The News

Investors and businesses are increasingly focusing on an often-overlooked material — graphite — because of its vital role in batteries, storage technology, and the potential fortune to be made in undermining China’s overwhelming dominance of its production.

Graphite is a key element in lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles and other devices that require energy storage. China’s monopoly over its production, refining, and export is worrying executives looking to diversify their supply chains and could see it emerge as a potential flashpoint between Washington and Beijing.

“Twenty four months ago, all the conversation was about more energy-dense batteries,” Keith Norman, chief sustainability officer at Lyten, an advanced materials company that is one of several looking to replace graphite in batteries, said in an interview. “Then, in the middle of last year, we started to see talk ramp up around resiliency of the supply chain.”

The topic of shifting away from graphite in batteries is now, “if not number one, right behind it in terms of the primary conversation we’re having,” Norman said.

In this article:

Know More

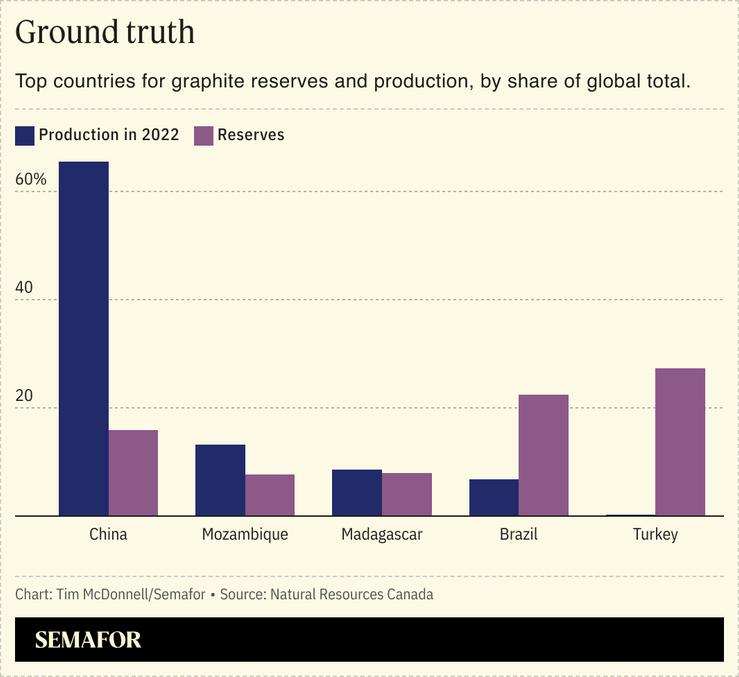

Graphite is necessary for the anodes in lithium-ion batteries, comprising up to a quarter of the weight of those used in electric vehicles. And China is the world’s dominant player, responsible for more than 90% of the refining of the graphite used in the batteries.

In December 2023, Beijing added graphite to a list of items that require an export license, a move widely interpreted as a response to growing curbs by Washington on China’s access to advanced semiconductor technology. Buyers of battery-grade graphite responded by stocking up on the material ahead of the new rules, sending prices surging by more than 150%.

Experts have debated the impact of the export-license requirement — unlike the US’ restrictions on selling chip manufacturing equipment to China, Beijing’s rules do not target particular countries, and authorities have so far approved export requests — but the fact they have been instituted at all underlines China’s dominance over the battery supply chain, and in particular that of graphite.

Ultimately, policies like Beijing’s underscore the importance of “friendshoring,” two experts at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies wrote after the license requirement was announced last year.

The trouble with minerals, in terms of geopolitical supply chain diversification, is that wherever they are, they are. And the world’s graphite supply is heavily concentrated in China, Turkey, and Brazil. Unlike, say, the construction of solar modules, the US will never be able to compete directly with China on graphite. Instead, US entrepreneurs want to pull off an innovation end-run around China by making graphite obsolete.

Lyten aims to refashion battery chemistry from lithium ion to lithium sulfur, replacing the traditional reliance on minerals such as nickel, cobalt, manganese — and graphite — with a sulfur cathode and a lithium-metal anode. Another firm, Group14, uses a silicon-carbon composite as an alternative to graphite in lithium-ion batteries.

Though the pair have different strategies, both have big-name investors — in Lyten’s case, FedEx, Stellantis, and Honeywell; for Group14, Porsche and Microsoft — and argue the only difference customers will see is improved performance. Lyten is aiming to have its batteries in e-bikes and scooters next year, trucks by 2026, and EVs the following year; Group14 projects vehicles with its technology will launch in 2025.

Prashant’s view

China’s control of the graphite supply chain remains a major issue in the battery industry. Much as it does with solar and wind power, China’s heft in the energy transition has its own gravitational force: In both sectors, a combination of official direction, state largesse, and private entrepreneurship has created an industry that either dominates globally, or is on its way to doing so.

The question when it comes to graphite and batteries is whether Beijing can be beaten, given its more than decade-long head start developing companies with cutting-edge intellectual property, forged through cut-throat domestic competition which has forced them to hone their products, cut excess costs, and finetune their strategies.

Companies like Lyten and Group14 are leaning into business models that reduce Western dependence on graphite from China, betting that if unseating the country’s dominance is indeed possible, it won’t be by building industries that directly compete with China’s own behemoths, but by developing new technologies that allow battery customers to choose to sidestep China.

“We are very much focused on” supply chain diversification, Grant Ray, Group14’s vice president of global market strategy, said, “because it’s a lot of what our customers are asking of us.” He continued: “China does come up… Is there a geopolitical slant to it? Of course there is.”

Ray went on to say that companies similarly did not want to rely on individual US states, and Norman noted that Lyten’s clients were wary of any single country that monopolized part of the supply chain, whether or not that was China.

To some degree, they are both correct. A vulnerability exposed during the pandemic was excessive reliance on any single place for the global supply of anything: In early 2020, for example, the world depended on Lombardy in northern Italy — initially, the biggest COVID-19 hotspot in Europe — for swabs that would help test for the virus.

Room for Disagreement

Global demand for battery energy storage is such that the choice is not so much either-or — between China’s control of graphite production and alternatives to the material — but yes-and, requiring all such technologies and processes for different uses: That was an argument put forth by both Norman and Ray.