The Scene

BENIN CITY, Nigeria — One of the most recognizable landmarks when flying into the ancient city of Benin in Nigeria, home of the prestigious Benin bronzes, is the red cylindrical National Museum.

On a recent visit on a Saturday, the museum was unexpectedly quiet, with just two visitors during the two hours I was there. It was the first visit for both of them, one a Benin City resident, and they had been hoping to see Benin artifacts that had been returned to Nigeria. The museum’s curator, Mark Olaitan, said the returned items “haven’t been mounted or exhibited yet.”

The museum visitor numbers have risen slowly since the end of restrictions on movement imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Olaitan predicted confidently that the museum would soon be overwhelmed by the volume of visitors when exhibitions featuring the returned items are fully opened to the public.

Know More

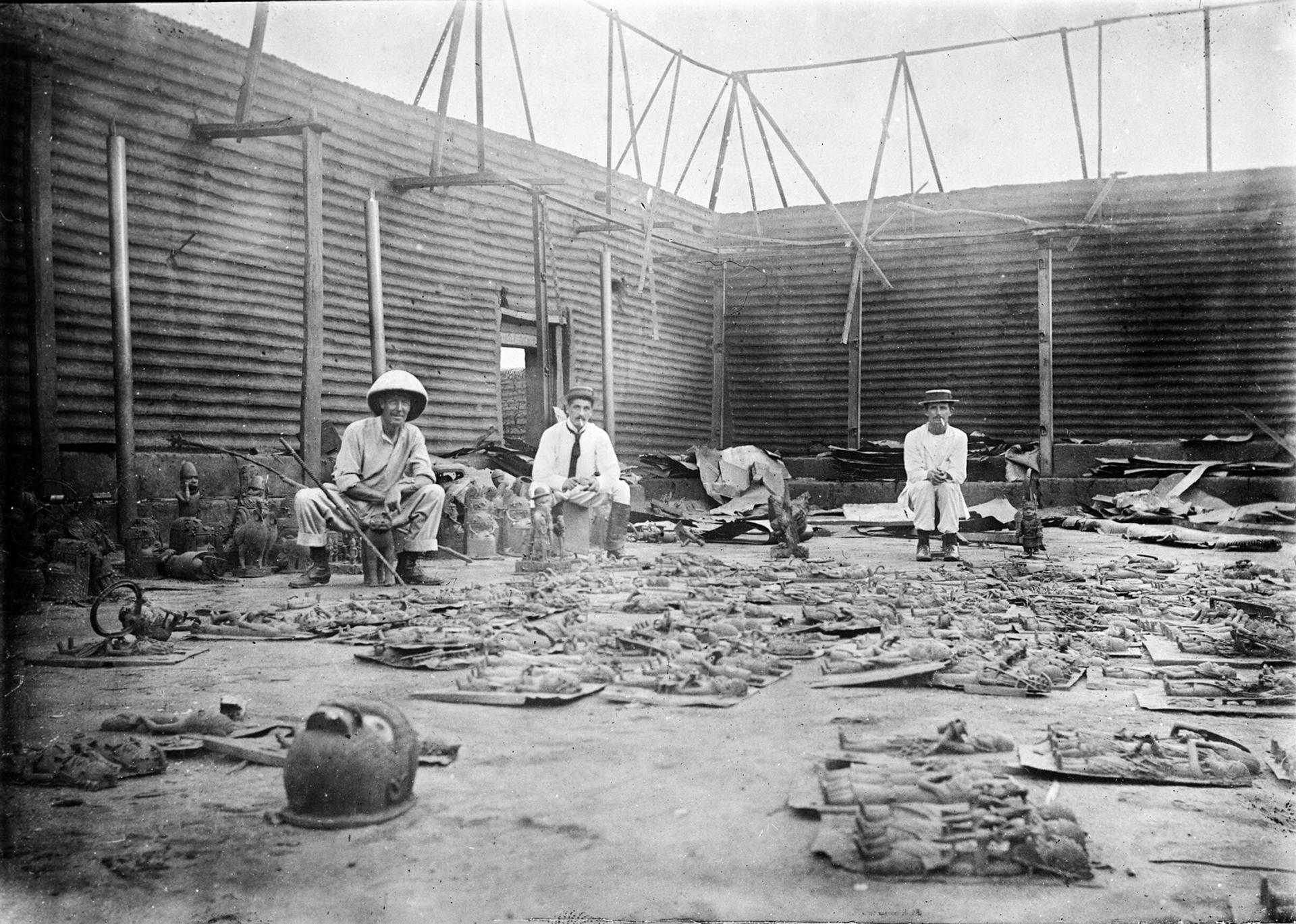

The majority of African artifacts in museums are held outside Africa, with more than half a million in European institutions alone. Over 4,000 objects looted from Benin City by British soldiers in 1897 (pictured below) — commonly referred to as the Benin Bronzes — are among the most notable of these artifacts. They have been at the forefront of campaigns calling for the restitution of African artifacts.

