The News

The extreme heat that triggered record temperatures around the world last week is a threat to human health, agriculture, and electric grids — and it’s raising calls for new forms of insurance to cope with the fallout.

Tim’s view

Heat waves are a new frontier for the insurance industry, which is already struggling to keep pace with climate impacts like floods and wildfires. But the sector’s traditional ways of assessing and pricing risk aren’t well-suited to covering heat, and could run into the same problems of access and affordability that are plaguing the home insurance market.

Heat is expensive: A study by Dartmouth College economists last year found that heat waves have cost the global economy $16 trillion since 1992 in the form of lost wages, lower agricultural productivity, and other impacts. A separate study published this week by medical researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University estimated that heat-related illnesses add up to $1 billion in health care costs in the U.S. every year.

New approaches are crucial for climate change adaptation. Federal crop insurance in the U.S. Southwest, for example, is becoming more expensive for farmers because of increasing heat-related losses, which amounted to $1.3 billion since 2001, according to research by Anne Schechinger, an agricultural economist at the Environmental Working Group, an advocacy outfit. Rising payouts also raise costs for taxpayers, because the insurance program is heavily subsidized. For now, it still runs at a surplus most years, unlike the federal flood insurance program that runs at a deficit of more than $1 billion per year. But that could change as heat waves become more common and extreme, Schechinger said: “Climate change is making the program more expensive in a way that’s not sustainable.”

There are a few ways to address that problem. One is to phase out some subsidies, so that farmers are more directly exposed to the costs of farming in high-risk areas and thus more incentivized to adopt adaptive measures like heat-resistant seed varieties. Excess premium payments during cooler years could also be used to buy out land in areas with high heat risk, a model that has been used successfully to phase out farming in flood-prone areas, Schechinger said.

Another possibility is to change the way heat-related payouts are allocated, from the current system in which they are based on crop losses to a heat index system in which payouts are made any time temperatures cross a designated threshold. This approach streamlines the system and can rely on historical temperature data and climate modeling to more accurately price premiums for each farm, said Tobias Dalhaus, an economist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. In a study last year of wheat and rapeseed producers in Germany, Dalhaus found that index-based heat insurance reduced farmers’ financial risk by 20%.

The View From India

Index-based insurance is also being developed to shield low-income workers in India from heat-related income loss. From May to June this year, 21,000 women in the state of Gujarat were enrolled in a pilot program sponsored by the Arsht-Rock Foundation Resilience Center, a philanthropic organization, that would pay up to $85 to compensate them for heat-related illness and damage to vegetables or other items they were selling as outdoor vendors. “The idea is that it’s very responsive and quick” in the event of a heat wave, said Kathy Baughman McLeod, the center’s director. But the pilot revealed the challenges of setting an appropriate index, she said: The heat wave India experienced during those months didn’t hit the requisite temperature for enough consecutive days to trigger any payouts. Next year the threshold will be recalibrated, Baughman McLeod said.

Room for Disagreement

A key challenge inherent in designing extreme heat insurance is that a single event can cover vast geographic areas relative to other kinds of weather disasters, so when a payout is triggered it can easily consume the entire pool of available capital collected through premiums. That problem caused the collapse of a short-lived heat insurance program for livestock herders in Kenya in 2021. So any new insurance programs for extreme heat should also be coupled with other subsidized heat adaptation measures — specialized seeds for farmers, or refrigerators for the vendors in India, for example — to take some pressure off the insurance program itself.

Notable

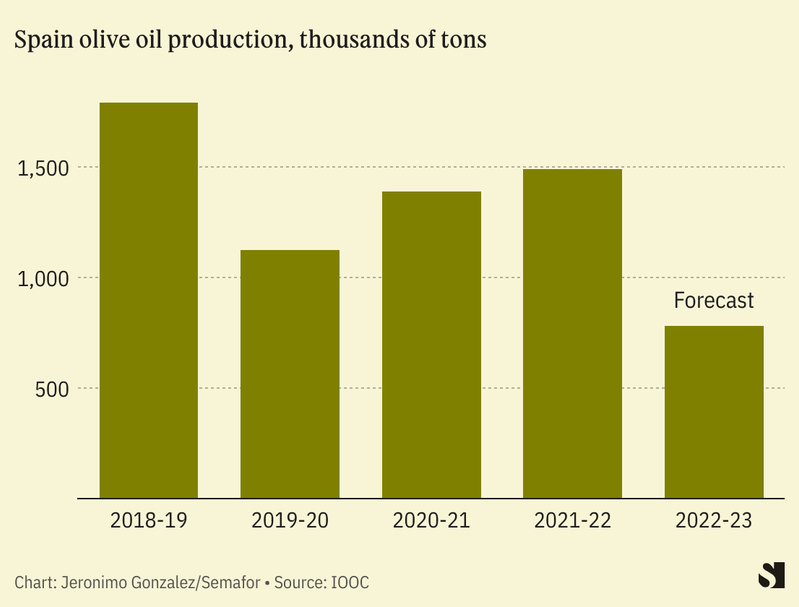

- One industry that is reeling from this year’s heat waves is olive oil. Last year’s harvest in Spain was already the worst in a decade because of excessive heat and drought, and is on track to fall again this year, causing wholesale prices for European olive oil to double.