The News

A Nigerian company backed by Silicon Valley’s top startup incubator hopes to prove food delivery apps can take off in an underserved market littered with failures.

African e-commerce firm Jumia stopped delivering food in seven countries last December, as did Estonian ride-hailing platform Bolt in Nigeria and South Africa.

But business is booming for Chowdeck, a food delivery app created three years ago that operates in Nigeria. It has doubled its daily deliveries to 40,000 in the three months since it raised $2.5 million from investors that included Y Combinator, Chowdeck’s chief executive Femi Aluko told Semafor Africa. It was Nigeria’s most downloaded food delivery app in the last month, according to tracking platform Similarweb.

Chowdeck’s new partnership strategy may partly explain the surge and offer a model for success. Earlier this month it reached a deal to exclusively deliver orders from Chicken Republic — one of Nigeria’s largest fast food chains — in the southern cities of Lagos and Ibadan. Aluko said deals with other chains are in the pipeline.

Other delivery services are competing in Nigeria. After two years operating a grocery delivery service in Nigeria, Angolan company Mano began delivering food in Lagos and Abuja this month. Glovo, a Spanish outfit that launched in Nigeria in 2021, reported a 166% increase in jollof rice orders on its app last month.

The International Market Analysis Research and Consulting estimates that the Nigerian food delivery sector was worth $936 million as of last year. The sector is poised to shoot past $2 billion by 2032, the research group said.

In this article:

Know More

Chowdeck’s motorcycle delivery riders operate in eight Nigerian cities, although Lagos accounts for seven in 10 orders. An average order is about 4,000 naira ($2.50) in the Yaba area of Lagos regarded as home to Nigeria’s innovation ecosystem, but up to twice that amount in some interior parts, Aluko said.

Using software to understand customer demand trends and predict the routing of riders, who deliver 12 orders per day on average, to pick up locations is key for efficiency, Aluko told Semafor Africa. He also said the startup has developed a more precise digital map in-house, using the open source service OpenStreetMap, because Google Maps has not fully served the company’s needs for accurate directions.

On expansion, Chowdeck wants its operations in existing cities to be profitable before new ones are started. “It takes three to four months for us to become profitable in a new city,” Aluko told Semafor Africa.

Alexander’s view

Bursts of growth like that experienced by Chowdeck in recent weeks illustrate the expanding reach of locally developed digital technology services in Africa. Mobile money and cashless payments attract the most attention and investment in the continent’s tech scene, but changes in how people buy food online offer opportunities for growth.

The tricky part is identifying the best business model.

Chowdeck started off focusing on street food vendors that offered local delicacies. But while that class of vendors remain dominant on the app, much of its recent growth could be attributed to preferential or exclusive deliveries from popular fast food chains as well as discount offers to customers. For the young student or worker who “understands the value of time” — as Aluko describes Chowdeck’s typical user — the majority of orders arrive within 30 minutes.

Beyond tech and marketing strategies, however, Chowdeck and other current food delivery players also owe their performance to a Nigerian market more prepared for the service, says Osarumen Osamuyi, founder of African tech analysis platform The Subtext.

“My hunch is that the market has been caused to mature by the activities” of earlier players, Osamuyi said. Where Jumia Food started by offering payment on delivery ostensibly to build customer trust, Chowdeck can now take for granted that there is enough confidence in Nigeria’s online payments system to pay before delivery, he said.

