The News

WEST PALM BEACH, Florida — The road to understanding Donald Trump’s appeal to a segment of Black America — and his hopes of winning back the presidency by pulling a few precious votes away from Democrats — runs through Trump’s Black friends, a loose set of iconic sports figures from the 1980s.

That, at least, was the impression I got from his campaign when I set out to interview Trump about his apparent gains with Black men, a group of voters who some public polls show are more likely to consider backing him this year. Trump’s aides wouldn’t promise a meeting with the former president just yet — instead, they started setting up interviews with older athletes who are supporting his campaign.

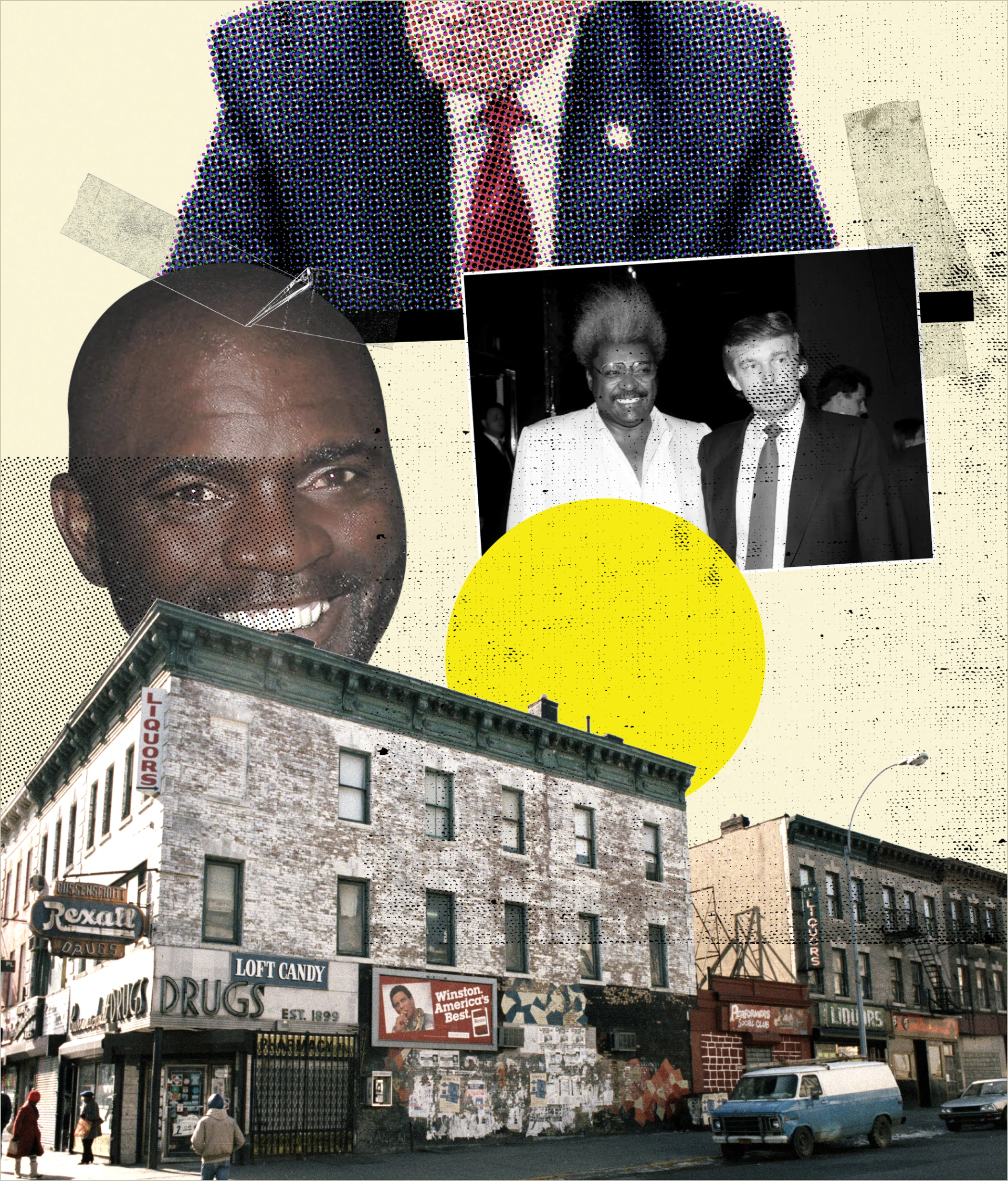

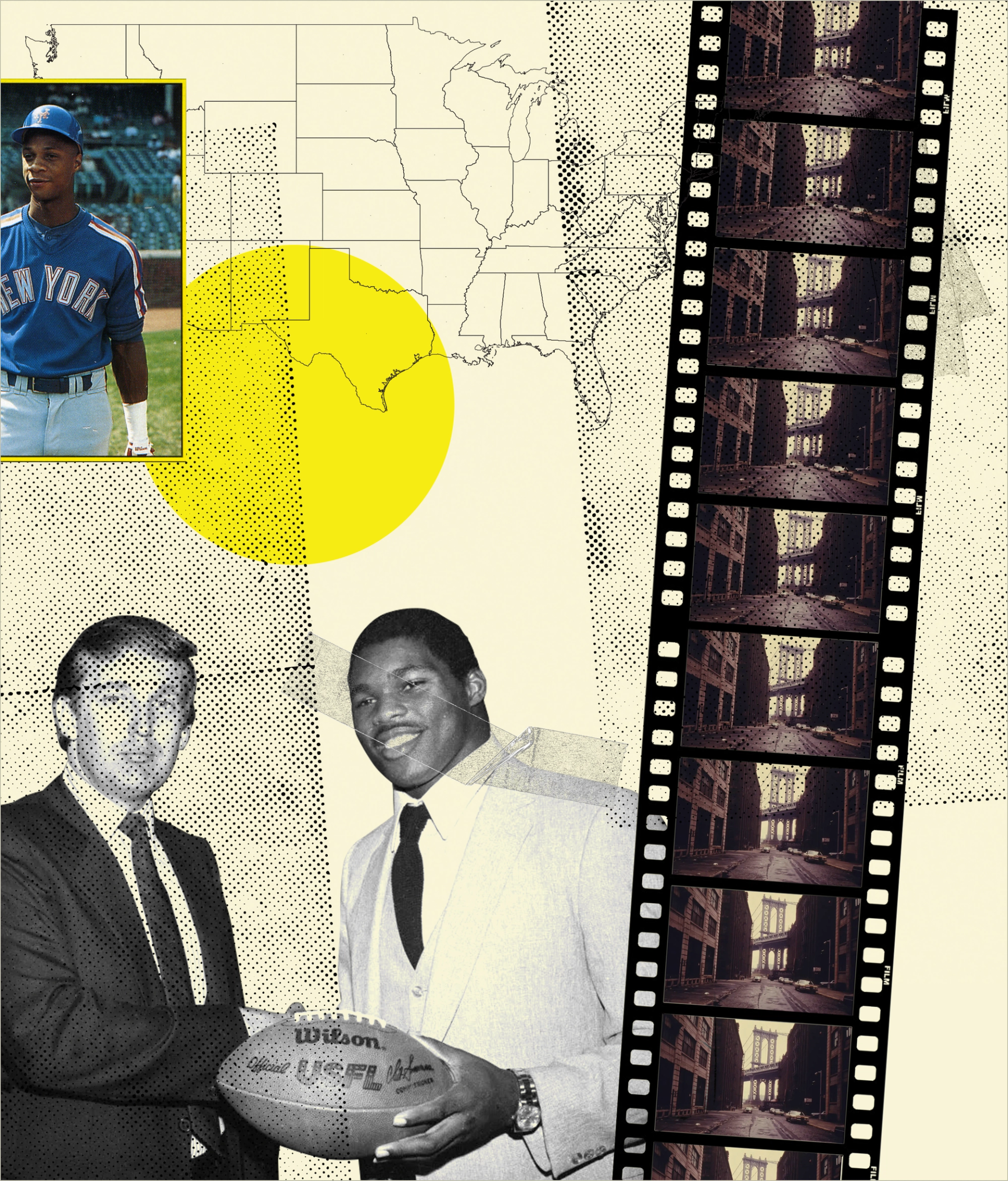

Not long after, I got a call from Mets and Yankees slugger Darryl Strawberry. That was the beginning of an odyssey through the heroes and villains of my childhood: Over the next few weeks, I chatted with heavyweight champion Mike Tyson, stood backstage at a Trump rally with retired NFL star Lawrence Taylor, and traveled to meet boxing promoter Don King in person. Eventually, I talked to Trump himself.

These men, now aged 57 to 92, would make unlikely spokespeople for almost any other candidate and they mostly aren’t known for their politics. But they do have a lot in common with Trump. They were household names at the same time as Trump’s New York heyday. They were frequently in the tabloids, often for the wrong reasons, and it took a push from the campaign to persuade some of them to talk to a strange reporter. Nearly all of them had faced serious legal issues, including several criminal convictions.

