The News

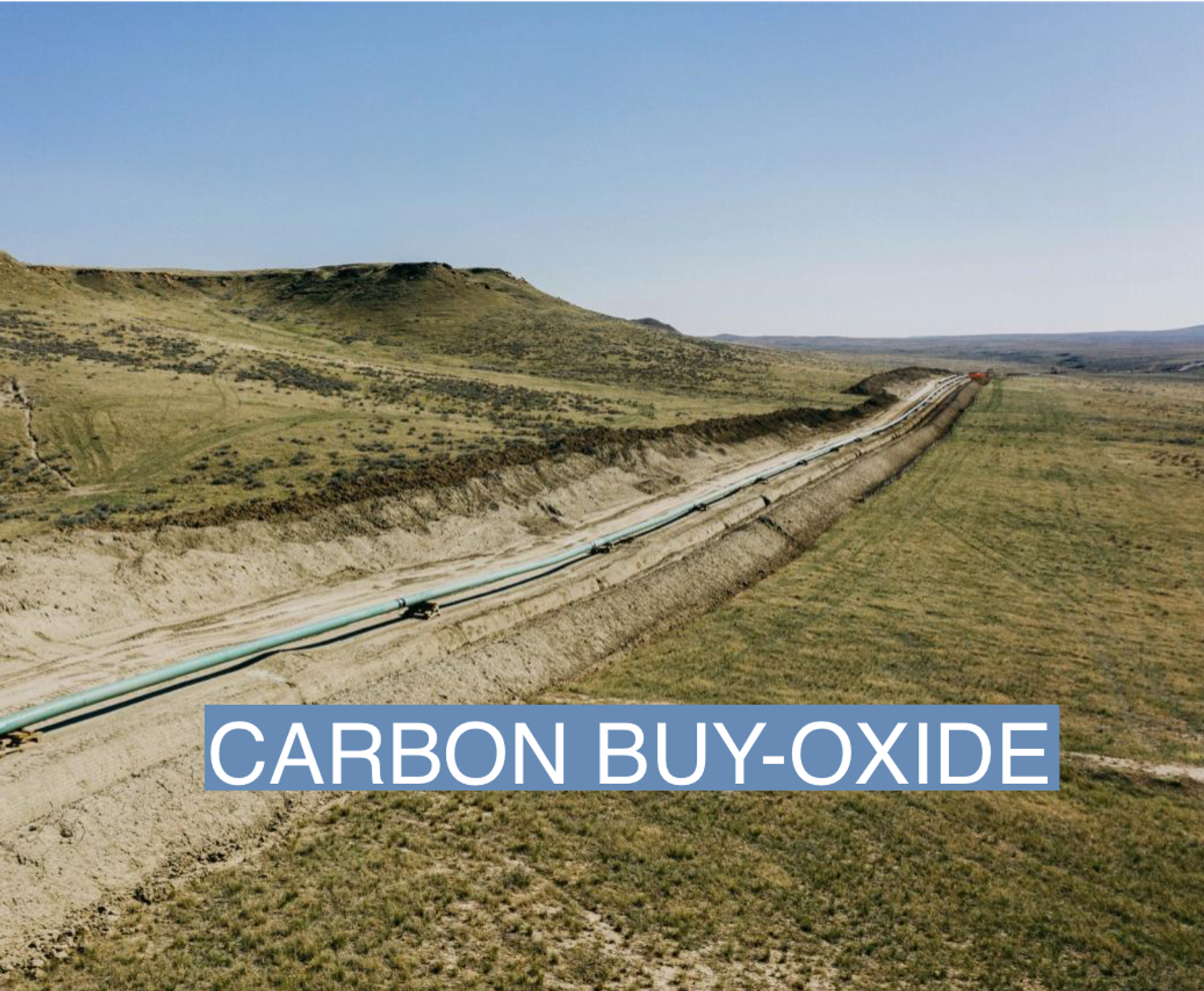

ExxonMobil staked out its vision for its transition to a lower-carbon business model when it spent $4.9 billion to acquire Denbury, a smaller Texas oil and gas company with the U.S.’s largest network of pipelines designed to carry carbon dioxide. The acquisition signals the momentum growing behind “carbon management” as an enterprise that fits better with the traditional strengths of oil and gas companies than renewable energy.

Tim’s view

The Denbury acquisition last week is a show of confidence by Exxon that carbon capture and storage (CCS) will really take off across the electricity and manufacturing sectors in a way that up to now has proven cost-prohibitive, and provides a green light for other companies that want to capture and store CO2 to dive in.

Exxon’s vision is that eventually these pipelines will ferry CO2 captured from industrial point sources like cement and steel plants, and potentially from natural gas power plants, and transport it to underground rock formations or old oil wells where it could be buried (Denbury also owns a number of large sites for carbon sequestration).

Companies that want to use CCS to lower their carbon footprint could turn to Exxon as a one-stop carbon disposal shop. Exxon is already building up a portfolio of this kind of business, signing several carbon management deals in the last year with chemical and steel companies. The Denbury acquisition will allow the company to “accelerate the growth of this business and do that on a very profitable basis,” Dan Ammann, president of Exxon’s low carbon solutions division, told Bloomberg.

Carbon management is becoming increasingly popular with oil companies, since it plays to their know-how in trading, transporting, and storing molecules (as opposed to electrons from renewable energy, which are an entirely different business). The Denbury acquisition, which is the largest single carbon management investment by any company to date, allows Exxon to jump ahead of competitors like Oxy and Wintershall Dea in seizing control of the relatively limited supply of existing carbon-moving infrastructure. That’s critical since the construction of new CO2 pipelines is no easier to get approved than an oil pipeline. It also allows Exxon to tap one of the most lucrative tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act: $85 per ton of CO2 that is permanently stored underground.

So far, Exxon’s overall low-carbon spending has ranked among the lowest of U.S. and European oil majors, accounting for just 0.5% of its total capex since 2015, according to Bloomberg. For a company that turned a $56 billion profit last year, $5 billion is still a drop in the bucket. But it’s a clear sign of where the industry is headed.

“Exxon, by virtue of its size, is a bellwether,” said Neil Quach, an oil and gas analyst at the think tank Carbon Tracker. “I do think other companies should and will follow suit.”

Room for Disagreement

For now, Denbury’s pipeline network isn’t really low carbon, but instead will function as an extension of Exxon’s normal oil business. Today the CO2 carried in the pipelines is used for “enhanced oil recovery,” a process in which it is injected into oil wells to push out the last few drops. EOR has helped make the expensive CCS process viable in its early days, and even with IRA incentives, giving up the revenue from EOR oil sales will make CCS a risky bet, especially for industries like steel and cement where the CO2 concentrations in their smokestacks are much lower than in natural gas processing, which is today the most common CCS platform.

The upshot is that the carbon management industry needs to scale as quickly as it can in the next decade while IRA incentives are still available, said Julia Attwood, head of sustainable materials at BloombergNEF.

The View From London

Carbon management took another step forward this week with the launch of Isometric, a London-based startup that will run a registry of certified carbon removal projects. These projects are different from Exxon’s focus, in that they involve removing CO2 from the atmosphere instead of capturing it from point sources. But the registry serves the same big-picture purpose as the Denbury acquisition, which is to facilitate the nascent carbon trade.

Notable

- While it takes baby steps on the energy transition, Exxon is still taking big leaps with fossil fuels. The company plans to double the size of its liquefied natural gas business by 2030, an executive said this week, with a focus on buyers in Asia.