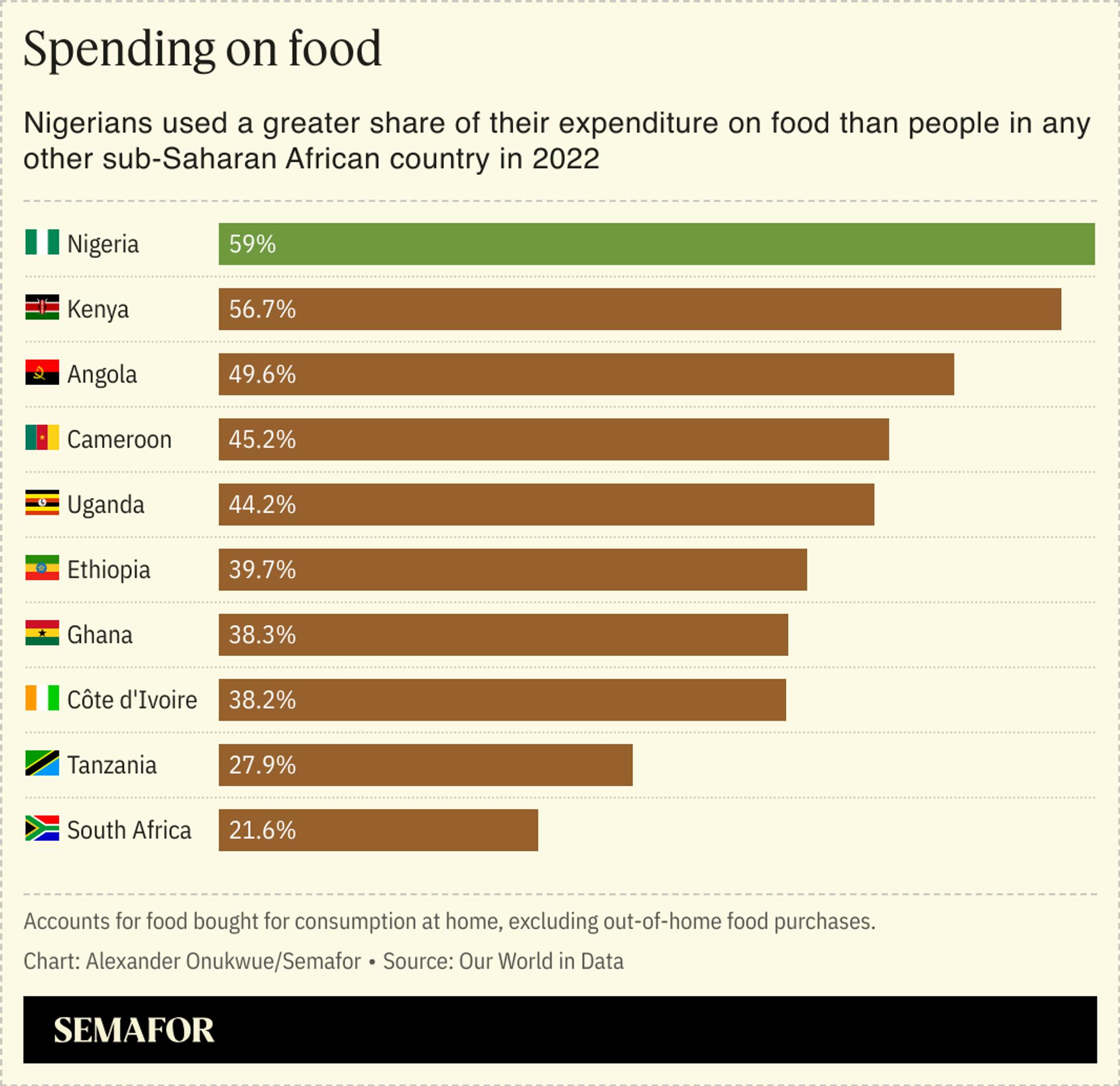

Nigeria’s inflation rate of 33.4% is at one of its highest levels in three decades, though it slowed in July. As fuel prices rise in the country, restaurants can be expected to push production costs to consumers, leaving food apps vulnerable to price sensitive users. The inflation pressure will reveal a good deal about the resilience of the country’s food delivery sector, Osamuyi said.

Room for Disagreement

Tech-driven food delivery is at an early stage in Africa. It doesn’t boast the multimillion dollar fundraising hauls of startups in fintech and e-commerce.

Last year, Jumia said it scrapped its food delivery business because it had “not achieved profitability since its inception” and could not bear Nigeria’s macroeconomic conditions of soaring inflation and currency devaluation.

Two years ago in Kenya, Kune crashed after barely a year of aiming to fix a street food problem Kenyans said did not exist.

Notable

- Explaining Jumia’s decision to quit its food delivery operation, CEO Francis Dufay said the sector’s low barrier to entry made it “a very unattractive business” for e-commerce companies in Africa whose major focus is to deliver physical goods.