I met Trump six days after his own felony conviction, in the “Great Room” at Mar-a-Lago. He had just finished a sit-down with Dr. Phil. I asked him, among other things, what I should take away from his warm relationship with the Black men who had been singing his praises to me.

“They see what I’ve done and they see strength, they want strength, okay,” he said. “They want strength, they want security. They want jobs, they want to have their jobs. They don’t want to have millions of people come and take their jobs. And we — that’s what’s happening. These people that are coming into our country are taking jobs away from African Americans and they know it.”

I reminded him I was talking about millionaires, not working stiffs worried about immigrant labor. He conceded, jokingly, that Don King was not at risk of being replaced.

Their relationships came up more directly after my next question, when I asked how he responds to Black voters who call him racist.

“I have so many Black friends that if I were a racist, they wouldn’t be friends, they would know better than anybody, and fast,” he told me. “They would not be with me for two minutes if they thought I was racist — and I’m not racist!”

We’ll find out in November if Trump wins this argument. He lost Black voters by a 92-8 margin in his last election, according to a Pew Research study, despite high hopes for a breakthrough that cycle. In 2016, he settled for boasting that fewer Black voters had showed up to the polls that year, which he said was “almost as good” as their support.

But while he hasn’t succeeded yet, Trump was getting at something noteworthy in our conversation. A common obstacle to outreach for Republican politicians is that they’re often from cloistered, white spaces where they don’t have many interactions with Black people. That’s not Trump’s issue: He’s had famous “Black friends,” as they say, throughout his career, even as he was constantly dogged by accusations of racism at the same time. The people I spoke to weren’t passing acquaintances, either. They had made deals together, weathered crises together, and shared family gatherings together. One had even chaperoned Don Jr. on a trip to Disney World.

And while a handful of aging Reagan-era celebrities obviously aren’t a stand-in for all Black people, and especially the rank-and-file voters who actually decide elections, they do represent a recognizable part of Black culture that Trump has long been plugged into. His success in the election may partly depend on whether, in this shifting cultural moment, there are enough Americans thinking about the election the way Mike Tyson does.

‘I’m Still Here’

Trump’s aides seemed to think I might understand their candidate because I was shaped by the same New York era. I grew up in Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s at the nexus of these two Black Americas, where ordinary folks and celebrities meet. When I was in my early twenties, I worked at Dooney & Bourke in Trump Tower, selling leather handbags to tourists. I knew Tyson as a global icon, but also as the local bigshot who ran in the same circles as my childhood friends’ older siblings.

And so a couple of weeks after I pitched the campaign an interview, I was in Wildwood, New Jersey talking to Taylor and his old Giants teammate Ottis “OJ” Anderson at a Trump rally. Taylor’s case for Trump was one I’d heard from voters many, many times before.

“He’s going to speak his mind,” he told me. “He doesn’t care how it comes out.”

He added, crucially: “He’s a man’s man.”

