The Facts

For decades, algae and seaweed were trumpeted as potentially revolutionary biofuels that would replace gasoline — only to suffer repeated setbacks and struggles to scale. But now a new generation of entrepreneurs is working to craft new climate solutions out of them.

In February, when ExxonMobil pulled the plug on a decade-long, $350 million research program to produce biofuels from algae, it felt like the final nail in the coffin for a prospective crude oil replacement that had been good for green marketing and not much else. But since then, other investors — including Chevron and the U.S. Department of Energy — have stepped up to finance new algae biofuel ventures, with a different focus: aviation fuels. And startups are now banking multimillion-dollar fundraising rounds to use algae and seaweed in other ways too — as a replacement for petroleum-based plastics and as a methane-cutting additive to cattle feed.

“Seaweed old hands are very averse to hype,” said Steven Hermans, an independent researcher and consultant in the seaweed and algae industry. “But it is a bit different this time, because there’s a lot more diversity in the things people are trying to do.”

Tim’s view

Algae and seaweed do have a lot of promise as a climate solution — just not as a replacement for gasoline.

The problem with Exxon’s biofuels program was that it was never able to deliver at a price point that could be competitive with gasoline, said Matthew Posewitz, a bioenergy researcher at Colorado School of Mines whose work was funded by Exxon for nearly a decade. The Exxon program made significant strides toward growing algae fast enough and with enough of the lipids needed to produce fuel, he said. But it started to feel like a futile exercise once it became clear that the solution to cutting cars’ carbon emissions was to electrify them, not use alternative fuels.

Exxon’s withdrawal was just the latest setback for the algae biofuels industry, which since the early 2000s has burned hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital with the promise of creating a low-carbon liquid fuel that, unlike corn-based ethanol, doesn’t compete for land with food crops. But algae is temperamental to grow, requires intensive breeding to produce high concentrations of lipids, and is cumbersome to harvest, leaving behind a string of bankrupt startups. A few things are different now, said Posewitz, which means the Exxon efforts haven’t gone entirely to waste.

For biofuels, the biggest target market has shifted to aviation fuel, which still looks promising because airplanes can’t be easily electrified. The California-based algae biofuels producer Viridos, after being ditched by Exxon, drew $25 million from Chevron, United Airlines, and the Bill Gates-backed firm Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and is aiming to produce commercial volumes of algae-based aviation fuel within two years. The U.S. Energy Department is also rolling out millions of dollars in grant funding for algae biofuels with a focus on aviation fuel.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act helped the sector by increasing tax credits for bio-based aviation fuels, with the aim of pushing U.S. production from about 15 million gallons per year today to 3 billion by 2030. Algae projects, which consume huge volumes of CO2, could also qualify for IRA carbon removal tax credits, and if used in the production of fertilizer or livestock feed would qualify for funding from a new $20 billion pool at the Department of Agriculture.

