The News

The climate change-driven home insurance crisis in the U.S. is accelerating.

This week, Allstate announced it will no longer write new home insurance policies in California, saying that the risk of wildfires has grown out of proportion with the premiums the company is able to charge. State Farm made a similar move last week, following AIG last year. Insurers are also bailing on other vulnerable states: Most in Florida and Louisiana have either left or gone bankrupt. And where insurance is still available, prices are skyrocketing: Since 2015, average rates in Florida have spiked 57%, compared to a national average increase of 21%.

Tim’s view

The flight of insurers from markets with high exposure to climate catastrophes isn’t an inevitable outcome of rising risk. Instead, it’s a symptom of a regulatory environment in which policymakers have chosen to prioritize short-term protections for a small subset of consumers over the longer-term interests of all homeowners.

Insurance premiums in risky areas need to increase. When they are kept artificially low, all homeowners ultimately pay the price. But in California, insurers have limited discretion in setting rates that are commensurate with rising risk. State rules require insurers to seek prior approval from regulators for rate hikes. Insurers are prohibited from pegging their rates to their own reinsurance expenses, which are also rising because of wildfire risk. And they are required to assess wildfire risk by looking backward at the record of losses over the preceding 20 years, which is not useful in the context of climate change.

“Current state rules punish the very behavior that everyone wants, which is for insurers to voluntarily go into high risk areas,” said Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, a trade group. “An insurer gets no credit for writing in new, higher-risk areas because they need to first experience big losses in order to get approval to charge the higher rates to support the higher losses they expect in riskier areas. Not a good business decision.”

The moves by Allstate and State Farm are essentially a negotiating tactic with regulators to change these rules, said Benjamin Keys, a real estate economist at the University of Pennsylvania. On Wednesday, California scheduled a public workshop to discuss ways to achieve “fair and justified pricing of insurance” that accounts for increased risk while protecting against price gouging. But Frazier warned that insurance regulations require a supermajority of state legislators to amend, a high bar when it requires politicians to essentially endorse higher insurance rates.

That challenge, and the conflicting consumer protection imperatives lawmakers face, is well illustrated by a lawsuit filed last week by the attorneys general of Florida and nine other flood-prone states against the federal government for raising the cost of federal flood insurance — even though that program is more than $20 billion in debt. That lawsuit, Keys said, is “profoundly counterproductive.”

