The News

A major climate summit in Nairobi this week zeroed in on how Africa can raise the tens of billions of dollars it needs to adopt clean energy and adapt to the impacts of climate change. One option drawing an increasing amount of attention, money, and criticism: Selling carbon offsets.

On Monday, an investor group from the United Arab Emirates said it would buy $450 million in carbon credits via the African Carbon Markets Initiative, a nonprofit launched last year to facilitate the sale of credits derived from Africa-based carbon-cutting projects. A separate group led by HSBC Asset Management committed to buy $200 million in credits from ACMI.

Africa-based carbon projects — including renewable energy, forest conservation, replacing charcoal cookstoves with clean alternatives, among others — could be “an unparalleled economic goldmine,” Kenyan President William Ruto said in a speech Monday.

“GDP is about capitalizing on what you have,” he said. “We have the carbon sinks that serve the world.”

Tim’s view

On the surface, carbon credits may make sense as a way to raise climate finance for African countries, especially since other sources, whether via private investors or foreign aid donors, are far behind where they need to be. But the existing carbon market is riddled with accounting and social justice problems, and requires more stringent oversight to avoid becoming a contributor to the climate crisis rather than a solution to it.

Africa has a huge climate finance deficit. The continent requires at least $250 billion per year in private investment and foreign aid to beef up its energy system and address climate impacts, but currently receives just 12% of that, according to the Climate Policy Initiative, a U.S. think tank. African countries draw just 2% of global annual investment in clean energy, in part because Western investors see the region as a risky environment.

