The Scene

On a sunny spring day at Rob and Jo Hodgkins’ farm in southern England, sheep were being led, one by one, into metal boxes resembling oversized washing machines. Each of the 120 animals stayed in the chambers for 50 minutes — to have their emissions measured.

The tracking program is the first step in a long journey for the Hodgkinses, who are trying to breed “ultra-low emission” sheep, ones that naturally produce less methane, a potent greenhouse gas that has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

Like other ruminants — hoofed plant-eating mammals such as cattle, goats, and buffalos — sheep belch out methane while digesting food. Up until now research has focused on cows, which emit the most methane. But scientists in New Zealand have demonstrated that methane emissions are in fact a heritable trait among sheep, a finding that serves as the inspiration for the Hodgkinses’ attempt.

Xiaoying’s view

When I went to visit Rob, I expected him to extol the environmental virtues of his efforts. He and his wife are, after all, the first independent farmers in the U.K. to try to breed low-emitting sheep. Instead, he talked me through the commercial imperative, and that makes sense: As with much of the fight against climate change, businesses have to be able to turn a profit to survive and make the investments necessary to reduce their emissions.

Farmers like the Hodgkinses show that the livestock sector — which employs 1.3 billion people worldwide — can be part of the solution to the pressing problem of livestock emissions.

Rob, 43, believes that offsetting carbon emissions and breeding low-emitting livestock will be “a large part of agriculture” in five to 10 years, “a necessity” prioritized by supermarkets and customers. “The purpose of the project fundamentally is to make sure our farm is secure and profitable in the future,” he told me.

His farm keeps 2,300 sheep and produces roughly 70,000 kilograms of sheep meat every year. It is a supplier to the British supermarket giant Tesco, which has pledged to be net zero across its value chains by 2050.

The Hodgkinses, who are working on the breeding project with Agri-EPI Centre, a U.K. government-funded organization, and researchers from Scotland’s Rural College, believe an early start is crucial.

“Whilst at the minute no one is paying us to do this, I believe in 10 years, there will be,” Rob said. “But in 10 years’ time, we will be 10 years behind, so we need to start now.”

Know More

Rob and Jo are able to run this project largely because their sheep are genetically related to a breed in New Zealand, where scientists have spent the past 15 years identifying and breeding sheep with low-methane genetic traits.

The New Zealand program found that after three generations of selective breeding — pairing low-emitting sheep with other low-emissions ones — the lowest-emitting offspring produced nearly 13% less methane than the highest emitters, per kilogram of feed eaten.

Ruminants alone are responsible for around 30% of global methane emissions, and more than 90% of those emissions are burped out. The methane emissions from ruminants largely depend on how much they eat. Compared to sheep, cattle are a bigger source of methane, and more efforts have been made to deal with their burps, ranging from selective breeding to vaccines.

Ermias Kebreab, an animal scientist and professor at the University of California, Davis, told me that scientists have also reduced cattle emissions by targeting the ingredients in their feed. By mixing seaweed into beef cattle’s feed, for instance, his team found they could slash their emissions by as much as 82%.

Quotable

“We need as many tools in the box as we can for being able to reduce methane emissions from ruminant livestock production and safeguard food security at the same time,” Nicola Lambe, a researcher from Scotland’s Rural College, said.

