The News

Ecuadorians voted overwhelmingly to halt the development of new oil wells in the Yasuní National Park in the Amazon, one of the most biodiverse regions in the world.

Almost 60% of voters favored closing the oil field run by Petroecuador, the state-owned oil company. In a separate referendum, voters also elected to axe six permits for mineral mining close to the capital of Quito.

SIGNALS

The Yasuní National Park — which covers more than a million hectares and is home to several indigenous communities as well as hundreds of species of animals — was designated a world biosphere by Unesco in 1989. Protecting the park’s diversity was the decade-long priority for the referendum’s advocates. “Oil exploitation in Yasuní should always have been prohibited• 1 , not only because the people there live in isolation but because it’s a protected area,” an Indigenous community spokesperson said.

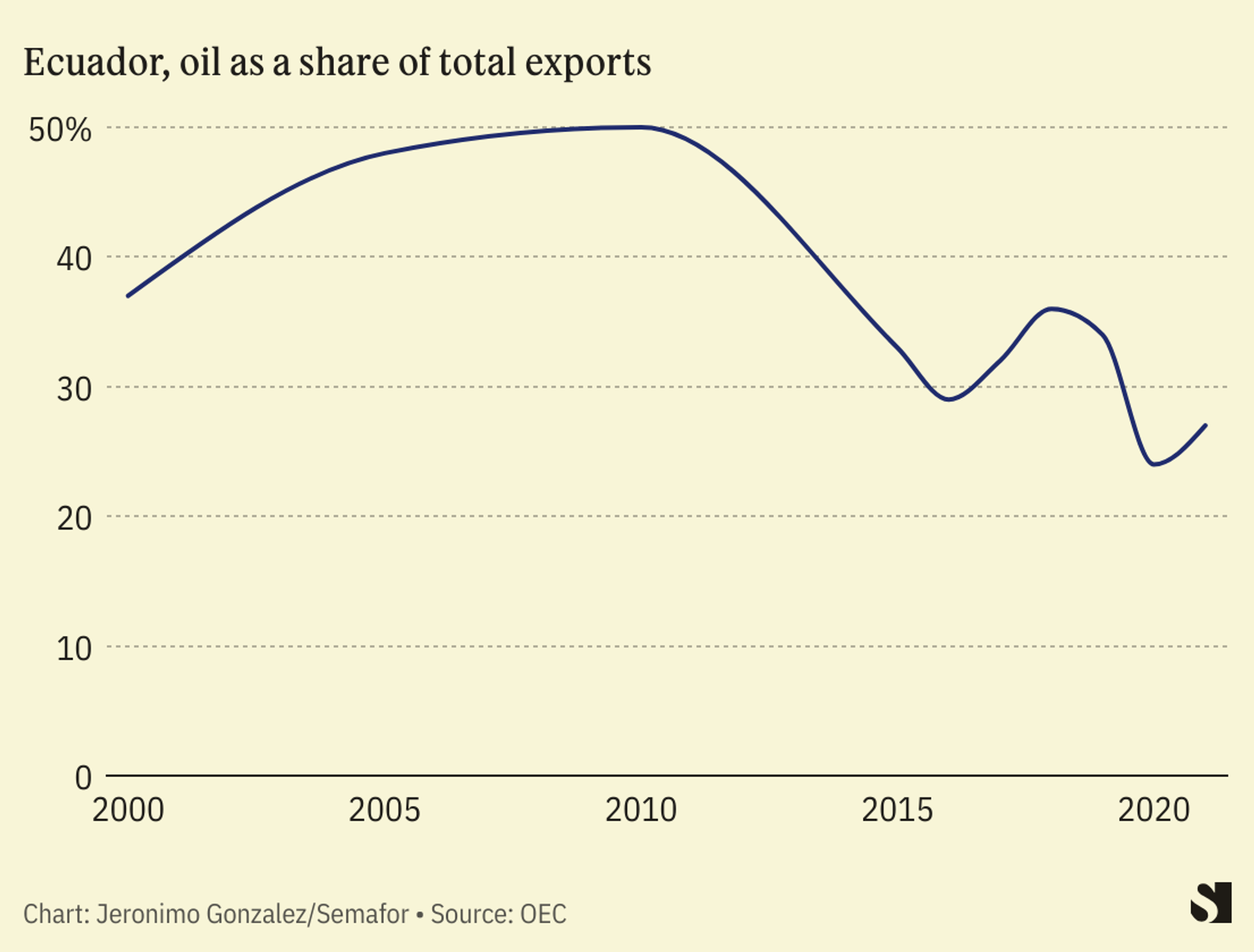

Petroecuador has said the vote could cost the economy almost $14 billion in lost income over the next two decades, money that critics of the referendum's result said could have helped fund health and education needs. Oil remains Ecuador’s biggest export by a significant margin, despite halving as a share of total exports since 2010. Oil and mining guilds say such bans will worsen the economy and encourage illegal mining and deforestation. The referendum "doesn't help any oil or mining investment, nor any foreign investment,• 2 " Maria Eulalia Silva, head of Ecuador's Chamber of Mining, told Reuters. "You cannot protect the environment when you have communities caught in poverty."

Scientists fear that continued deforestation of the Amazon could push it beyond a tipping point where it becomes a net emitter, rather than absorber, of greenhouse gas emissions. However, leaders of eight South American countries that are home to the Amazon couldn’t agree to a commitment to stop deforestation of the rainforest by 2030. “We’re living in a world which is melting• 3 . We are breaking temperature records all the time. How can it be that in a 22-page declaration the presidents of eight Amazon countries can’t clearly state that deforestation needs to stop?,” Marco Astrini, the head of the Climate Observatory group, said.

The Guardian, Amazon leaders fail to commit to end deforestation by 2030