cuts and leadership is to quiet an outspoken outlet on Gaza.”

The site’s veteran journalists offered an interim path forward. Several staffers proposed that a four-person committee be formed to run the publication’s editorial side while it searched for a new top editor: Gharib, co-founder Jeremy Scahill, Washington, D.C. bureau chief Ryan Grim, and editor Maryam Saleh. The board rejected the idea.

In March, Chabel announced to staff in an email that it had been approached by several unnamed employees who put forward a proposal for “a transfer of the intellectual property of The Intercept to a new entity.”

“We are engaging with it seriously,” Chabel wrote.

The email confused and alarmed staff, prompting Grim to respond with a clarification. He and co-founder Jeremy Scahill had suggested that the four-person board of directors resign, turning the operation over to the duo and remaining staff.

“Our motivation is firmly rooted in a deep commitment to sustaining the work of a media outlet that has served for more than a decade as a vital source of hard hitting journalism and an unwavering dedication to holding the powerful to account,” he wrote.

But the board wasn’t swayed by this idea, either. In an email several days later, Grim said that he’d been “informed by the board that our proposal has been declined.”

Some of the internal battles have spilled into public view. In March, The Intercept’s editorial union released a statement excoriating leadership for its fundraising efforts. Chabel “had one job to do, and she failed,” the unit said.

Those tensions have run even higher internally. During a meeting earlier this year, Scahill exploded at Chabel, saying she should resign. Other recent decisions by the organization’s leadership have irked remaining staff. As Semafor first reported, during an all staff meeting on Thursday the publication told employees that it had hired former Los Angeles Times assistant managing editor Ben Muessig to be the interim editor-in-chief — who, according to multiple sources familiar with the selection process, was not employees’ first choice.

And there is little internal consensus on how to move forward. Grim and Scahill are two of the outlet’s longest-serving figures, with Grim leading high-profile coverage and Scahill helming its podcast. But their plan would inevitably involve deep cuts and layoffs. (Other staffers pointed out to Semafor that, on the current trajectory, they’ll likely all lose their jobs anyway.)

Some of Chabel’s allies, meanwhile, blame Hodge for the current mess, saying the publication missed an opportunity to align the newsroom with the nonprofit’s fundraising imperatives. Hodge told Semafor he found that sentiment confusing.

“It’s simply not true that I resisted working with the fundraising operation,” he said. “I spent untold hours talking to them about the journalism and writing memos and have been helping to brainstorm how they could describe the work we’re doing. I spent way more time doing that than editing pieces.”

Max’s view

The Intercept’s mission is clearer now than it has been since the 2020 Democratic primaries, in which the publication aggressively attacked moderate Democrats from the left with election-shaping scoops. That string of stories terrified (or at least annoyed) centrist Democrats, and helped shape the publication’s image as the most overtly progressive and leftist national news outlet that consistently broke news. Now, The Intercept’s unapologetically hostile view of Israel’s post-Oct. 7 military operation in Gaza has galvanized its readers and supporters, who have responded by helping the publication set internal records for small-dollar donations.

But the notion that a radical, anti-establishment newsroom was going to rake in big checks from liberal American donors now seems fanciful. The Intercept burnished its reputation on the left by aggressively reporting on big-money liberal donors who backed more moderate candidates. These same figures are often major players in the philanthropic space, and of course have balked at donating.

Room for Disagreement

Chabel acknowledged that while “it’s not a surprise that there are some traditional funders who are not going to be interested in our particular brand of journalism,” she believes it takes time for any nonprofit to find major donors. The Intercept, she said, occupies a “unique place” in the news landscape that can still appeal to certain major funders, even if they don’t agree with everything it publishes.

“I think a lot of donors care about who is in power and the power is questioned, regardless of whether it’s left or right,” she said.