Taylor, like all of the names I had been put in touch with, had a business relationship with Trump at some point as well as a social one. He recalled meeting Trump when he tried to poach him as part of a failed football venture that briefly competed with the NFL. “He put a million dollars in my account and said, listen, he wants me to play — and we’ve been friends ever since,” he said.

At the time of that rally, Trump was still on trial in a Manhattan court over hush money payments to an adult film actress ahead of his first election; he faces three more pending criminal trials in state and federal courts. It was a problem his friends could relate to.

Taylor, who was plagued by off-field issues throughout his Hall-of-Fame playing career, pleaded guilty in 2011 to patronizing a 16-year-old prostitute. (He said he believed she was 19). Trump stood by Tyson in the 1990s while he was jailed on a rape charge that he denied (he also was hosting his fights, which required the boxer to be out of jail). In 2016, the then-chairman of the Republican National Committee, Reince Priebus reportedly intervened to keep King off the 2016 convention stage because of his prior manslaughter conviction.

“The party could not associate itself with someone convicted of a felony,” the New York Times noted at the time, which might as well have been a thousand years ago.

Strawberry came out the other side of drug addiction and jail to become an evangelical preacher. When I spoke to him, he mentioned that he and other sports stars know what it’s like to face the burning gaze of the public, something he connected to support for Trump.

“People are hoping that he comes back, a lot of athletes,” Strawberry said. “A lot of times people are afraid to say — they’re afraid of public opinion, and I’ve had public opinion my whole life…they were saying I couldn’t survive, I couldn’t make it. And guess what? I’m still here.”

Trump’s gains with nonwhite voters in the polls have mostly come from younger Americans. When I mentioned to Trump during our interview that the people that I’d been directed to talk to all seemed to be associated with a certain bygone period, he immediately thought to add another name to the list.

“Did you give her Herschel?” he asked his staff.

He was referring to Herschel Walker, the former football star who lost his Senate race last cycle while facing political attacks over allegations of past domestic abuse and previously unacknowledged children. A born-again Christian, Walker told voters at the time that he had moved past a dark period of mental illness and was reformed.

A few days later, I received a call from Walker, who adores Trump. He recalled how they became close in the 1980s, when he was also involved in Trump’s football endeavors. Walker volunteered to take a young Don Jr. to Disney World with his own family while his team was at training camp in Orlando. The ease with which a white New York businessman befriended “a Black kid who came from this little town with absolutely nothing,” made a strong impression.

“I know the man has got a great heart,” he said.

Walker rejected the premise that Trump had a problem with Black voters — he said he was sick of being asked to “defend” him as a Black man, as if supporting Trump required an extraordinary explanation. His advice to the campaign was to start showing up more often in Black neighborhoods and to treat voters the same as they would white voters.

“What I told Don is I think you need to go see more Black people in the cities and talk to them,” he said. “I said, you know, they love you.”

‘They See What’s Happening’

There’s a reason I keep mentioning the shared legal problems of Trump and his friends: It’s become inextricable from any discussion of his outreach to Black voters.

Before his Manhattan trial, Trump had taken to comparing his personal legal struggles to those Black men face in the criminal justice system. At one point in February, he boasted that “the Black population” loved seeing his mugshot in Fulton County, Georgia where he faces separate criminal charges over election interference. He has repeatedly compared himself to Nelson Mandela, the late South African president who spent decades as a political prisoner while opposing apartheid.

Democrats have accused him of reinforcing ugly stereotypes for his personal benefit. When I asked him about the topic, he said it wouldn’t be part of his pitch to Black voters — but also couldn’t help making the comparison again.

“No, it won’t be part of my message,” Trump said. “I think it’s through osmosis. They see what’s happening. And a lot of them feel that similar things have happened to them. I mean, they’ve expressed that to me very plainly and very clear. They see what’s happened to them.”