Know More

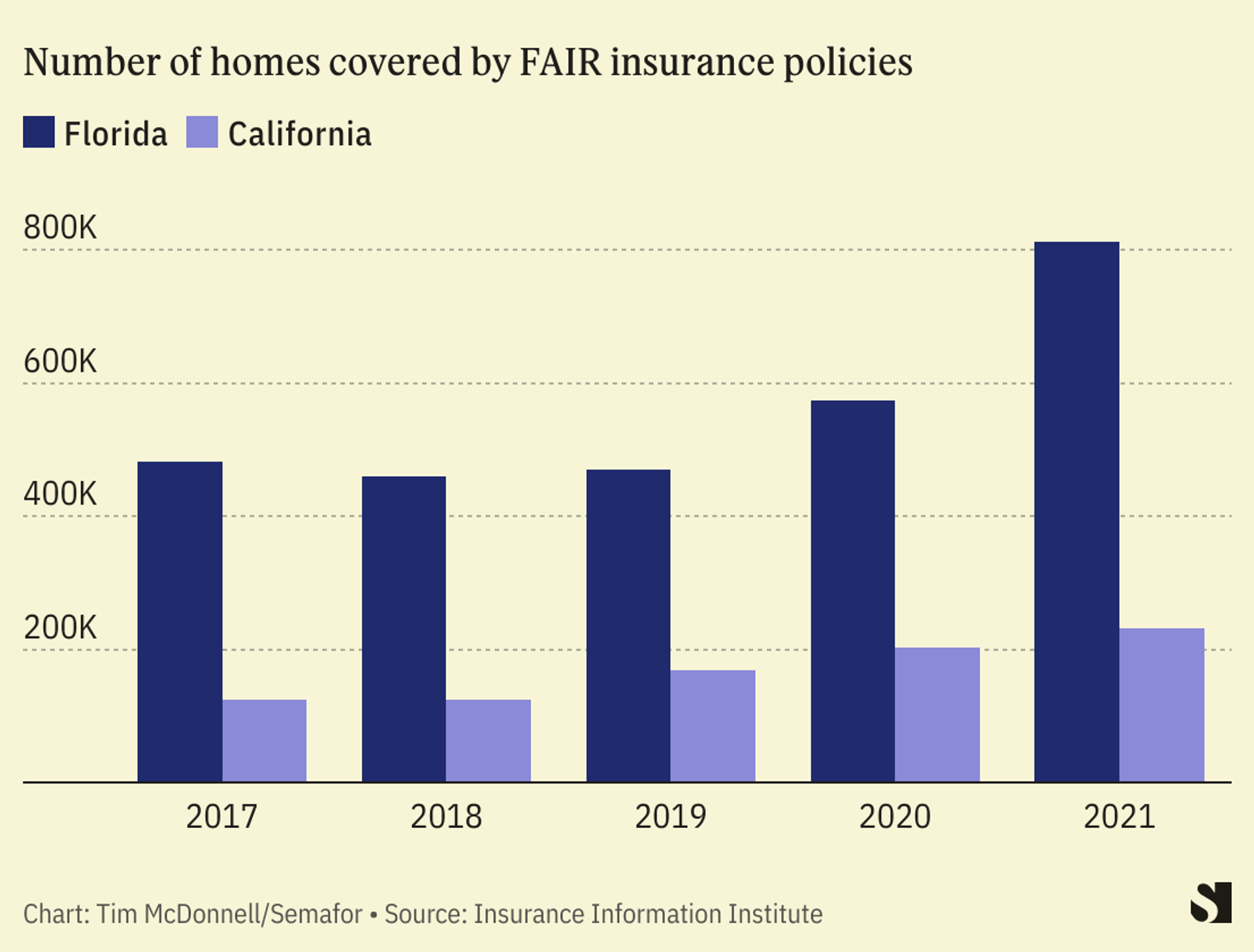

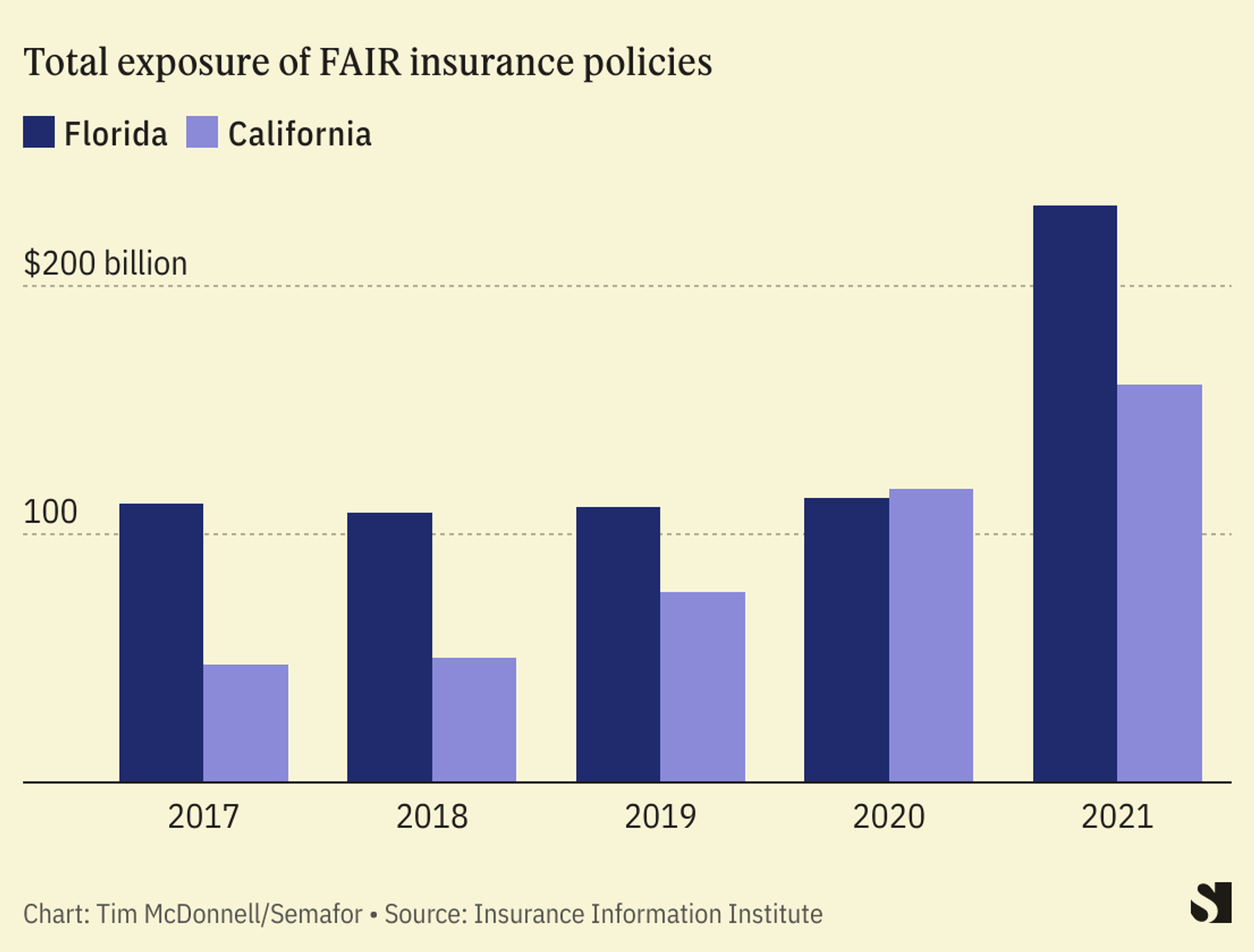

When private insurance is not available, most states, including California, offer so-called Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans, also known as “last resort” plans, that are overseen by the state but financed by a pool of private insurers. Participation in these plans is skyrocketing nationally; since 2017, the combined value of homes covered by these plans has jumped 70%, to more than $500 billion.

There are a few problems with this trend. For homeowners, FAIR plans tend to be more expensive and offer less comprehensive coverage than regular private coverage. Given the rush of participants, they are likely undercapitalized, Keys said, and may not be able to pay out in the event of a big disaster. Yet because they are tightly regulated, they are even more subject to political capture than the private market, and thus may be less willing or able to raise rates to a level commensurate with risk. And because a private insurers’ required contribution to the FAIR pool is determined by its share of the private market, every time one insurer leaves a state, all the others are on the hook for more FAIR coverage, creating an incentive to be first out the door.

“The FAIR plans were never designed to operate at this type of scale,” Keys said. “It’s fundamentally not sustainable.”

The View From South Carolina

One way to place more of the costs of owning a home in a risky place onto the homeowner is to cut off their access to public insurance. A bill now under consideration in the Senate, sponsored by Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and Tom Carper (D-Del.) would expand areas in South Carolina and other stretches of the East Coast that are designated as ecologically sensitive and subject to elevated flood risk. Homes in those areas are not eligible for federal flood insurance or infrastructure funding. A spokesperson for Graham said that the bill is not specifically intended to discourage development in risky areas, but would limit taxpayers’ exposure to risky choices made by individual homeowners.

