The Scoop

The private equity firm Carlyle Group is courting artificial intelligence-focused data centers as anchor customers for a series of large solar power farms it’s building in the Arizona desert.

Two years after Carlyle founded its own renewable-energy development company, Copia Power, construction is underway on its first project: a $2 billion, 1.5-gigawatt solar-and-storage project outside of Phoenix. A second, similar project is expected to break ground nearby later this year, and a third 1.5-gigawatt facility is in development for the near future. Although the customers Copia Power initially locked in are fairly routine — the local utility and the hardware chain Lowe’s — the company is now shifting its focus to target tech companies, which have emerged as the U.S. power market’s most voracious buyers of low-carbon electricity, Pooja Goyal, Carlyle’s chief investment officer for infrastructure and head of renewables, told Semafor.

“We knew there was going to be a lot of demand from corporate customers for the energy from these projects,” she said. “But we definitely did not take into account the demand pull from AI that is happening right now. That’s become a major accelerator to the original investment thesis.”

In this article:

Tim’s view

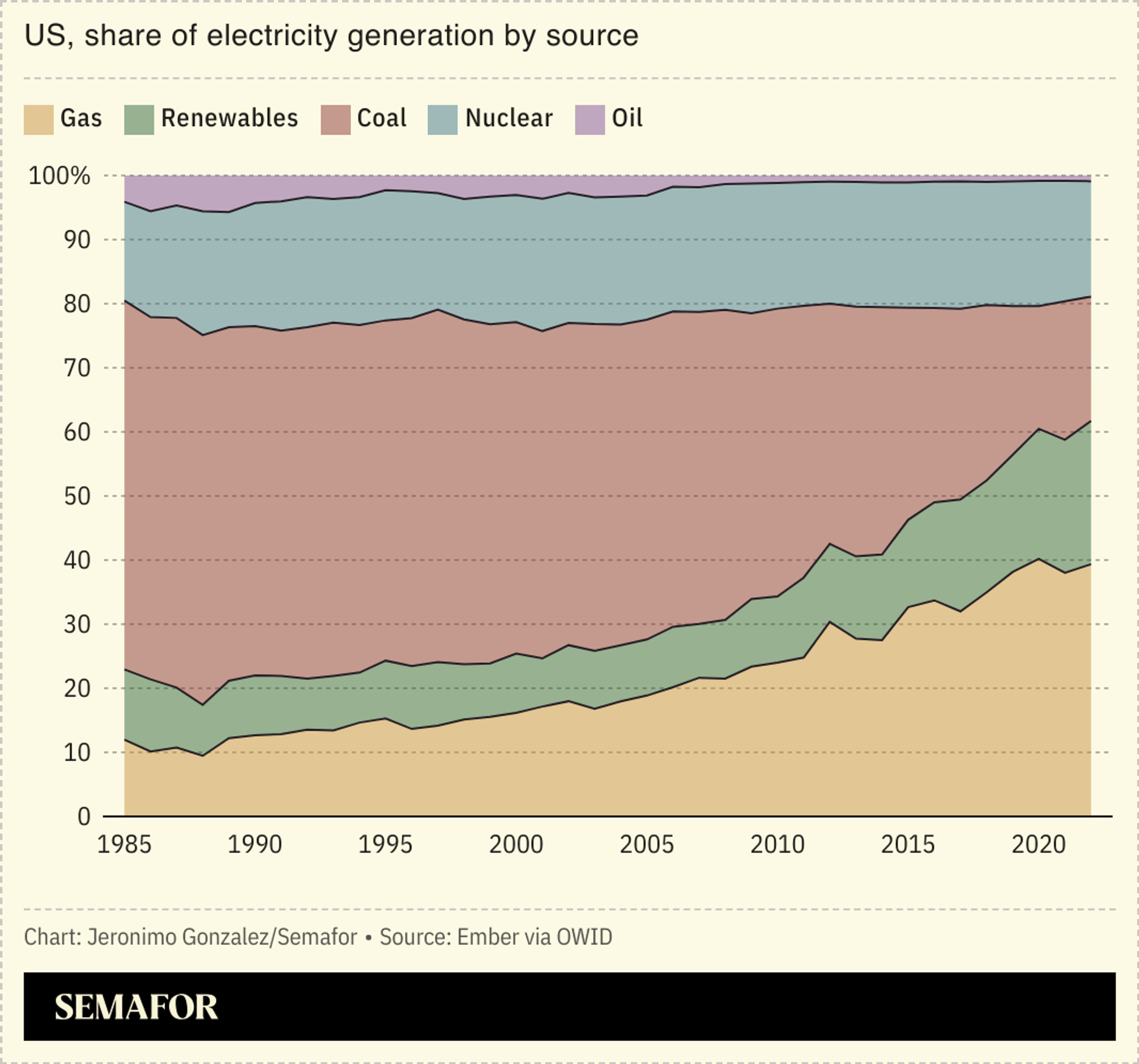

Carlyle’s multibillion-dollar gamble on renewable energy is unconventional — it’s rare for PE firms to found their own companies, rather than invest in existing ones. But it was based on a conviction that the reliable-but-sleepy electricity market of the last few decades is about to get a lot more interesting as EVs, the decarbonization of homes and businesses, traditional data centers, and now AI drive a big increase in power demand. If Carlyle can prove out a model for reaping PE-sized returns selling power to tech companies that are willing to pay a premium for carbon-free electrons, it would help ensure that the AI power boom doesn’t come at the expense of the climate — and make renewables more attractive to a corner of Wall Street that is still heavily invested in fossil fuels.

There’s an added sense of urgency in the AI power boom from the fact that it takes longer to build large power infrastructure than it does to build a data center. Traditional utilities tend to be slow-moving, bureaucratic, and heavily regulated, all qualities anathema to Silicon Valley. As a result, tech companies are more often trying to cut out the middleman; OpenAI’s Sam Altman, for example, is working to take the small nuclear reactor startup Oklo public in part to facilitate the use of nuclear power to run his firm’s massive AI supercomputers.

