The News

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is expected to propose as early as this week a plan to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. A previous stab at the idea by the Barack Obama administration was thrown out by the Supreme Court last year.

U.S. President Joe Biden is trying to get his own version greenlit — and its odds of success look much better.

Tim’s view

The world is a very different place now than when Obama’s Clean Power Plan was introduced in 2015. Although Biden’s proposal is certain to face legal challenges, economic conditions are aligned for it to make an immediate impact on investment decisions with long-term carbon consequences.

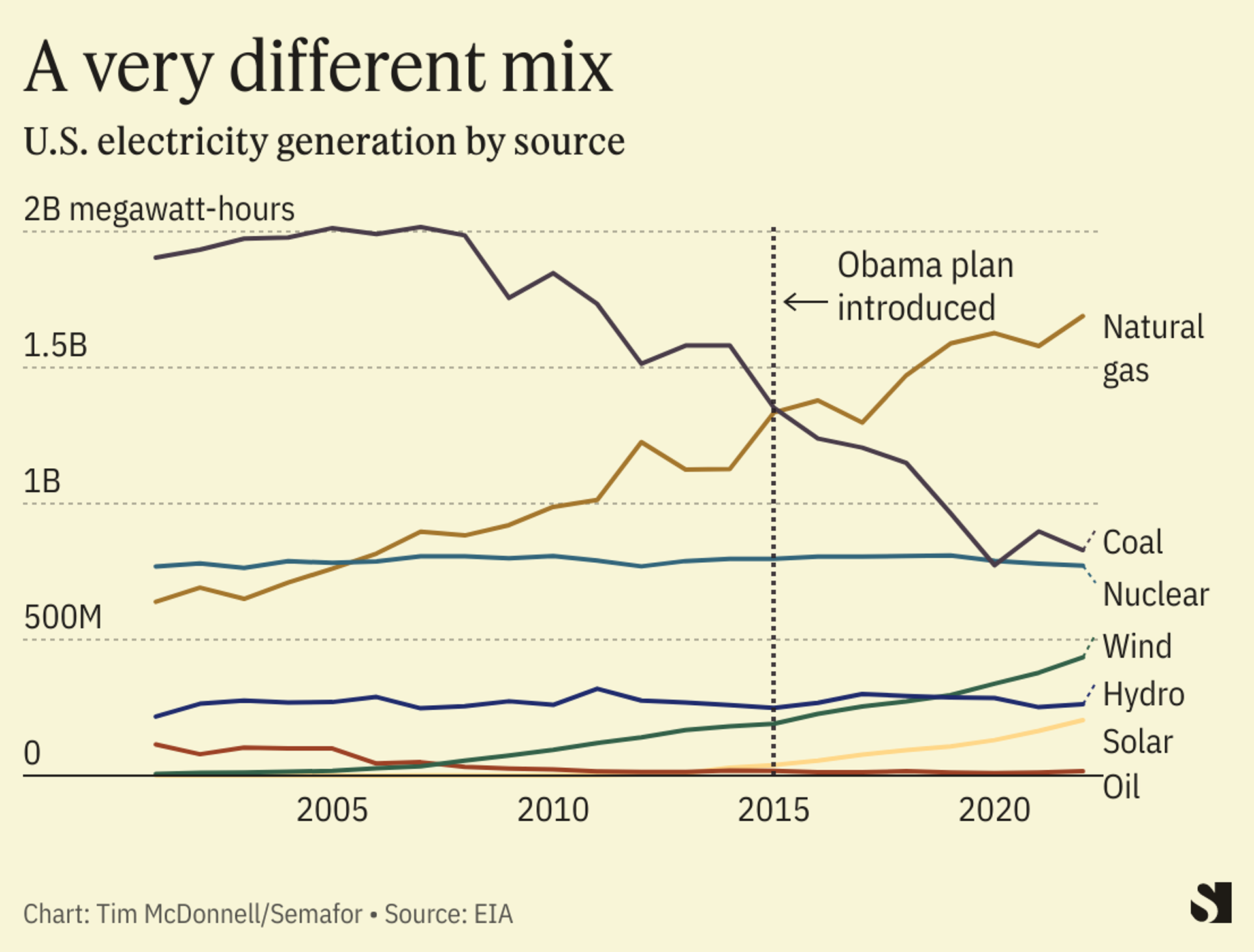

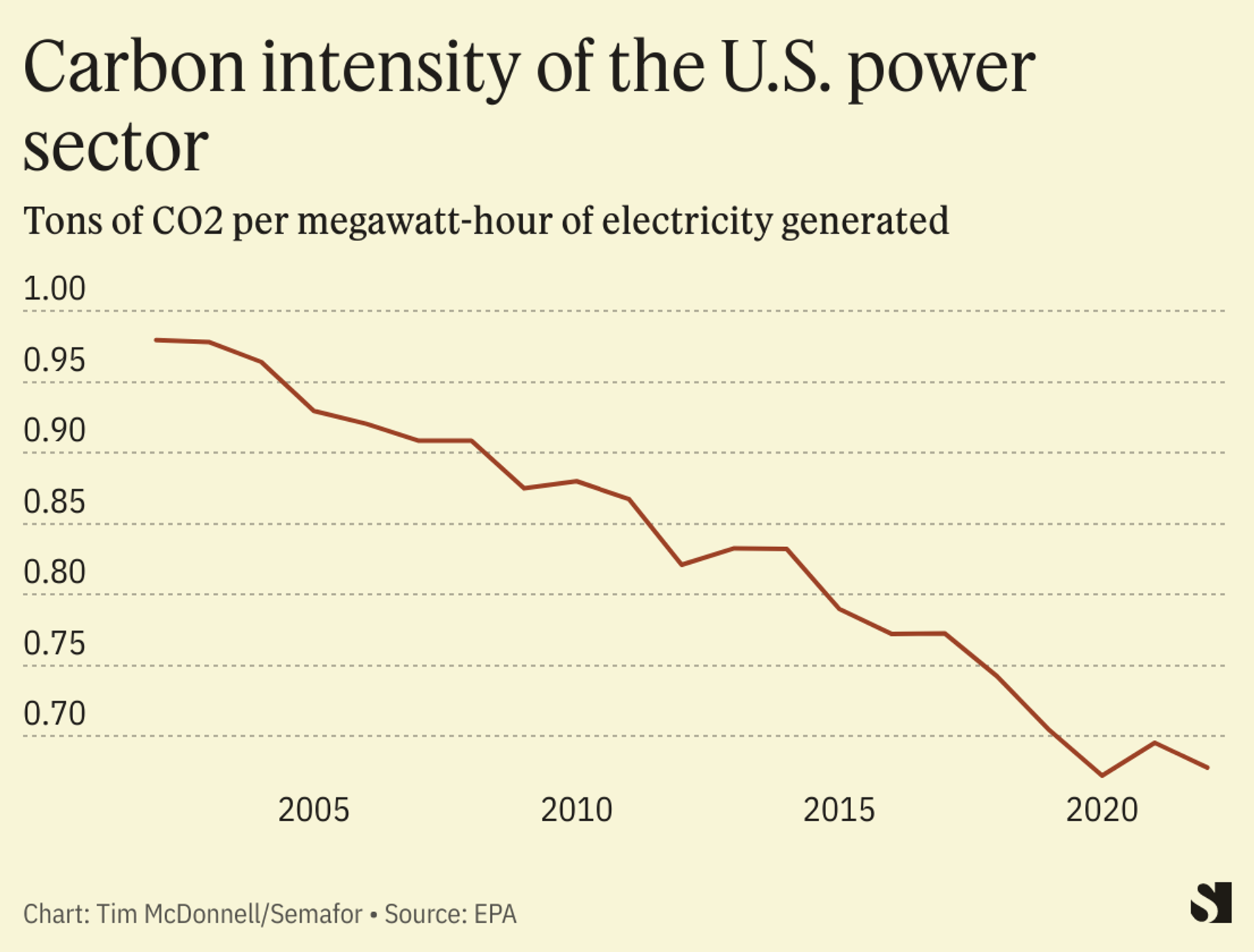

The U.S. electricity system, the country’s second-highest source of emissions after transportation, is already much less carbon-intensive than it was a few years ago, mostly because natural gas has swapped places with coal in the fuel mix.

