The News

Kamala Harris’ ambush of a presidential campaign has raised a question that American political types have long brushed off in conversations with puzzled foreigners:

What if our campaigns were much, much shorter?

In this article:

Ben’s view

The presidential campaign is currently a two-year cycle, which begins just after the prior midterm elections. There are a number of reasons for this bloat I won’t revisit in detail, but revolve around the imperatives of fundraising and boxing out rivals, and feeding an overgrown media machine (sorry!).

But there are also downsides: Your rivals attack you for months. You face steady pressure to remake yourself for your party’s activist base. Journalists have many months to dig very deep on your record and your life. The public can really get sick of you. Your staff can get sick of each other.

Harris is accidentally demonstrating the alternative: She’s the hot new thing in August, riding on vibes and goodwill six months after the Super Tuesday peak of modern campaigns. When she holds a convention next week, it won’t just be a high-production finale of a long season. Viewers will be turning in to figure out who she is — and she’ll tell them. Major party figures like Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Bill Clinton will be talking about her candidacy for the first time, not the nth. She has a shot at extending what seems like her biggest advantage over Donald Trump right now: her success at controlling the conversation on both social and legacy media.

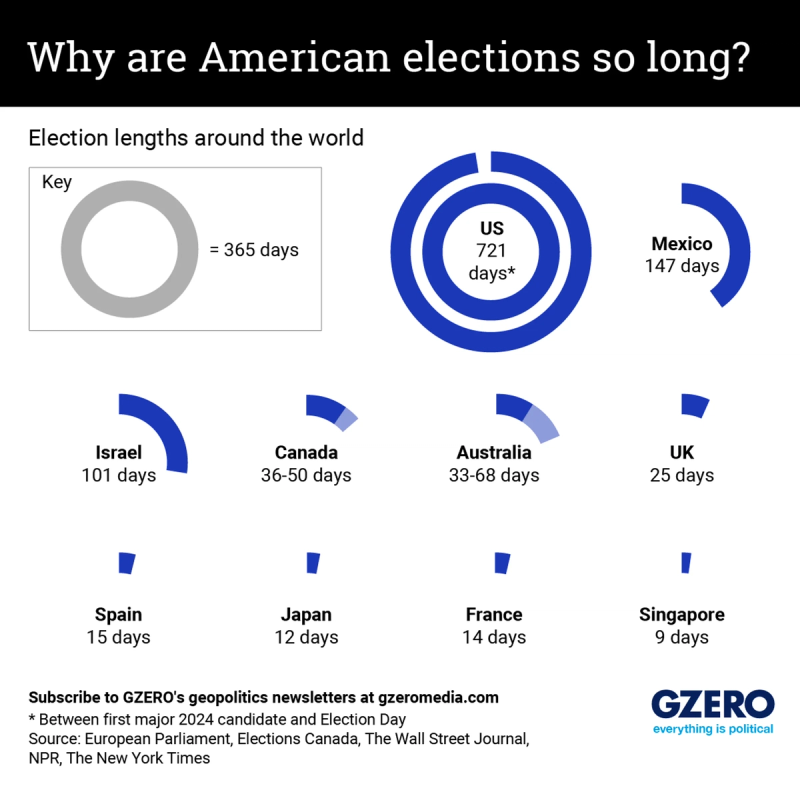

Party insiders have noticed. “Presidential campaigns were never meant to be two years long, but for a variety of reasons, such as the media’s love of horserace and the burgeoning consulting industry in the US they became that,” one Democrat in the center of this storm reflected Monday. “They are an overly long slog for the people who work on them, the candidates, and the public. Most countries have shorter campaigns that last weeks or a few months, have plenty of debate and scrutiny, and result in clear and healthy outcomes.”

The political parties could easily institutionalize this kind of shift. They could jam all the state-by-state primaries, perhaps in regional groupings, into July. That would dominate the summer, and turn the convention back into a news event, not just an extended, televised rally.

Room for Disagreement

There are a lot of reasonable objections to this, which popped immediately when I floated this on X.

The countries that Americans often cite as models — the UK and France in particular — have far more closed party systems, in which decisions get made, to some degree, by pragmatic, victory-minded elites, not a broader electorate. One issue with moving in that direction is that American elections are incredibly expensive, with an early start that’s required to raise money, meaning it’s hard for one party to unilaterally go late. But shorter campaigns would also be far cheaper — a month of payroll, a month of ads.

Another objection to my theory is that all the damage a candidate takes in the primary would be compressed — with no time to recover. We got a preview of that during the two-week scramble to select a VP, which energized the party with more fresh faces but also got bogged down into an opposition research battle by the end.

But two-party American politics are zero sum. If one party adopted the compressed schedule, dominating voters’ attention in the summer and fall, the other party might be forced to follow suit. The consequences would be hard to predict, and the only obvious losers would be political consultants and admakers. Sorry!

And … well… the media. But we can take it.

Notable

- Ground Zero notes that other nations’ election periods range from 147 days in Mexico to 9 days in Singapore (where the outcome is less...in doubt.)

- The long campaign is a product of reforms which, Julian Zelizer notes, “failed to stop the escalating costs of elections.”

- “Longer campaigns pretty well ensure that candidates will be vetted—that voters will know their strengths and flaws and key issue stances before casting a vote,” Seth Masket writes in defense of the status quo.