Goyal’s goal is to plot out new clean-energy farms ahead of demand and then tempt tech companies into building their AI-crunching data centers nearby. Sidestepping utilities and linking clean-power projects directly to data centers will make the power cheaper for buyers and more lucrative for Carlyle, Goyal said. It also bypasses one of the biggest obstacles to the clean-energy buildout: the cost and bureaucracy that come with building transmission lines. Tech companies also tend to be well-capitalized and have good credit ratings, which makes them choice customers for power projects because having a contract with them lowers the cost of borrowing the upfront finance required to build out the project itself.

Carlyle hasn’t yet locked in contracts for its Arizona projects with any tech companies. In the meantime, it’s in competition with renewable energy project developers across the country, which are likewise clamoring to sign contracts with data centers, said Thomas Byrne, CEO of the solar project developer CleanCapital. The whole trend has traditional utilities on edge, he told Semafor. Direct deals between renewables developers and data centers mean lost transmission business for utilities, and to the extent that utilities themselves want to buy more renewable power, they’re increasingly being pitted against tech companies that are able to outbid them — potentially limiting options for the grid to pivot away from fossil fuels.

Quotable

“All the money that has historically poured into oil and gas is going to pale in comparison to what potentially could exist on electricity. This market is going to look extreme compared to anything else.”

— Evan Caron, chief investment officer at Montauk Climate, an electricity-focused startup incubator.

Room for Disagreement

Carlyle’s AI power play isn’t entirely clean: Goyal said the company is working on plans to include small gas-fired power plants alongside some of its future data center projects to ensure 24-hour reliability, a priority for data centers.

Private equity in general has moved more slowly than banking in setting net zero targets and guidelines for their fossil fuel financing, said Jim Baker, executive director of the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a nonprofit watchdog group. Carlyle in particular, he said, has lagged its peers, and invests about $16 in fossil fuels for every dollar it invests in renewables. “They’ve adopted a ‘have their cake and eat it too’ approach, in terms of investing in renewables where it’s opportunistic to do, but also continuing to invest in oil and gas exploration and production.”

Notable

- Bullish electricity demand forecasts because of AI could be used by utilities to justify a buildout of fossil fuel power plants that aren’t really necessary, Robinson Meyer writes in Heatmap: “The real danger is not that we’ll run out of power. It’s that we’ll build too much of the wrong kind.”