The News

The nascent market for carbon removal credits — a more expensive, but far more credible alternative to increasingly discredited carbon offsets — took a few leaps forward this month, with an unprecedented round of corporate purchase agreements that push fringe technologies closer to the mainstream of climate action.

In the last two weeks, Microsoft, JPMorgan Chase, Boeing, and a purchasing collective called Frontier — that represents tech giants including Stripe, Alphabet, and Meta — all agreed to buy large volumes of carbon removal credits, aiming to kick-start a virtuous cycle of demand and supply.

Tim’s view

The carbon removal industry is at a turning point: Technologies are maturing and companies in the U.S. are beginning to tap the juicy carbon-removal tax incentives offered by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Carbon removal credits differ from traditional carbon offsets as they give the purchaser credit for existing CO2 emissions that are permanently withdrawn from the atmosphere or ocean, rather than for new emissions that are avoided. While companies work to reduce their operational and supply-chain carbon footprints, carbon removal credits offer a way to make progress toward net zero that is generally seen as more scientifically credible — albeit much more expensive — than offsets.

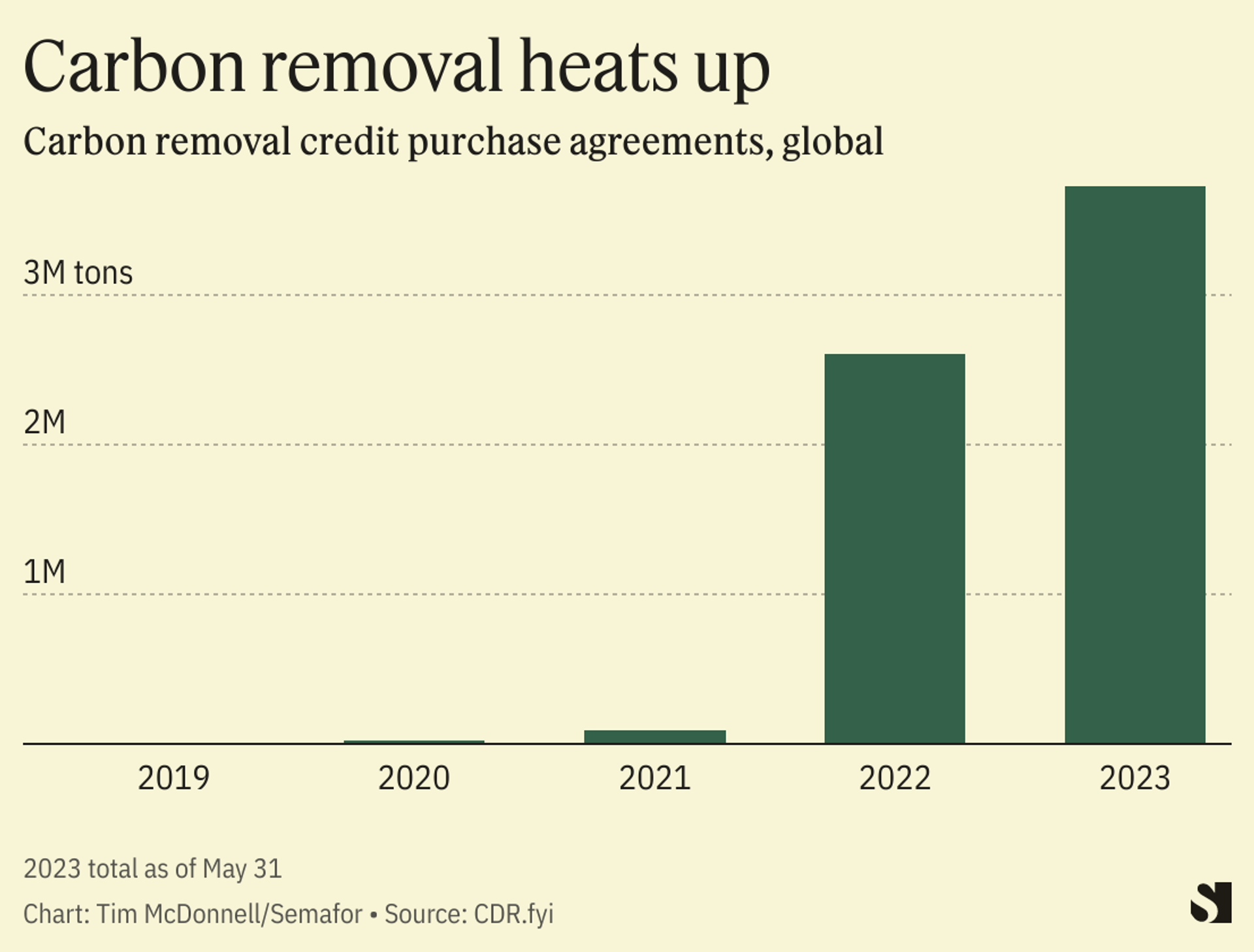

Today the market for carbon removal is tiny: Last year, 4,000 times more tons of carbon offsets were sold than carbon removals. The technologies — which include direct atmosphere capture with big fans, converting farm waste to oil that gets injected deep underground, and spreading carbon-sucking crushed rocks on farmland, among others — are at about the stage solar energy was two decades ago, with few customers and no economies of scale.

For now, the most important missing piece is customers willing to pay hundreds of dollars per ton to counteract their emissions. But they’re beginning to emerge. Together the commitments made by Boeing, Frontier, Microsoft, and JPMorgan are about a million tons more than were sold globally in 2022.

For these buyers, getting in early on carbon removal allows them to offset emissions in a way that is less likely than traditional offsets to draw accusations of greenwashing (or even lawsuits, as Delta Airlines discovered this week). It also allows them to jump to the front of the line for a product where demand is likely to far outpace supply for the foreseeable future.

The View From Frontier