Black conservatives aren’t always happy about this kind of talk either. Michaelah Montgomery, a conservative activist, said she broached the topic with Trump at a dinner he hosted with HBCU students on the night of our interview. “Don’t put that out there that Black people like you because you’re a felon,” she told me she said to Trump. “The Black people don’t like you because you’re a felon. The Black people who like you like you because they feel like you’re experiencing the things that they have been complaining about for years, and now maybe you can shine a light on the cries that have been falling on deaf ears for all of this time.”

It might make some people cringe, but it’s easier to understand where Trump gets the impression this is a relatable message when you’re spending time with his famous friends.

“If I never saw Donald Trump and didn’t know he was white, I would think that he was Black,” Tyson told me. “The way they were treating him in the papers and in the press? Think about that, the way they treat him in court? That’s the way they did Black people.”

King once said Trump understood Black people because “no matter what you say or do, you are guilty as hell.” The same week we spoke, rapper 50 Cent said during a Capitol visit that Black men identify with Trump “because they got RICO charges,” a reference to the statute being used to prosecute Trump in Georgia.

“Look at what happened to a lot of the people of color and right now the injustice that is happening with Donald,” Walker told me. “Right now, it’s almost just — it’s almost similar to that.”

Of course, the question looming over this and every prior Trump campaign has been whether a few wealthy entertainers and athletes are representative of voters writ large. That’s especially true when they’ve faced their own accusations in the public eye that might make them uniquely inclined towards defending Trump.

There’s at least some early evidence Trump has misread the room in this regard: A poll by Democratic firm Navigator Research found Black voters were the group most likely to think Trump was guilty in the Manhattan case, by a 76-15 margin. The New York Times’ Nate Cohn also noted that their own post-verdict polling showed President Biden shoring up support with younger, politically disengaged, nonwhite voters — the exact group Trump is targeting.

The View From Democrats

Democrats have watched Trump’s polling rise with a mix of shock, anger, and disbelief. He has a long history of remarks that were widely condemned as racist and feuded as president with Black lawmakers like civil rights icon John Lewis, whose district he blasted as “crime-infested” and who he continued to grouse about after his death. Who, they ask, is buying this?

“He’s trying to lean into his identity, Donald Trump’s identity, as a criminal, because he’s now a convicted felon,” Rep. Steven Horsford, the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, told me. “It’s not a policy agenda that improves the lives of anyone, much less Black Americans. And not only is it an insult, it is an affront to Black men and Black people and what it is we are fighting for”

Horsford, who has been holding a tour of Black barbershops in his Las Vegas-area district, described Trump’s campaign as “a bunch of platitudes with no actual policy or commitment behind them.”

The Biden campaign has taken Trump’s polling gains seriously, though. In high-profile campaign speeches, ads, and statements, they’ve tried to remind voters — and especially younger voters — of his history of inflammatory statements and accusations of discrimination.

“Donald Trump has spent his life and political career disrespecting Black men every chance he gets: he entered public life by falsely accusing five black men of murder, denigrated George Floyd’s memory, and launched his political career trying to undermine the first Black president as the architect of birtherism,” Senior Biden Spokesperson Sarafina Chitikatold Semafor.

Voters in their twenties today were children when Trump was leading his false birther charge against Barack Obama, a lengthy public crusade to prove that the first Black president was secretly born in Kenya and that his Ivy League pedigree at Columbia and Harvard Law School was nothing more than affirmative action. He dropped the issue just weeks before the 2016 election.

I brought the topic up with Trump in passing; he responded only in generalities about his broader record on issues like HBCU funding. But even some of his friends were stung by that one. Tyson told me he “didn’t agree” with Trump’s Obama-bashing at the time, though he added he didn’t let it affect their relationship. Walker chalked it up as “part of this politics thing.”

Democrats are also hoping to capture the energy of four years ago, when the nation was engaged in large-scale protests against police brutality and racial inequality, a movement that notably also had broad buy-in from Black athletes in the major sports leagues. Trump condemned the Black Lives Matter movement in his debates with Biden and staged a photo-op outside the White House after riot police tear-gassed Lafayette Square. More recently, he bragged in a Time interview about how he had threatened protestors who “desecrated” monuments with 10-year minimum sentences.