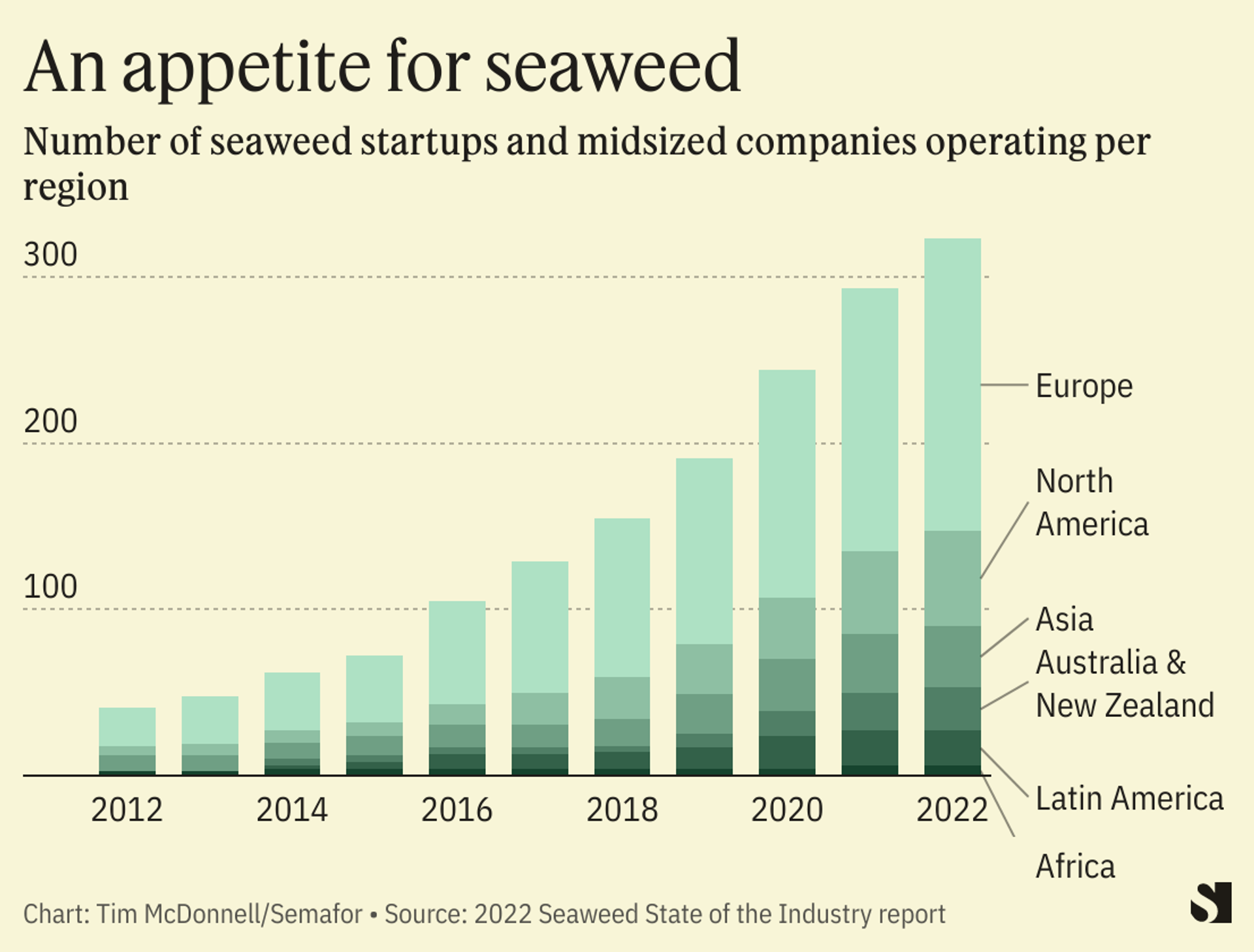

A growing number of startups are also looking beyond micro-algae grown in ponds to macro-algae, better known as kelp or seaweed, which can be used for bioplastics, fertilizers, livestock feed, and other applications. Since 2020, seaweed and algae startups have raised nearly half a billion dollars, according to Hermans’ database. The appeal is that kelp can be raised in huge volumes directly in the ocean, where real estate is limitless and the required nutrients are free.

“Algae and seaweed are like a mind virus,” said Alex Brown, CEO of Alga Biosciences, which produces a seaweed-based, methane-reducing additive for cattle feed. “Once you start thinking about them from a climate perspective, it’s hard not to get obsessed.”

Room for Disagreement

Micro-algae and seaweed have numerous technical hurdles still to overcome, and the industry as a whole is in a chicken-and-egg dilemma: There’s insufficient investment in production and processing because the market demand is unproven, but without that investment algae products will struggle to compete on price with petroleum products. “If you don’t work the kinks out early, the money will go away quickly,” Posewitz warned.

The View From Australia

Livestock methane reduction is one of the most promising new applications for seaweed. FutureFeed, a Brisbane-based startup, patented a method for mixing cattle feed with just a few grams of a seaweed variety called Asparagopsis, per kilo of feed, producing a chemical reaction in cows that almost completely eliminates methane-laden farts and burps, and causes the cows to gain weight more efficiently. Although the feed is more expensive than normal feed, CEO Alex Baker said farmers could sell carbon credits based on their cows to offset the expense, noting that meat retailers are increasingly willing to pay a premium for low-emissions products.

Notable

- Seaweed cultivation in the U.S. faces an obstacle renewables developers know well: Permitting reform. According to Hermans, the time to receive a permit for offshore kelp-cultivation in California has doubled since 2018, to nearly seven years.