The News

A showdown between China and a coalition of island and European nations is taking place in Kingston, Jamaica this week over the prospect of mining minerals on the seafloor. For now, the industry has the upper hand.

“This is the crunch-time moment,” said Emma Wilson, policy officer at the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an environmental group.

Tim’s view

It seems likely that deep-sea mining could begin in earnest within the next two years. The debate over the emerging industry goes to the heart of a central dilemma of the energy transition, which is that production of the minerals needed to build EV batteries and other clean tech entails its own unavoidable environmental risks.

Deep-sea mining could reduce the need for even more damaging forms of onshore mining; a boom in nickel production in Indonesia, for example, is emerging as a major threat to that country’s rainforests. But it’s not clear that these two forms of mining are indeed mutually exclusive, given the global economy’s voracious appetite for minerals. So the end result could be more mining on both fronts.

Thus far, deep-sea mining has not yet been done at commercial scale anywhere in the world. But a handful of companies — with the backing of China and other countries hungry for a new supply of nickel, manganese, and other minerals needed for the clean energy transition — are ready to forge ahead.

“The notion of a delay or moratorium is nonsense and has zero legal basis,” Gerard Barron, the CEO of Vancouver-based The Metals Company, told me. To go ahead, they need approval from an obscure UN agency called the International Seabed Authority, which hit a legal deadline this month to finalize regulations for the emergent industry and is now negotiating them in Kingston. TMC is happy with draft rules currently on the table in Kingston, Barron said. It plans to file its mining application once the rules are adopted, and is prepared to begin mining by late 2024 or 2025. China holds the greatest number of ISA exploration licenses, and is keen to extend its existing dominance of the critical mineral supply chain to the deep sea.

For now, only Canada, France, Germany, and about a dozen other countries support a temporary or permanent halt, which would require a majority vote by the ISA’s 167 member states. The U.S., which is not an ISA member, has not taken a public position.

Unless dozens more countries commit to a moratorium, TMC’s application — sponsored by the island nation Nauru — will almost certainly be approved, setting off an undersea gold rush. (Although some of its Pacific island peers are opposed to deep-sea mining, Nauru’s government has cultivated a close relationship with TMC executives and stands to reap royalties from its mining activities, according to a Bloomberg investigation.)

Know More

TMC plans to harvest nickel and other minerals held in billions of oyster-sized deposits called “polymetallic nodules” scattered across the Pacific seafloor. Wilson and other conservationists argue the ISA’s proposed mining rules are too weak and contravene existing U.N. agreements against biodiversity loss, including the high seas treaty adopted last month.

The nodules, they argue, serve an important ecological function, and the process of mining them — involving huge harvesting machines connected via pipeline to collection ships on the surface — could cause catastrophic undersea pollution from dust, heavy metals, and noise. The ISA, which has a relatively small staff and budget, is not equipped to adequately oversee mining that takes place deep underwater in remote stretches of the Pacific, Wilson said.

Room for Disagreement

Even if the ISA applications of TMC and other prospective prospectors are approved, they also face the challenge of finding buyers willing to stomach the reputational risk associated with a controversial new industry. Several of the corporations that should be target customers for a new source of battery metals, including Volvo, Volkswagen, BMW, GM, Ford, and Renault, have committed to exclude deep-sea minerals from their supply chains, amid mounting public scrutiny of mineral supply chains. TMC also lost an important partner earlier this year when Maersk, which had previously planned to provide shipping services for TMC, decided to sell its stake in the company.

