The News

Some 500 miles west of Beijing, in the desert of the Chinese region of Inner Mongolia, a solar-power project is underway that is — even by China’s standards — audacious in scale and, most remarkably, in ambition.

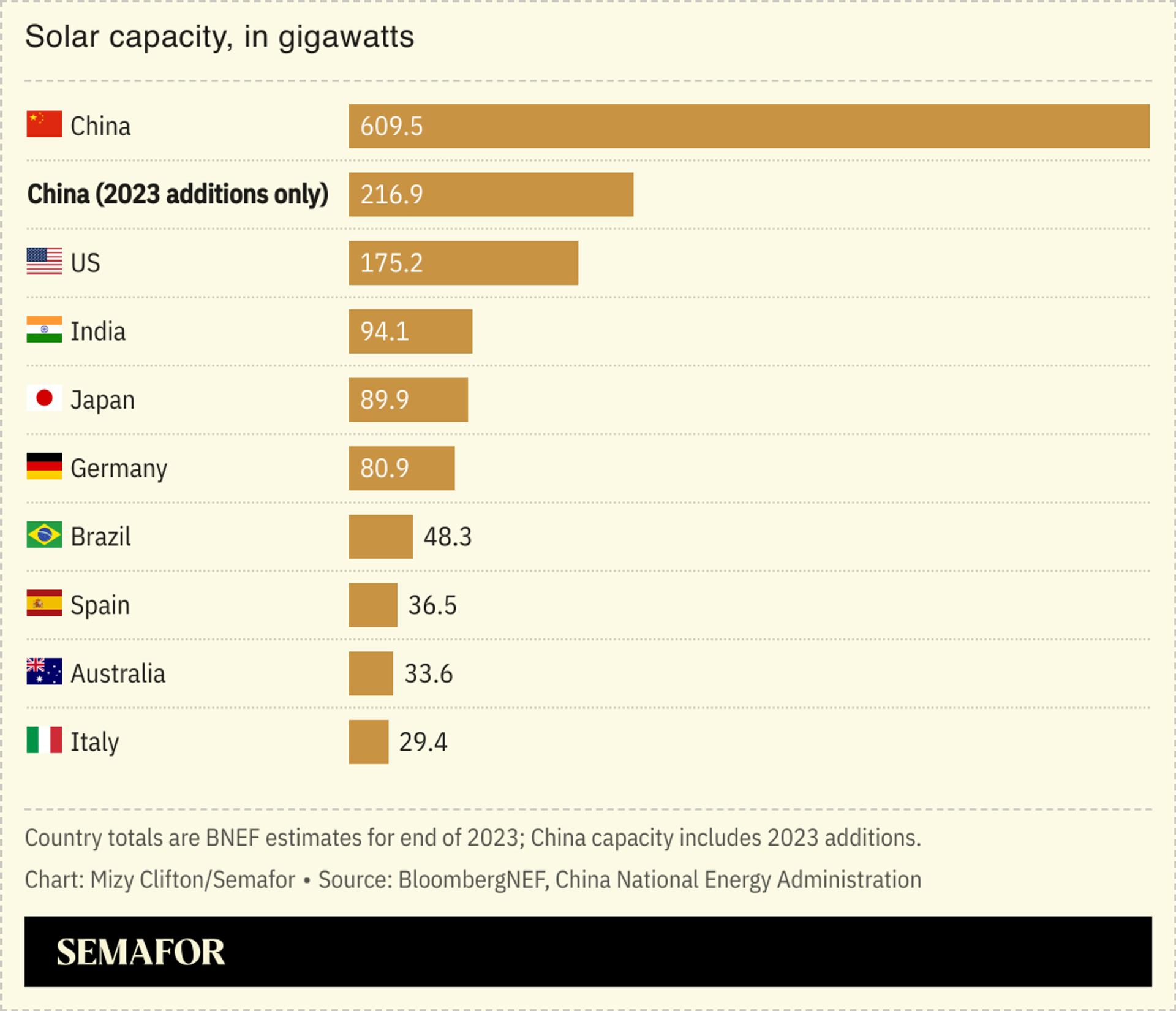

Officials in Ordos are over the next several years going to install 100 gigawatts of solar panels — more than three times as much capacity as the United States is currently building nationwide — along a stretch of land 250 miles (400 kilometers) long and 3 miles (5 km) wide.

The goal isn’t just to generate huge amounts of clean power. It is also to restore a no man’s land, bringing greenery and even livestock to an area roughly the size of Puerto Rico. In doing so, the local authorities are doubling down on two of China’s most successful efforts of recent years: An epic expansion of solar power, and major progress in combating desertification.

