The News

The annual meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC, last week yielded disappointingly little progress on climate finance, climate diplomats warned, opening what is likely to be a contentious buildup to a major showdown at the COP29 summit in November.

Headlines focused on the US, Japan, and several European countries collectively contributing an additional $11 billion to the World Bank’s lending capacity, and how that fell far short of the estimated $1 trillion per year that developing countries need to adapt to climate change. But an even bigger issue looms, one which received even less attention from rich countries, and which is in many ways more vexing: Developing countries face a crippling mountain of debt that — regardless of how much their richer peers hand over — will derail any efforts to combat climate change.

And although leaders like Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley have spent the last several years articulating detailed solutions, and despite World Bank President Ajay Banga having expressed much more eagerness to address climate change than his predecessor, last week’s meeting closed without any concrete steps.

Tim’s view

The fundraising shortfall is, to some extent, a distraction.

Certainly, more donations from rich countries will be hard to come by in a year with two major wars, escalating trade tensions, and a high-stakes election in the US. In an interview, Majid Al Suwaidi, a longtime United Arab Emirates climate diplomat who worked as director-general of last year’s COP28, said that he was pleased to hear a more substantive discussion of climate from the finance ministers of wealthy countries at the World Bank meeting. But until those countries are able to significantly step up their contributions to climate finance, he said, it will be hard for them to regain the trust of their peers in the global south.

“You haven’t seen real transformation of the institutions,” Al Suwaidi told me. “It is a slow process by nature, but the problem is, we don’t have that time.”

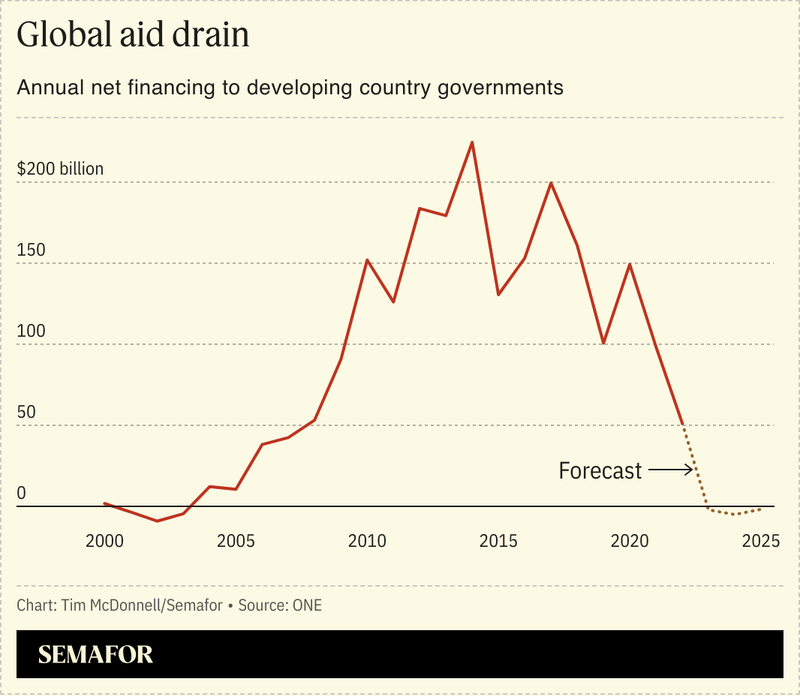

But far more important is a worsening debt pile in developing nations. Last year, for the first time in two decades, developing country governments became net contributors to international finance flows, because they collectively paid more to service debt held by other governments, development banks, and private lenders than they received in new loans and development aid, according to a report last week by the advocacy group ONE. This year, the report projects, developing countries will lose $50 billion on net, because of debt repayments.

Until that hole is plugged, it doesn’t make much sense to talk about new World Bank lending, said Michael Jacobs, a senior fellow at the think tank ODI.

