The News

Tens of thousands of African postgraduate students will no longer be able to bring family members to Britain under reforms to curb migration, in a shift that will force future generations of top students to pursue opportunities elsewhere.

Nigerians will be particularly hard hit by the rule change, which will come into force in January and applies to all foreign students. Students from Africa’s most populous country make up one of the biggest groups of foreign students in the UK and have in recent years brought more dependents — typically children and partners — than those from any other nation.

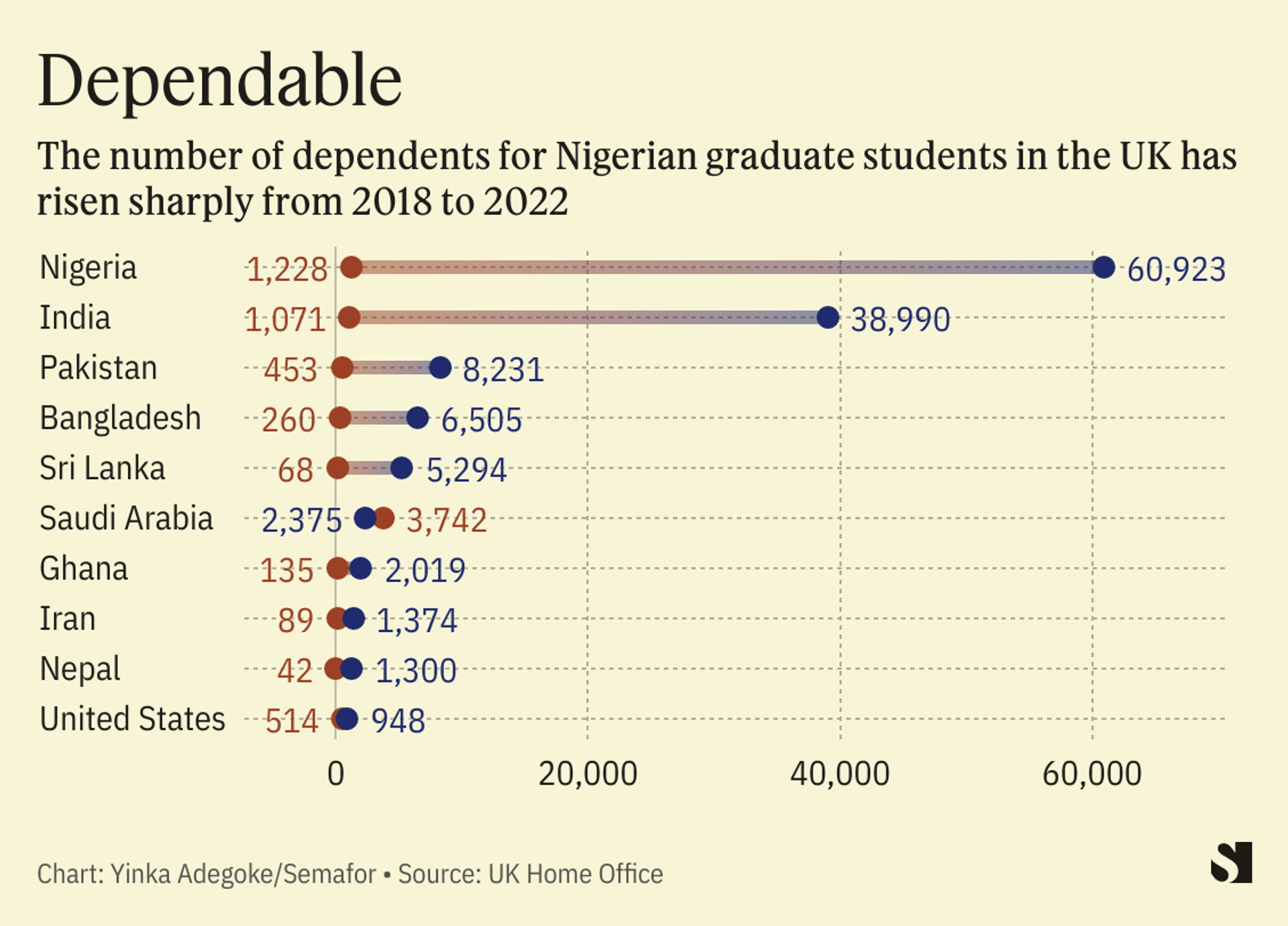

Home Office figures show Nigeria had 60,923 dependents of sponsored study visa holders in 2022. India, the world’s most populous nation, had the second highest number of dependents — 38,990.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s right-leaning government announced the new restrictions earlier this week, ahead of the publication of official figures today that show 606,000 more people moved to Britain than left the country last year — a record high.

Know More

Tuition fee income from non-EU students has grown substantially over the last 20 years, making up nearly a fifth of UK universities’ total income in 2020/21, according to the Home Office. Despite this, Britain’s government has been accused of implementing anti-African policies in higher education. Late last year it launched a new program for postgraduate foreign students — High Potential Individual visa — but those with degrees from African universities are ineligible.

Alexis’s view

Britain’s attempts to curb the number of economic migrants entering the country will affect people across Africa — but Nigerians will be the big losers. With its large population, people from the West African country vastly outnumber other Africans pursuing higher education in Britain.

More young middle class Nigerians with the means to travel have for the last couple of decades left the country to pursue education and better work opportunities overseas. The UK, Canada and United States are typically the preferred destinations and many do return. But dwindling employment opportunities, runaway inflation, a crumbling higher education system and rising insecurity has sparked a large-scale exodus of young Nigerians in the last two years known locally as “Japa”. It’s a slang term meaning “flee” or “run” in the Yoruba language widely spoken in southwest Nigeria.

“We’re beginning to see that a lot of people just hide behind the studentship. So the student thing is not real, it’s not like they need the degrees,” Emdee Tiamiyu, a Nigerian influencer, told the BBC this week.