Room for Disagreement

The problem with allowing rates to rise precipitously or with cutting off public insurance is that such changes are likely to fall most heavily on low-income households. There’s a misperception that homes in fire-prone forests or along beaches are mostly vacation properties for the wealthy, said Margaret Walls, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future, a research nonprofit. In fact, homes in high-risk areas, precisely because they are high risk, have historically been less expensive, and therefore drawn lower-income buyers. Now, low-income zip codes may be more likely to have their policies canceled because of wildfire risk, Walls found. A separate RFF study in February also found that accurate pricing of flood risk would lower the value of homes owned by low-income families nationwide by up to 10%.

In some cases, government buyouts of high-risk properties may be a solution – in the last 40 years federal funds have been used to purchase about 48,000 flood-exposed properties nationwide. But that approach hasn’t been tested in wildfire zones, and would also be massively expensive to scale. Federal or state governments could also pair insurance subsidies for low-income households with financial aid for home improvements to mitigate damage from floods or fires.

Notable

- Climate risk should also be priced into federally-backed mortgages, Keys argued in a recent New York Times column. Higher interest rates for higher risk would discourage construction in vulnerable areas.

- Another way to lower wildfire risk for insurers: Lower the risk of catastrophic wildfires. In a new edition of Semafor’s Agenda video series, science journalist Adam Cole explains how the government needs to change its approach to firefighting.