The View From Paris

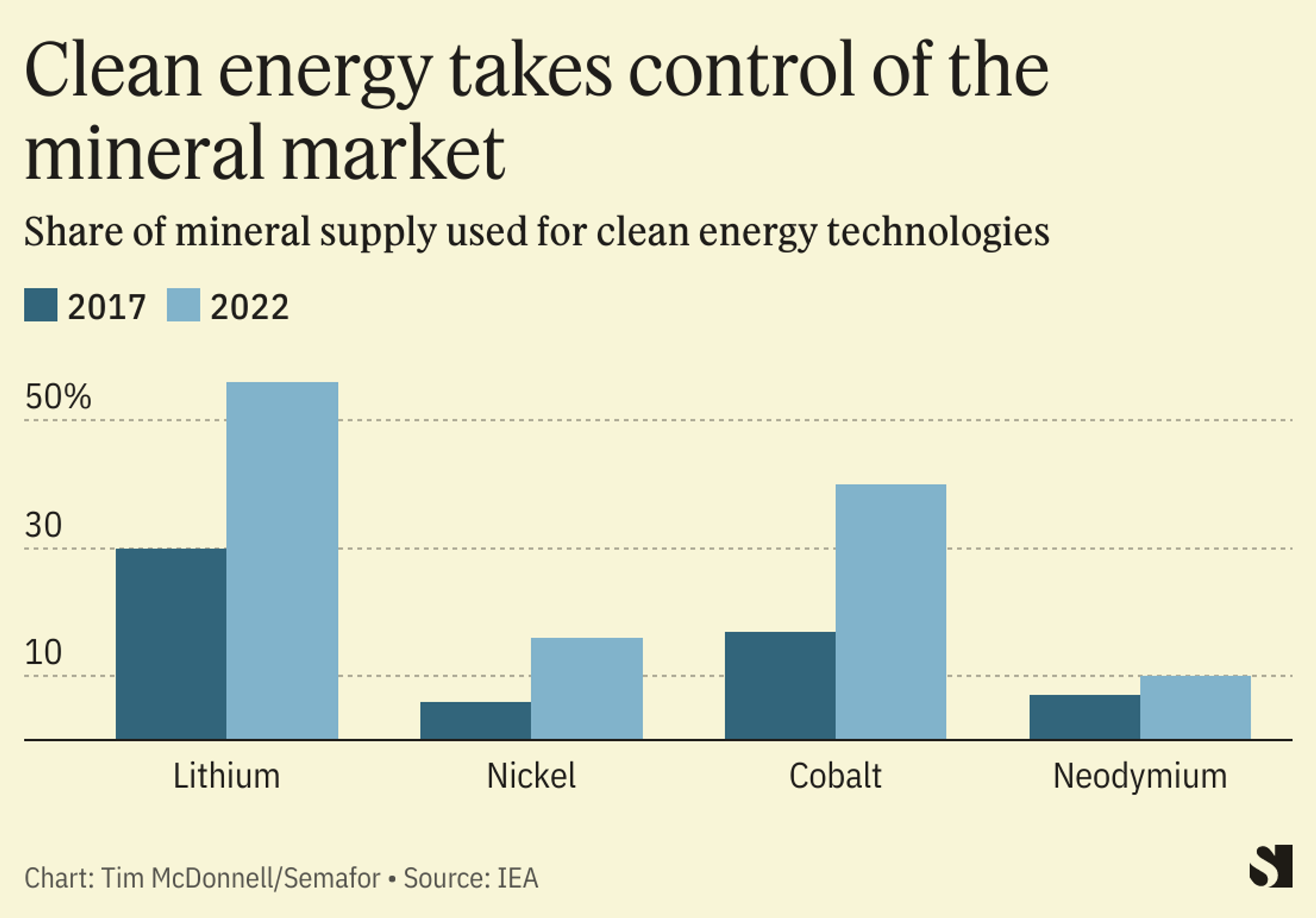

The necessity of deep-sea mining is also being called into question by a deluge of investment in onshore mining. A new analysis this week from the International Energy Agency found that the gap between mineral demand and supply is narrowing as the clean energy industry drove a 30% jump in upstream mining investment from 2021 to 2022.

Notable

- Climate change is making deep-sea mining even more ecologically risky, according to a new study in Nature. Rising ocean temperatures are driving populations of tuna into new locations, including the specific region of the Pacific most prized by deep-sea miners, the study found, concluding that “the potential for conflict and resultant environmental and economic repercussions will be exacerbated in a climate-altered ocean.”