Room for Disagreement

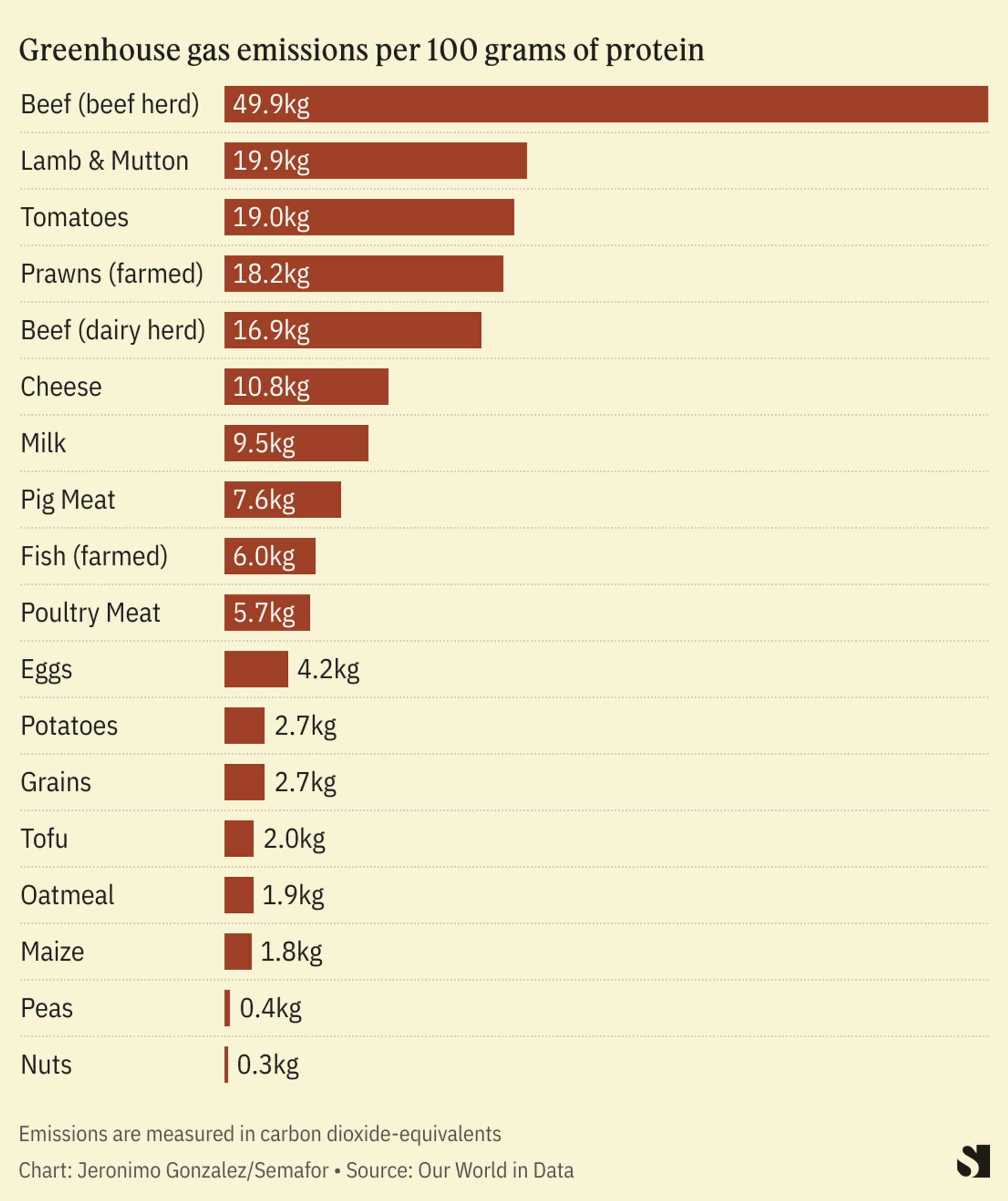

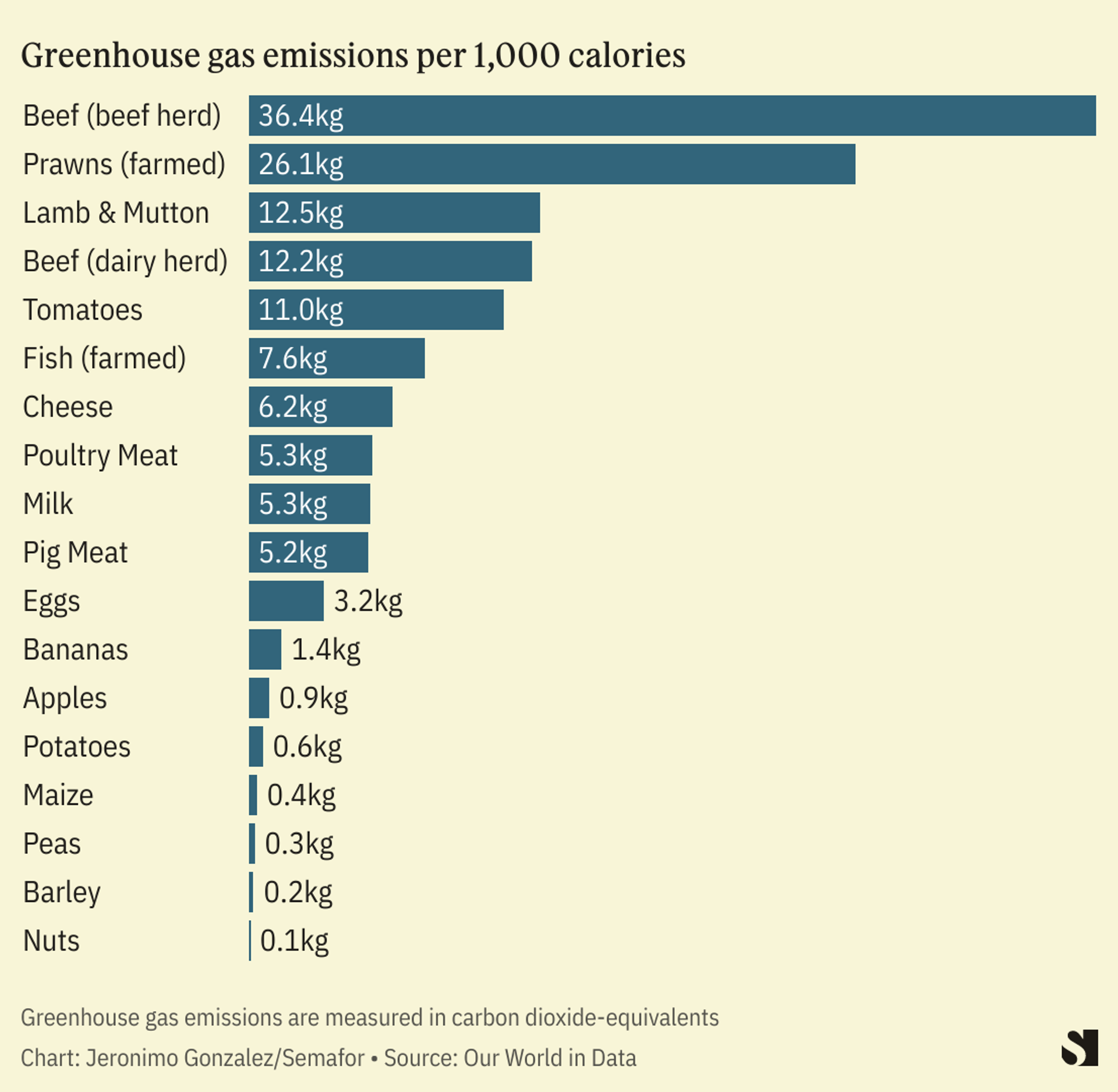

Rather than trying to reduce emissions from meat, a more efficient way to cut greenhouse gas emissions would be to stop eating meat, or at least drastically cut its consumption: That’s the recommendation from a 2019 U.N. report. “We don’t want to tell people what to eat,” an expert on the committee that drafted the report told Nature. “But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

The View From New Zealand

Beef + Lamb New Zealand, an industry group involved in the sheep emissions program, plans to build a genetic evaluation system that will allow all Kiwi sheep farmers to select sheep that produce less methane. So far, more than 20,000 sheep have been measured for their methane emissions in the country, and the number is growing.

Notable

- Last year, New Zealand became the first country in the world to unveil a plan to tax sheep and cow burps in a bid to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but the move has sparked concern from some farmers over the future of their livelihood, as Rachel Pannett reported for The Washington Post.