Xiaoying’s view

China’s central role in the expansion of global solar power capacity is well understood: Its dominance of the industrial chain from the production to installation to repair of panels globally is such that Western trade bodies have pressed policymakers to slap tariffs on Chinese solar companies. Analysts fret that Chinese “overcapacity” in the country’s solar production will lead to ruin (though experts at the energy think tank Ember say that, with climate challenges pressing globally, “underutilization” is a more appropriate term than “overcapacity”).

Less well appreciated, though, is the attention Beijing has devoted to fighting desertification, and how, in its view, the two increasingly go hand in hand.

China’s deserts equate to more than a quarter of its total land mass, amounting to almost as much territory as all of India, and since the 1950s the country has been seeking to mitigate the severity and impact of dust storms, and over the longer term, to prevent desert encroachment on urban areas, or fertile, arable land. As climate change makes desertification worse globally, Beijing is upping its focus on the challenge.

On the surface, the logic is straightforward, combining a relatively low-maintenance, clean power generation technology with swathes of cheap land abundant in sunlight. The reality is more complex: Chinese companies have been trying to deploy vast solar farms in the country’s deserts for more than a decade, with varying degrees of success.

In recent years, however, they have begun to show major progress. The stakes are high: With the world aiming to triple its renewable power capacity this decade, a major country able to deploy solar power at mass scale in the desert would have huge implications globally.

Know More

The mammoth six-year project in the Kubuqi Desert near Ordos, Inner Mongolia — once known as China’s “coal capital” — is the culmination of years’ of progress by the country’s solar developers.

Initially, those operating in desert climes adopted measures such as creating sand barriers and planting trees in order to safeguard their operations. “They must take actions to minimize the damage they would bring to the local ecology and environment while also protecting their own bases from being damaged by sandstorms,” Wang Weiquan, the general secretary of the Energy and Environment Committee of China Energy Research Society, a Beijing-based NGO, told me. “Much to their surprise, they found that their work led grass to grow in the desert.”

Indeed, according to a 2022 study, desert-based solar power projects have resulted in “a significant greening trend”: About one-third of the land under solar plants built in 12 Chinese deserts has seen vegetation grow.

As another recent study showed, solar panels do not only create shade, enabling plants and vegetables to grow, but also reduce the ground wind speed, preventing sand from being picked up.

Solar companies saw opportunities: They started to search for suitable crops to grow under the panels. One plant they found worked was liquorice, which can survive in the harsh environment and make the soil more fertile by absorbing nitrogen from the air and converting it to the ground.

One solar farm in the Kubuqi run by Elion Resources Group, a Chinese company specializing in restoring deserts, also grows potatoes, melons, and keeps sheep. The agricultural work not only helps sand stay in place, but also addresses two other national Chinese campaigns: poverty alleviation (because it can provide jobs to local laborers) and enhancing food security.

Since 2017, several major solar companies, such as Longi, have built demonstration projects in the desert to showcase their ecological and social benefits. They have also continued to update their products to make them work better in extreme weather: For example, a huge two-gigawatt solar power plant in the Kubuqi was connected to the grid last December, using double-sided panels to increase power generation and eschewing traditional supporting frames in favor of long wires holding a row of panels from both sides to allow for more space underneath to grow food and rear livestock.

More recently, a May notice from the central government instructed northern and northwestern regions to prioritize using “unmanaged desertified land” to build desert solar fleets.

Room for Disagreement

China plans to send solar and wind power generated by inland desert bases to power-hungry economic hubs, which are largely situated near the coast, via ultra-high-voltage transmission lines. But the construction of these lines has been slow and not enough of them have been planned, Yu Aiqun, a senior analyst with Global Energy Monitor, a California-based NGO, said. Plus, the strategy relies on coal power to mitigate the unstableness of renewables, which undermines China’s clean energy development, Yu noted.

There are also environmental concerns. For one, most Chinese developers build their desert bases by bulldozing sand dunes, and this could ultimately lead to sand and dust storms, a Chinese sand-control expert told me, speaking on condition of anonymity. A previous study also showed that covering the Sahara with solar panels may, in fact, worsen global warming by potentially increasing surrounding air temperatures markedly and reshaping rainfall patterns worldwide.

The View From Nigeria

Although China has yet to bring any major solar-plus-sand-control projects to Africa, the continent “could potentially benefit” from the model, Labake Ajiboye-Richard, chief executive of the AR Initiative, a Nigeria-based sustainability advisory firm, told me. “It could help address energy needs while also tackling environmental challenges… [and] attract investment and create jobs,” she said.

But it is “crucial” that such projects are implemented in ways that prioritize local interests, environmental sustainability, and long-term economic benefits, Ajiboye-Richard noted.

Notable

- Solar farms along a desert highway in China’s Xinjiang have been powering wells to extract groundwater and irrigate sand-fixing trees. But such projects can also cause water stress in an extremely dry region, as Niu Yuhan and Sam Geall explain in Dialogue Earth.