Power-sector decarbonization is only gathering pace because of clean energy incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act. With no further policy changes, the IRA is expected to drive coal down to 3-7% of the electricity mix by 2030, from about 33% in 2015, according to the think tank Rhodium Group. The legislation is also projected to lower total electricity emissions by up to 80% from 2005 levels by 2030.

IRA tax credits will allow regulators to set more stringent carbon reduction targets because the anticipated cost of compliance will be much lower, particularly because of a credit worth up to $85 per ton for CO2 that is captured from a power plant and buried.

“The economics of the energy transition are driving the power sector to meaningfully reduce emissions,” said Ben King, associate director of the energy and climate practice at Rhodium Group. “However, without any regulatory guardrails, gas continues to get built and to contribute meaningful emissions. The next frontier in power sector emissions reductions is keeping gas emissions down.”

Although full details of the Biden plan haven’t been released, Bloomberg reported this week that it is designed to avoid the legal pitfalls that doomed Obama’s plan. The Obama version set a carbon intensity (tons of carbon emitted per megawatt-hours) target for each state, and though it left it up to the state’s policymakers and utilities to decide how to get there, the EPA included a push to switch from fossil fuels to renewables. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled this approach effectively meant the EPA was making choices about a state’s energy mix, exceeding its authority.

Instead, the court said, the EPA can only set emissions limits for individual power plants. That’s what Biden’s plan sets out to do, and would push the operators of coal- and gas-fired power plants to install carbon-capture systems, mix gas with hydrogen, or shut down. A low-carbon electric grid is a prerequisite for other elements of U.S. climate goals, such as increasing sales of EVs.

Biden’s plan may still get tied up in court, or jettisoned by his successor. But utility executives — who actually supported the EPA in the Supreme Court case that brought down Obama’s plan — have already seen the writing on the wall. Sooner or later, power plant emissions will be forced down. From an investment and capital spending perspective, that means carbon capture is clearly a juicy opportunity, and giant new fossil fuel infrastructure is a growing risk.

“When utilities go before their regulatory commissions, they’ll be asked whether it’s a good idea to invest in a big gas plant when it might get shut down well before it can be paid off,” King said.

Room for Disagreement

Technologically, carbon capture is far from a slam dunk. The only large U.S. power station equipped with the technology, the Petra Nova coal plant in Texas, has been a billion-dollar debacle for its investors and is often uneconomic to operate. Environmental groups also argue that the use of carbon capture merely prolongs the market for oil and gas drilling, and that it will rarely, if ever, be cheaper than building renewables. New regulations will force power plant operators to decide whether IRA tax credits are enticing enough to invest in the R&D needed to deploy power plant carbon capture effectively at scale — or if it still makes more sense to build a wind farm instead.

The View From Europe

The new regulations will also set up a new test of the effectiveness of U.S. versus European climate policy, following recent trade tensions caused by the IRA and EU carbon border tariff, the former of which Europe argues is protectionist. Europe’s power plant emissions are regulated via its carbon cap-and-trade market, which has up to now set a carbon credit price too low to make much of an impact. The region’s power-sector emissions intensity has fallen by about 20% since 2002, compared to 30% in the U.S. But EU carbon prices are set to rise over the next few years as the border tariff kicks in, and the geopolitical imperative to drop Russian gas imports is driving a boom in renewables. Last year, wind and solar were the region’s top source of electricity for the first time.

Notable

- One other obstacle for decarbonizing the U.S. power sector is the workforce. The New Yorker this week has a deep-dive into the shortage of electricians in the U.S., and how the labor force will need to change to actually build the projects enabled by the IRA.