Frontier’s deal — $53 million to buy 112,000 tons between 2024 and 2030 — is its first offtake agreement. The group was formed last year to solve a chicken-and-egg problem, said Nan Ransohoff, who leads the group and is head of climate at Stripe.

“The underlying goal is to send a loud demand signal to entrepreneurs, scientists, and researchers that there is a market for carbon removal,” she said. “Founders don’t want to start companies if there’s going to be no revenue stream, and investors don’t want to invest. So we essentially created a synthetic market to pull companies into existence.”

The supplier of removal credits will be San Francisco-based Charm Industrial, a startup that converts farm waste into an oil that gets injected deep underground (thereby sequestering the atmospheric carbon the plants consumed while growing). In the three years since it was founded, the company has only delivered about 6,000 tons of removals, so the Frontier deal is a huge test of its ability to expand. But Ransohoff said she thinks Charm is ready. The key question is whether a few big, high-dollar purchase orders — the Frontier deal works out to about $470 per ton, while traditional carbon offsets range from about $1-$50 — can give Charm the scale it needs to drop its price dramatically.

Room for Disagreement

Until the price of carbon removal credits falls below $100 per ton, the market will be limited to a small number of deep-pocketed, image-conscious corporate buyers. Even then, Ransohoff said, the scale of carbon removal called for by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — at least five billion tons per year by 2050 — won’t be possible without much more government support. To put that figure in context, purchase commitments only totaled 2.6 million tons last year, of which only about 2% have actually been delivered.

In its early days, solar energy was propelled by the fortunate alignment of policy and tax incentives in the U.S., China, and Europe that allowed buyers and sellers to develop together, said Julio Friedmann, chief scientist at the consulting firm Carbon Direct. “We don’t have the same policy alignment for carbon removal,” he said, so the chicken-and-egg problem persists: “Deep cost reductions are entirely a function of how quickly we deploy.”

Notable

- Not everyone agrees that carbon removal credits should be counted against corporate carbon footprints. There’s a dispute brewing between the industry and United Nations bureaucrats, Axios reported, on whether removals should be included in the global carbon trading system that is mandated by the Paris Agreement but is still under development.