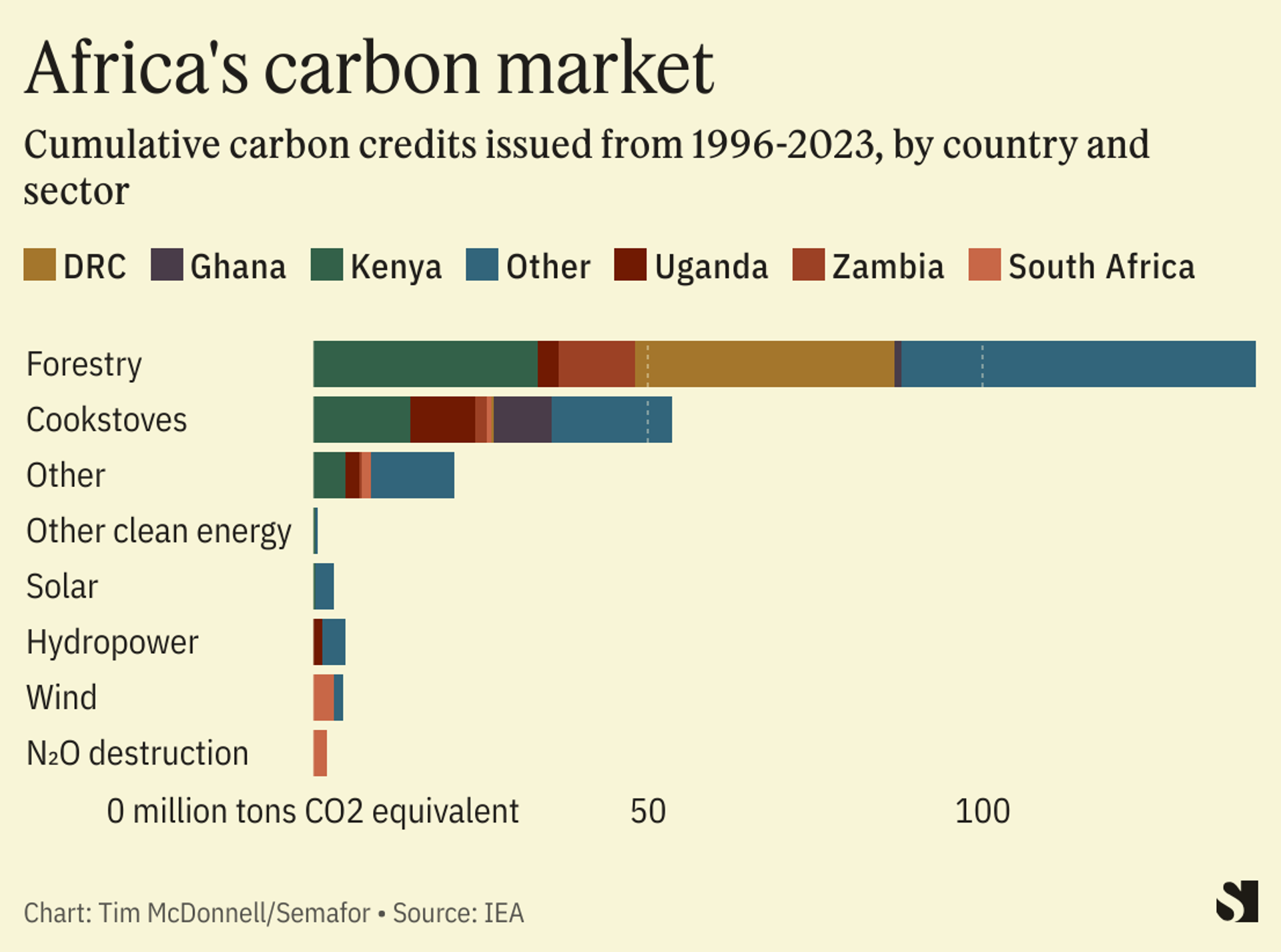

Carbon credits could fill this gap and lower the high cost of capital for African clean energy projects by giving U.S. and European companies, and even governments, an added incentive to put their money into African climate projects: the ability to write down their own emissions. Africa-based carbon credits — predominantly from forest conservation projects — are already routinely sold to Western airlines, energy companies, and other big emitters, although they account for only about 11% of credits on the market globally, according to the International Energy Agency.

Growing that share could effectively convert Africa’s green development into one of its most lucrative export commodities. The ACMI estimates that African countries currently use less than 2% of their annual carbon credit production potential, and could raise $100 billion per year by 2050 through carbon credit sales. That idea was endorsed at the Nairobi summit by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and by U.S. climate envoy John Kerry.

Private companies aren’t the only potential buyers: The Paris Agreement allows carbon project developers to sell credits to foreign governments that they can apply toward their national decarbonization goals. Ghana was the first country to pioneer this strategy, with a carbon credit deal with Switzerland it organized last year. According to the IEA, sovereign carbon credit sales by African countries could raise even more money than sales to companies.

Know More

There are a number of pitfalls facing the carbon market. One investigation after another by academic researchers and journalists have shown that carbon projects in Africa and elsewhere frequently overstate their climate benefit, for example by claiming that the sale of credits helped to “conserve” a tract of forest that was never in danger of being cut down. Watchdog groups say there’s a serious risk of double or even triple-counting, in which a single credit is marked against the carbon footprints of the country that produced it, the company buying it, and the country that company is located in. Efforts to build a U.N.-backed registry to prevent double counting have ground on with little progress at the last several COP summits.

There are also equity problems. Little revenue from the credit sales reaches the country or community in which the project is based — according to the IEA, that figure is often as low as 10% for projects in Africa. Demand for offsets has also led to land grabs in Kenya and elsewhere.

These deficiencies are self-defeating, because they create a reputational risk for credit buyers that could drive them away. Last week oil major Shell said it scrapped a major carbon credit purchasing plan after it failed to find a sufficient volume of high-quality credits.

In a phone interview from Nairobi, Margaret Kim, CEO of carbon credit registry Gold Standard, said that firms like hers and governments of host countries need to do a better job of monitoring and verifying carbon projects, and of involving local communities from an early stage.

At the moment, that kind of oversight is entirely voluntary. That will likely need to change to a system of mandatory regulation from host governments, said Franklin Steves, senior finance policy adviser at the Europe-based think tank E3G.

”[Carbon markets] are an idea that can work in principle, but we’ve seen so many fraudulent cases that I don’t think any policymaker should look at it as a silver bullet,” he said. “There’s an enormous risk that corporations use them as a deflection tactic.”

Room for Disagreement

Some African countries are already moving to taxation and regulation of the carbon market. In May, for example, the Zimbabwean government? said it plans to take up to half of the revenue from carbon credit sales. That could stifle investment, Kim said. Gold Standard suspended its issuance of credits from Zimbabwe after that decision.

The View From Gabon

Another area of focus for Ruto this week was mounting sovereign debt, which he said is a major obstacle to African countries’ climate ambitions. Gabon recently pioneered a promising strategy to address its sovereign debt, closing a deal with Bank of America in early August to clear $500 million in debt in exchange for stepping up marine conservation measures, the first such “debt-for-nature swap” in Africa. But the future of that deal was thrown into uncertainty last week following Gabon’s military coup.

Notable

- In addition to its carbon credit purchase, the UAE said it will channel $4.5 billion to clean energy projects in Africa. The money, mostly in the form of equity investments by the state-run renewable energy company Masdar, is part of a push by the UAE, ahead of its hosting of COP28, to put a more positive spin on its vast oil wealth.