Then there’s the “Central Park Five,” a group of teenagers who were arrested in 1989 and charged with the rape of a jogger, prompting Trump to take out an ad calling to reinstate the death penalty. They were later exonerated — one recently became a New York City Council member — but Trump has never acknowledged their innocence. Their story is featured in Biden’s campaign ads.

When I spoke to Tyson, he said the topic still comes up when he tries to sell fellow celebrities on Trump.

“The only thing they can say is that he’s a racist,” he said. “Central Park Five, other than that, they can’t bring up anything else. And most of those famous Black people, they weren’t saying that when he was getting them free tickets at the fight and getting them free rooms at the fight — they weren’t saying he was a racist then.”

That Trump is generous to his friends is part of the Democrats’ message, too. They’re arguing the former president’s sudden interest in discrimination as a smokescreen: It’s not that he wants a more just legal system, it’s that he wants to abuse the law in order to protect himself, reward his allies, and punish his enemies.

“What do you think would have happened if Black Americans had stormed the Capitol?” Biden said at a Philadelphia event aimed at Black voters in May. “I don’t think he’d be talking about pardons.”

First Step

Trump has made tough talk on crime central to his campaign. But he also appealed to Black voters in 2020 by touting his work on the First Step Act, the most significant criminal justice reform package in years, and he boasted about granting clemency and pardons to some nonviolent drug offenders.

The politics of that movement have changed significantly since then. Following a crime surge in his final year in office, Trump began talking less about freeing prisoners on old drug charges, and more about executing drug dealers. A number of Trump’s Republican primary challengers criticized the First Step Act and even suggested repealing it.

So I was at least somewhat surprised to hear Trump still sounded largely like it was 2020 when I raised these topics.

“People have been treated very unfairly and it’s largely Black people,” he said. “It’s Hispanic people, it’s not just Black.”

In fact, he talked about expanding the First Step Act — though it’s not clear how, and Trump has a history of promising policy rollouts that are always right around the corner.

“We’re going to be doing extensions of that,” he told me, adding that he’d release amendments for “strengthening certain things” while “working on fairness.”

In some corners of the right, like Tucker Carlson’s online show, there’s been a renewed effort to defend Derek Chauvin, the Minnesota cop who killed George Floyd and is currently in jail for murder. Trump has pledged to “indemnify all police officers and law enforcement officials” if he’s re-elected, touching on a longstanding debate about whether police officers should be held personally responsible for their professional actions.

He has not elaborated on how broadly this policy should be applied, nor is it clear he has much ability to influence these cases at all. But he did tell me he believed Chauvin should not have been shielded from prosecution.

“No. What he did was out of bounds. He was out of bounds. That was crazy. When I looked at that — I watched that tape many times, no,” he said. “But they have a lot of people that did a good job, and they were innocent. And you know, they’ve lost everything. They’ve lost everything.”

Fight Night

“Say hello to Don — I love Don King,” Trump told me before we parted. “He’s unbelievable. This guy was unique. There was never anybody like Don King.”

And so after my visit to Mar-a-Lago, my nostalgia tour took me 45 miles south to Hollywood, Florida, where King was promoting his Fist of Fury boxing event.

When I arrived for the weigh-in, King, 92 years old, was slumped in a wheelchair, though still strikingly tall. The light wasn’t in his eyes like it used to be, but he could still pull off a look — he was wearing one of his signature rhinestone denim jackets with an American flag design that he’s been photographed in many times before. With the assistance of his two grandsons, he was able to get on stage and stand just long enough to pose between boxers during their staredowns.

King wasn’t in the mood to chat much, but his niece was there to help him get around. A self-described “Republicrat,” he enthusiastically backed Trump in his prior campaigns and Jean King Battle told me her uncle has a lifesize cutout of Trump in their family room “because he’s family to my uncle.” When I approached him the next day, he seemed unaware we were scheduled to talk.

But Trump was right about one thing: The place had strong MAGA vibes and they were feeding off the testosterone in the room.