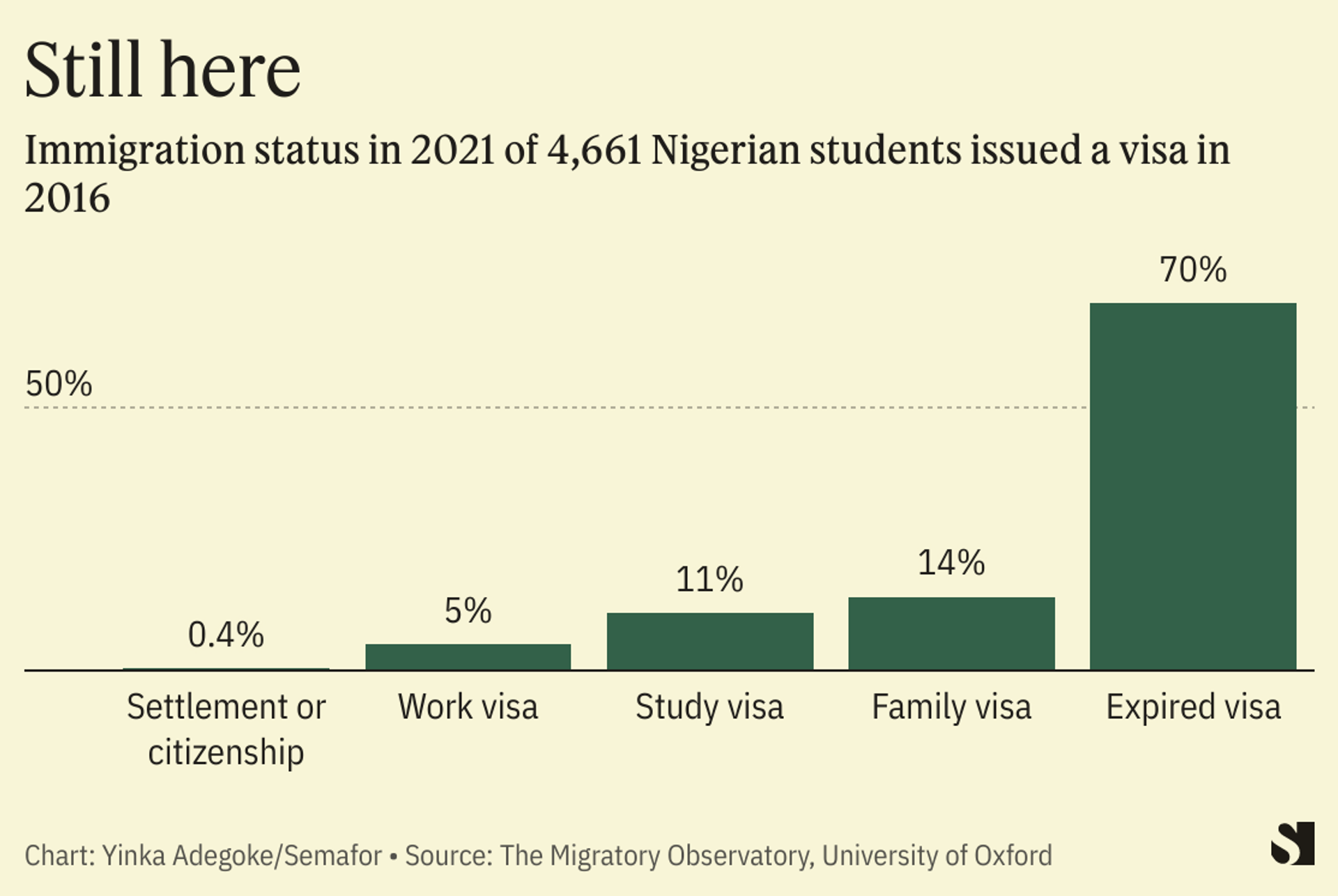

Tiamiyu apologized on his YouTube channel after a social media backlash in which he was accused of betraying Nigerians but the points he made ring true — for Nigerians who can afford it, studying in Britain and taking family offers a path out of Nigeria. Figures from Britain’s Home Office analyzed by Semafor Africa back up the trend. It shows that five years after graduation a larger proportion of Nigerians who arrived on a student visa remained in Britain on work visas.

But the era of using studies to migrate and take relatives is coming to an end.

Britain’s ruling Conservative party wants to reduce the number of foreigners who they argue take up housing and jobs, as well as putting a strain on the health system.

More attempts to cut immigration are likely in the run up to Britain’s next election. And, as the High Potential Visa showed, any initiatives to attract top talent to Britain are likely to exclude Africans.

None of this stop Nigerians pursuing a future overseas, it just means more will seek opportunities in the U.S. and Canada.

Room for Disagreement

Britain’s main opposition party, Labour, is ahead of the ruling Conservatives in opinion polls with a general election widely expected next year. Labour leader Keir Starmer has said he would not want to reduce the number of foreign students if his party was in government. “I want good students to come to the UK,” he said in a BBC interview on Monday. “I don’t think that’s the main issue,” he added, on the subject of foreign students who bring their dependents.

The View From Lagos

“It’s unfair that the UK wants to keep taking our money that fuels their economy but we can’t bring dependents because they don’t think we are productive yet,” said 25-year-old Oluwafemi Akinsanya, who’s studying integrated science and education at the University of Lagos. He said he has no desire to study in the UK because “whatever you do when you go to these countries, you’re going to be a second class citizen.”

Eucharia Ofonegbu, 32, wants to study in Britain some day — when she can afford it. But she says the policy would be an impediment if she were married, a view echoed by her classmate, Tola Olaitan. “It means I wouldn’t be able to take up an admission offer. I have a family and my children are still young,” said Olaitan, a 51-year-old postgraduate student of public and international affairs.

— Reporting by Alexander Onukwue in Lagos

Notable

- Data analyst Babajide Ogunsanwo gave an in-depth presentation of the numbers behind the Japa trend on Nigeria’s Channels TV.