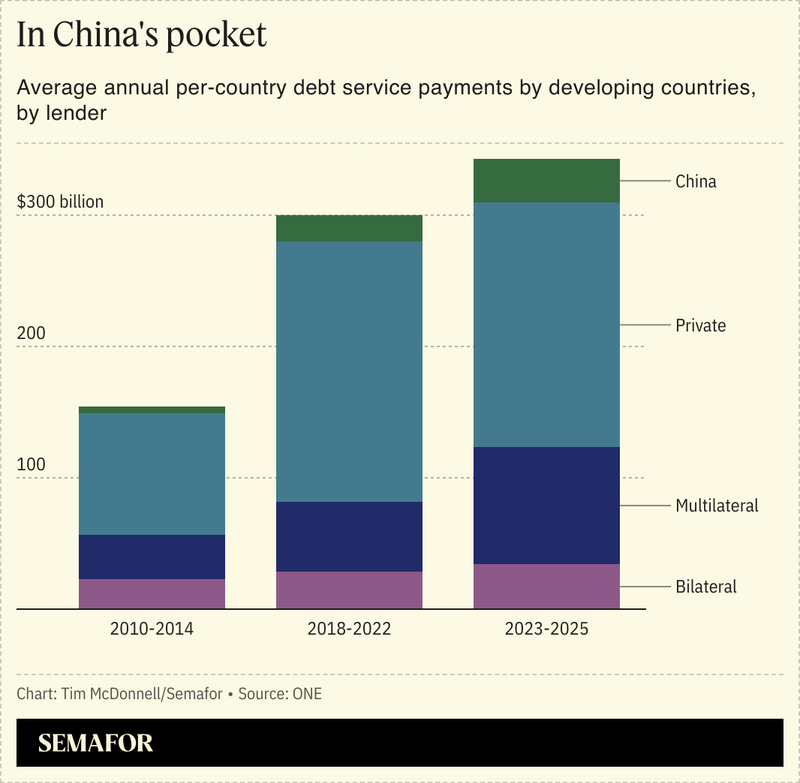

“The elephant in the room is that developing countries are actually experiencing a debt crisis,” he said. “So there’s something very perverse about trying to lend a very highly indebted country more money, when what will actually happen is that the money will just flow straight back out again, to the global north, or to China or to private creditors.”

Jacobs is an advisor to a new committee on the linked crises of debt and climate, which was set up by the governments of Colombia, Kenya, France and Germany, and met for the first time on Saturday. The committee will spend the next year cooking up ways to alleviate developing countries’ debt burdens and thereby save them, collectively, hundreds of billions of dollars they can then spend on more urgent climate and development priorities.

Those solutions include pausing debt repayments after natural disasters, canceling them altogether in exchange for climate actions by the debtor country (so-called “debt for climate swaps”), transferring debt to private lenders at lower interest rates, or even converting debt into carbon credits, which the lending country could count against its carbon footprint. The committee will also push for development banks to do more lending in local currencies, rather than the US dollar, so that developing countries don’t see their payments spiral up when US interest rates are high.

Climate-related debt management plans today “tend to be all very one-off and bespoke and difficult,” Jacobs said. The committee hopes to streamline them, but Jacobs said Banga is up against his own staff — whose chief incentive is to get World Bank money out the door, and thus are disinclined to partner with other lenders or avoid creating new debt — and against the US and other top World Bank shareholders, which are loath to accept any kind of reform that could give China more influence (for example, by letting it dictate new terms for debt it is owed) or put themselves on the hook for more money.

“There’s a blame game happening here,” he said. “The shareholders will say in public that the [World Bank] management isn’t moving quickly enough. And the management says ‘yeah, but that’s because you don’t agree with any of our proposals’.”

The View From Azerbaijan

Debt will likely be on the table at COP29 in Baku this fall, but the biggest headline of the summit will be a fundraising number. Delegates are meant to come up with a new total climate finance goal to replace the $100 billion target that has been on the table since 2009. Depending how you count, that target has either been met or is still tens of billions short. Either way, the number was always a political convenience, rather than a realistic assessment of the costs of climate adaptation and mitigation, which are at least an order of magnitude greater. By the end of COP29, there may be a new number (in private, some diplomats joke it could be just $101 billion), as well as new agreements on how to distribute it, how much of it might come from the private sector, and what China’s role as a contributor should be. Preliminary negotiations on those questions are underway in Colombia this week, but Jacobs said not to hold one’s breath for a sweeping conclusion in Baku, and that the talks could easily spill into next year.

“To be perfectly honest, no progress has been made at all and there is not even a consensus on what this goal is meant to cover,” he said. “The positions are very far apart, which means there’s some jeopardy around COP29.”

Room for Disagreement

Ani Dasgupta, president of the World Resources Institute, told me onstage during Semafor’s World Economy Summit last week that because progress on both debt reform and fundraising are likely to be slow, development banks need to do more in the short term to make their in-house policy expertise more accessible to developing country governments, in the interest of adopting domestic policy changes that can draw in more private investment from overseas.

“I’m afraid too much of the discussion is just about volumes of money, and not about how to help countries restructure and rethink their economies,” he said, since it will be impossible to reach any realistic climate finance goal without much or most of the money coming from private investors. For now, the push by the US and Europe to “onshore” their climate tech industries may have the opposite effect, some economists warn, drawing capital away from the global south.

Notable

- In the meantime, some lawmakers want the World Bank to roll back its investments in fossil fuels. In a letter last week to the bank’s executive board, three Democratic US senators complained that its “direct and indirect support for fossil fuel projects supercharges the climate crisis while decreasing lending capacity, leverage capital, and availability of climate financing for developing countries.”