“That’s my n—a,” boxer Adrien Broner, 34, said when Trump was mentioned at the weigh-in. When I asked him to elaborate, he said, “Trump’s the man. When Trump was in office, everybody was eating.” Dressed in a taxi-yellow sweatsuit with “WORK OR DIE” on the back he added, “He’s a man that means business. Just like me.”

A promoter at the event, Egypt Brown, characterized Trump’s allure in the boxing world as rooted in masculinity. “They don’t connect with Pride month as a fighter,” Brown told me. “They don’t connect with women fighting with men in their sport because it’s all about competition.”

I’d heard similar things in Philadelphia just days earlier, when Republican Reps. Byron Donalds and Wesley Hunt hosted a “Congress, Cognac, and Cigars” gathering at a smoking lounge to discuss Black male politics. Democrats’ emphasis on LGBTQ issues was helping drive Black voters to Republicans, Donalds said, while an audience member complained to me that feminism was leaving Black men behind.

“They intentionally promote the Black woman so she can look down on the Black man,” said Michael Blackwell, 60. “So not only is society looking down at us, now the Black woman is because she got a hundred thousand dollars, got a career. She’s been conditioned to not need a man.”

Kadia’s view

My 1980s road trip through Donald Trump’s star-studded world may wind up being a sideshow — just another journalist’s half-futile attempt to understand the direction of the American public. Or it may be a kind of early warning system of something deeper.

Leaders across the political spectrum are scrambling to channel the shifting politics of gender and a sense that men, in particular, have become alienated from the political system. Republicans have long argued that Black voters are more socially conservative than their vote indicates; their hope is that making elections a referendum on traditional masculinity will find a receptive audience.

A big question is whether Trump has an operation ready to capitalize on his polling: The Biden campaign pointed to the newly revamped RNC’s struggles to nail their own program, including an initial decision to close minority outreach centers.

Trump’s effort is still in its early stages and has been stymied by a lack of direction, with no dedicated lead for ethnic and faith-based outreach. The campaign tapped Gina Carr to focus on Black outreach around the time of his South Bronx rally last month, which was touted as a show of his dedication to reaching nonwhite voters. But it’s still not clear the level of resources or scheduling the campaign plans to roll out, or whether it might release a targeted policy platform for Black Americans like 2020’s “Platinum Plan.” Lynne Patton, his senior advisor, said in a statement that his “pledge to Black Americans” would be to “reinstate” his old policies on issues like the economy and immigration.

But no one should assume Black voters are permanently immune to the kinds of appeals that have worked for similarly positioned white voters — that Trump’s business success translates to success overseeing an economy, or that his personal problems equate to their personal problems, or that his distrust of the “deep state” echoes their suspicions about government or media or corporations. Trump would hardly be the first candidate to try to beat an unpopular incumbent by feeding voters’ frustrations, avoiding policy specifics, and asking them to project their hopes on him.

I asked Tyson about his interactions with ordinary people when it comes to Trump. He told me fans he meets are skeptical, but that his relationship with the former president makes them curious if they’re missing something.

“Street people, they say ‘Yo, I don’t f— with your man [Trump], but he loves you,‘” he said. “They want to meet him. They ask me ‘what is he like?’”

And what does he tell them?

“He’s a people person,” he said. “The common people voted him into office. It wasn’t no big shot that voted him in office.”

Room for Disagreement

Not everyone buys the premise that Trump’s gains with Black voters in polls will translate to the real world. While he has some concerns about younger voters, Democratic pollster Cornell Belcher told me that about 14% of Black men have typically voted Republican in non-Obama cycles and he’s seen little in his own polling of likely voters — and especially in recent election results — to indicate this will change in a major way.

”[There] is literally no evidence in actual voting that Black voters, including Black men, are somehow historically breaking Republican,” Belcher said.

Notable

- South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, a potential vice presidential pick for Trump, helped launch a new $14 million super PAC push this month aimed at Black male voters. Scott told reporters he views it as the start of a multiracial coalition of “working class Americans.”