The News

If it were just about the money, the US would be on track to build the battery industry it needs to power its clean tech revolution. Sadly for the country, it’s not just about money.

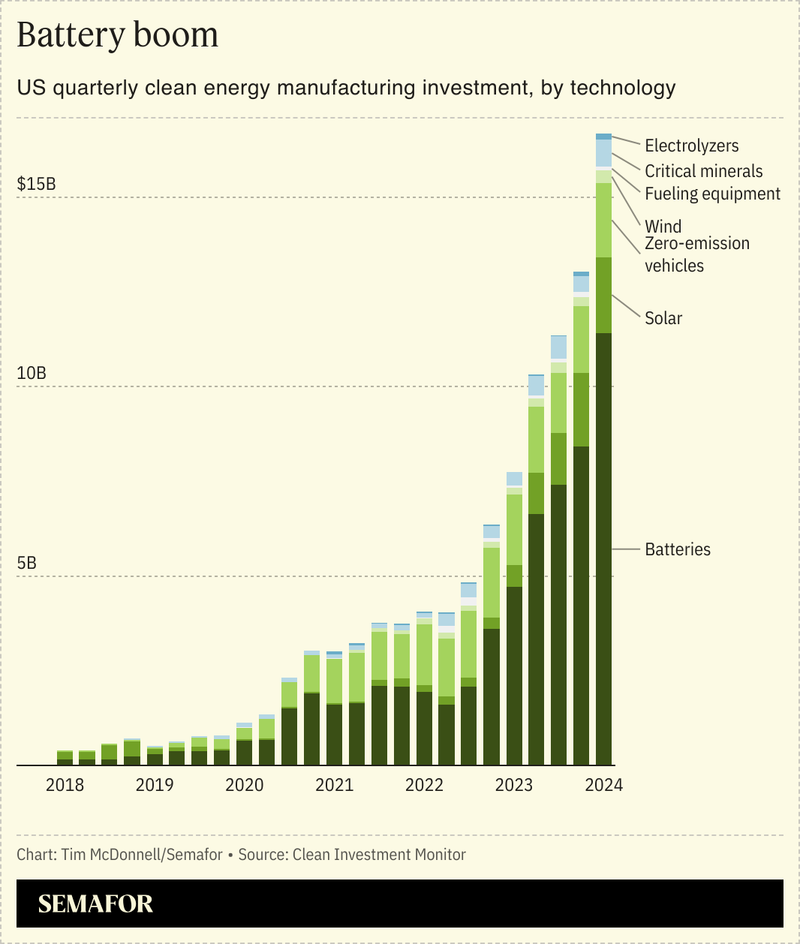

A new report from the Rhodium Group think tank this week showed that funds are pouring into battery factories as automakers and other major battery customers look to take advantage of tax bonuses for domestic content. In the first quarter of this year, battery manufacturing investment reached a record $11.4 billion, more than double the total investment in other cleantech sectors combined.

If all of the new battery factories are completed on schedule, their production capacity will exceed projected US demand, marking a fundamental shift in the cleantech trade imbalance that the Biden administration is scrambling to correct. If only it were that simple.

In this article:

Tim’s view

A bigger supply of batteries is foundational to US climate aspirations. It will help drive electric vehicle adoption, and balance the intermittent production of some renewables technologies for the wider power grid — but an array of vexing, interlocked problems, both domestic and international, could hold the US back from building the battery system it needs.

One problem is China. Its companies dominate the battery industry, and are a decade or more ahead of their American competitors. Chinese companies’ battery production costs are so low, and their products so advanced, that new tariffs announced this month — up to 25% from 7.5% — aren’t high enough to really make a difference, some battery executives say. The tariffs, which phase up over several years, are a bet by the Biden administration that US manufacturers can scale up quickly enough without causing price spikes or supply delays for the EV drivers, utilities, and renewable energy project developers who are the main end customers for batteries.

But Mukesh Chatter, CEO of the Massachusetts battery startup Alsym Energy, said in an interview that typical imported lithium-ion batteries sell for about $40 per kilowatt-hour. US manufacturers, meanwhile, can spend that much just on their material costs. If the new tariffs tack another $10 on the import price, “how that helps anybody is not clear to me,” he said. “If somebody is going to drown, it doesn’t make a difference whether they drown in 10 feet of water or 100 feet.”

Another problem, Chatter said, is that federal funding for basic research and commercialization of new battery technologies, although theoretically plentiful thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, remains painfully slow and cumbersome to access. Chatter, whose company uses a non-lithium-based technology, also complained of what he perceives as a systemic funding bias in favor of lithium. That risks the US ceding its advantage in the one area — basic tech innovation — where it has always had an edge over China. “Eventually this is going to come down to IP,” he said. “If that’s lost, nothing else matters.”

A third problem is more pragmatic. The same electricity grid bottlenecks that have emerged as the chief obstacle to the buildout of renewable energy also make it difficult and expensive to build an energy-intensive factory. Chatter is desperate to upgrade the power capacity of his factory (“right now, we have to shut one thing off to turn another thing on”) but has been told by his utility that the wait time will be at least a year, due to equipment shortages and bureaucratic issues.

Permitting issues also impede the actual installation of grid-scale batteries once they’re produced, said Mike Hall, CEO of Anza, which provides data to renewables project developers: “Permits and interconnection are bigger issues than market or policy issues at this point.” US battery companies have also alternately faced severe labor shortages, and had to make deep layoffs when profits don’t materialize on time.

The overweening focus on trade protectionism is short-sighted, Chatter said. “We don’t need handouts. We just need the removal of impediments. If we lose the battle for batteries, we’re losing out on millions of future jobs.”

Room for Disagreement

Rather than just wait for domestic manufacturing to catch up, US commercial battery buyers need to seek out more creative ways around the China tariffs, said Lynlee Brown, who advises companies on global trade issues for the consulting firm Ernst & Young. That could mean forging new deals with suppliers in Japan and South Korea, as many are already doing. And to the extent that Chinese suppliers are unavoidable, clean tech can take a cue from the apparel and computer hardware industries and do anything it can to reduce the stated value of imports, from which the tariff is calculated.

It might be cheaper, for example, for a company to increase its R&D budget and develop its own methods for assembling unfinished products from China, rather than paying a Chinese company for the IP premium embedded in finished products, Brown said. Or it might mean sourcing all but the most crucial bits of a certain product from China, in order to make a case to customs officials that the product isn’t “essentially” Chinese. These workarounds are commonplace in many globally traded products, Brown said. But they will be more challenging in the much smaller, newer, and more specialized area of cleantech.

Notable

- One US battery startup brought its technology from lab to commercialization in record time, Bloomberg reported, by turning to an unusual key ingredient: Rust.