Museums and universities in Europe and America last year began returning looted Benin artifacts in their collections to Nigeria, nearly a century after traditional ruler Oba Akenzua II championed the demand for restitution in 1935.

Last year the governments and intuitions of the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany transferred the “ownership” of about 121 Benin artifacts to Nigeria. The transfers often involve agreements whereby some of these objects remain in these foreign museums on loan. Olaitan said agreements signed by Nigeria with other countries include “capacity building, staff training, [and] exchange programs” that would help improve Nigerian museums.

The global campaign for the return of the bronzes has attracted investment to Edo state to build a cultural district in Benin City. The investment includes the building of the Edo Royal Museum, the Edo Museum of West African Arts (EMOWAA) with the EMOWAA Pavilion (research and educational facility), and Benin City Mall amongst other features.

Olaitan is optimistic that the construction of these buildings as well as the staffing of these institutions will create job opportunities and attract visitors to the state, particularly leisure tourists.

Uwagbale’s view

The return of artifacts like these is an opportunity for African countries to reap huge economic benefits. Governments can boost revenues through museum attendance as well as through money spent by visitors, from hotel accommodation to restaurants and souvenir shops. A multi-layered domestic and international tourism industry also creates jobs.

The United Kingdom has shown the economic benefits of displaying cultural artifacts — many of which were plundered from Africa. In just three months between April and June 2022, some 8.3 million people visited the country’s 15 government-sponsored museums and galleries including the British Museum, which has the single largest collection of Benin bronzes in the world. Those visitor numbers are still down from between 11 million to 14 million each year before the pandemic. These museums and galleries contributed £73 million ($88 million) to the British economy in June 2022.

The Edo state government is working on ways to replicate that success once the items have been returned home. The state, leveraging its rich cultural heritage, launched a tourism master plan in September 2022. The plan includes the development of a tourism corridor connecting about 72 different tourism sites including a wildlife park, and cultural and natural sites, with the government targeting 2 trillion naira ($4.3 billion) of tourism revenue in the next 10 years.

“The artifacts being returned to Africa present a strong opportunity to develop cultural heritage tourism seriously,” said Adunola Okupe, the CEO of tourism consultancy Red Clay Advisory which has experience across West Africa. “There is a strong multiplier effect that will generate even more returns to other industries than tourism alone.”

The View From Cotonou

The modern-day Republic of Benin, to the west of Nigeria, is not to be confused with Nigeria’s Benin City. The West African country, which was colonized by France, was once dominated by the Dahomey Kingdom which produced many great art works. Today Benin Republic is developing its own cultural heritage tourism.

With the return, in November 2021, of 26 artifacts looted by France’s colonial troops, its government announced the creation of the Museum of the Epic of the Amazons and Kings of Dahomey in Abomey to house the items returned along with a collection of some 350 art objects.

The project includes the rehabilitation of four royal palaces that attracted a grant and a loan $38 million from the French Development Agency (AFD). A free exhibition last year which lasted several months reportedly attracted more than 200,000 visitors with domestic visitors making up 90% of the total.

Room for Disagreement

While there’s been much public and government support in both African countries and former colonial powers for the return of artifacts, there has been some push back. Some European curators have gone as far as questioning if these valuable items would be well preserved in countries without a strong museum tradition or investment.

There has been displeasure from unexpected quarters as well. An African-American campaign group filed a lawsuit in November 2022 to stop the return of some Benin Bronzes from the Smithsonian Museum to Nigeria, arguing that returning the bronzes would deny them the opportunity to experience their shared culture and history. They claimed the artifacts are also part of their heritage as descendants of an enslaved person from the region controlled by ancient Benin.

Notable

- While the push to return artifacts feels very much a late post-colonial movement in the age of Black Lives Matter and South Africa’s Rhodes Must Fall — it is not. Back in the sixties, the decade of independence for many African countries, there was a strong push for the return of artifacts but for a variety of reasons it had faded by the eighties.